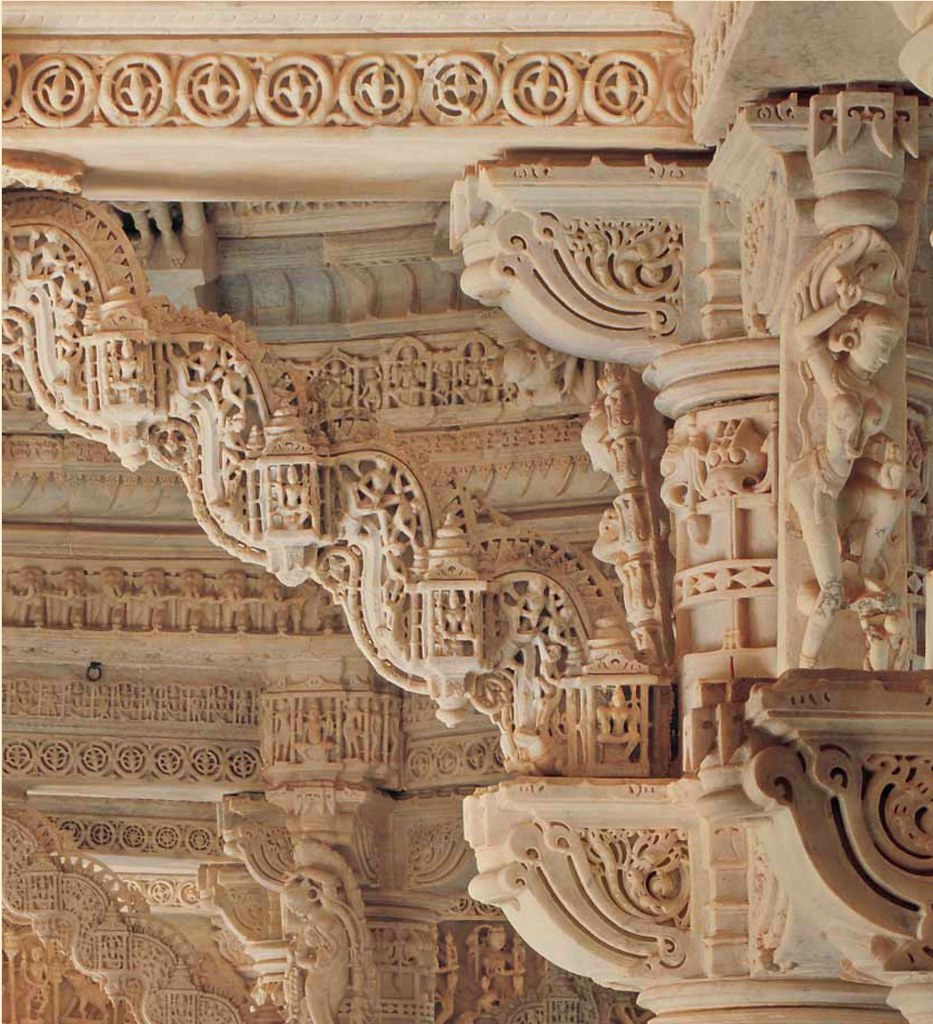

left side Vimala Vasahi Temple (1032 AD) on Mount Abu, Rajasthan, dedicated to Adinatha, with garlandlike, richly decorated arcs (makara toranas) free pending from the middle between two columns, carried by little pillars on each column.

left side Vimala Vasahi Temple (1032 AD) on Mount Abu, Rajasthan, dedicated to Adinatha, with garlandlike, richly decorated arcs (makara toranas) free pending from the middle between two columns, carried by little pillars on each column. right side

right side Vimala Vasahi Temple (1032 AD) on Mount Abu, Rajasthan,

dedicated to Adinatha, with garlandlike, richly decorated arcs (makara toranas) free pending from the middle between two columns, carried by little pillars on each column.

Social and religious conditions in 600 BC

The 6th century BC witnessed a spiritual and philosophical revival in India. This was comparable to the ferment in intellectual life in China (Confucius and Laotse), Persia (Zarasthura), Israel (Jesaja and Jeremiah) and Greece (Thales and Pythagoras).

Mahavira’s life of wandering mostly spent in Magadha (in the present-day state of Bihar). This is the same area where Gautama Buddha also preached. Undoubtedly, other than these two, there were many other ascetics and teachers preaching in this area, all of them rebelling against the existing social system. That reached its ultimate form shortly after the Aryan migration and settlement in the land had fossilised and become very rigid thereafter. The caste system was already in existence and the untouchables at the bottom subjected to all the inhumanities, arrogance and injustices due to such a system.

