Parsva

Only Parsva, the Tirthankara who immediately preceded Mahavira, appears to have been a historical personage. This is evident in the fact that his age of ‘merely’ one hundred years appears to be ‘reasonable’ as compared to that of his predecessors. Moreover, his mention in the biography of Mahavira; he is supposed to have lived two hundred and fifty years before Mahavira, in which case he must have lived in 800 BC. Several details mentioned in his biography corroborate the conditions of this period.

Although we are dealing with a period for which almost no reliable information on India is available, yet accounts of Parsva show a connection between him and the general trends in religion and philosophy