The exclusive leadership of the Brahmans dominated this system. The Brahmans believed they alone knew the will of the gods and sought to influence them with their exclusive rituals. They derived their authority from their knowledge of the Vedas, the oldest holy scriptures of India, and the performance of animal sacrifices. In the classic mould of heretics, both Mahavira and Buddha attacked privileged position of the established priestly class by questioning the authority of the Vedas. Denying the existence of a supreme god and forbidding the blood sacrifices. Perhaps this is the reason why so many kings were their patrons. After all, it would only lie in their interest to curtail the monopoly of the Brahmans.

The similarities between Mahavira and Buddha as regards the milieu, the geographical area, the time period as well as their goals, misled several people in the West till as late as the 19th century to believe that both religions were identical. At times, it considered that Buddha was the teacher and Mahavira the disciple; at other times, the reverse held to be true. The Jains themselves believe Buddhism to be a misleading and wrong doctrine founded by a Jain monk gone astray. Buddhakirti an ascetic ate a fish washed up by the current because he believed the fish no longer possessed a soul this is supposed to have led to a schism and the founding of Buddhism. According to another variation, a disciple of Parsvanath by the name of Maudgalyayana created Buddhaness by declaring the Buddha to be god because of the hatred and jealousy he harboured against Mahavira. Some European scholars held similar opinions, misled by the name of Mahavira’s disciple that was also Gautama. Hermann Jacobi successfully proved that Buddhism and Jainism were two different religions independent of each other.

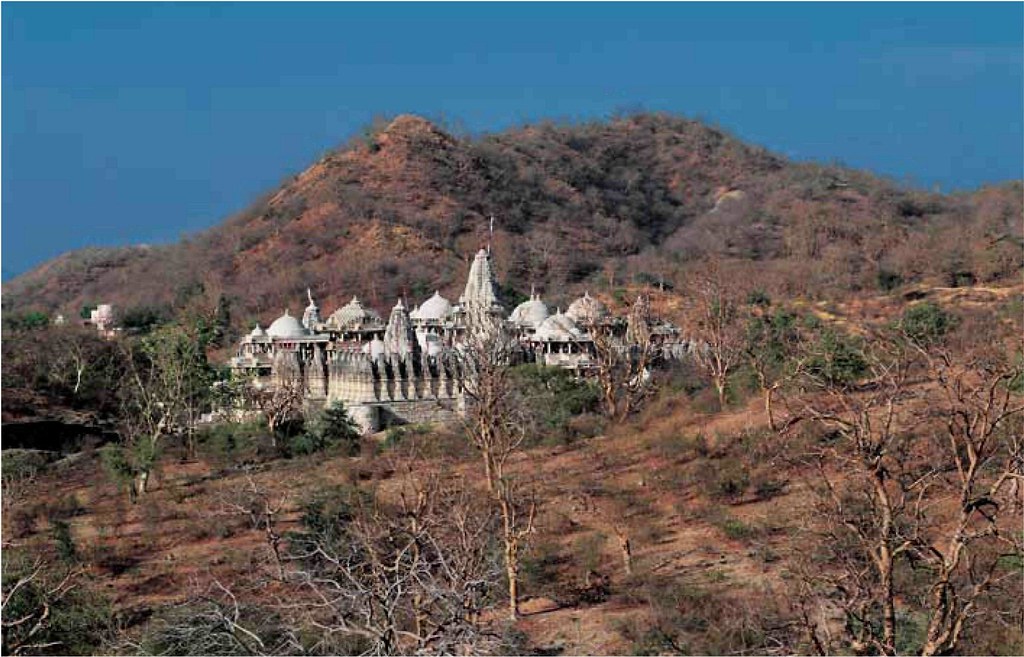

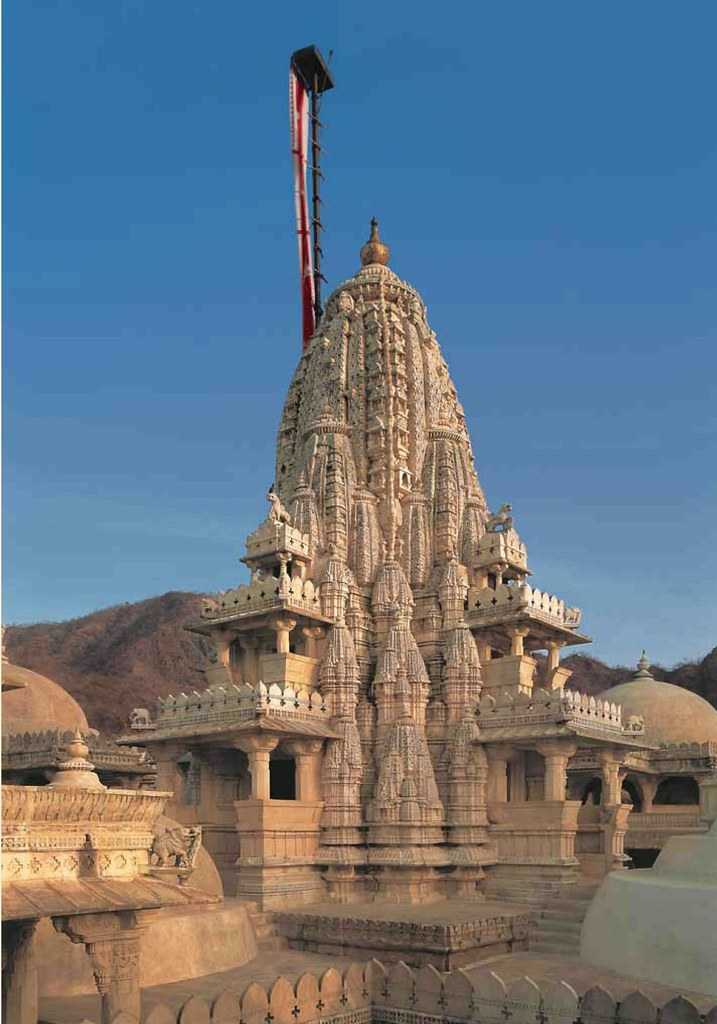

Mighty temple tower, Shikhara, in Dharna Vihara Jain temple, 1439 AD, Ranakpur, erected on sanctum with four-faced idol of Adinatha.

Mighty temple tower, Shikhara, in Dharna Vihara Jain temple, 1439 AD, Ranakpur, erected on sanctum with four-faced idol of Adinatha. Mighty temple tower, Shikhara, in Dharna Vihara Jain temple, 1439 AD, Ranakpur,

erected on sanctum with four-faced idol of Adinatha.

Antiquity Of The Jain Doctrine

In all probability, the doctrine preached by Mahavira was not entirely original. He merely improved upon an already existing edifice developed by Parsva and maybe others before him. This exemplified by the fact that Mahavira numbered as the 24th and last Tirthankara (i.e. ford maker) of the Jains, thus forming the pinnacle in a long chain of predecessors. At the time of his birth, Mahavira’s parents were already the followers of Parsva, the 23rd Tirthankara. Unlike the case of the Buddha, a tradition pre-existed Mahavira. Thus, Mahavira did not develop a new philosophical system, nor did he profess to have attained a new kind of revelation. Instead, he merely acquired supreme knowledge of what pre-existed known and practised, in part, by the community.

The stories of the long succession shrouded in mythology of Jain Tirthankaras. The Tirthankaras do not appear to belong to our temporal and spatial world since incredibly long life spans and enormous heights ascribed to them. This is due to the pessimistic worldview of the Jains according to which people of an earlier age were perfect in appearance and enjoyed longer lives, but in the course of time, with cosmic decline, the reverse happened. The extended time interval documented in these stories, from the time of the earliest Tirthankara until the present day, is supposed to substantiate the claim of the Jains that their religion is eternal.

This intended not to imply that the Tirthankaras did not exist. Three of them Rishabha (also called Adinatha, the first Tirthankara), Ajita and Arishtanemi were already known to the authors of the Yajurveda (dated around 1000 BC). In addition, some names, kinship relations and signs provide certain information of historic value. For example, the sign of bull represented Adinatha and it is indicative of bull worship, which, in ancient times, was widely prevalent all over the Orient.

The Hindus regard Bharata as the founder king of their country, after whom the country was named (in Hindi India is called Bharat). The Jains believe that Bharata was the son of Adinatha. This would imply that the Jain religion existed from the time of the earliest Indian mythology. The 22nd Tirthankara, Arishtanemi (whose name means outer rim of whose wheel is undamaged) mentioned in the legends as the first cousin of Lord Krishna. His name refers to the ‘sun wheel’ or the sun chariot and this suggests that he belonged to the quasi-mythical sun dynasty.

The majority of the Tirthankaras, however, are by no means of Aryan descent. This could mean that indigenous ideas of a negative philosophy for the first time began to counter the heroic, active and positive worldview of the Aryans.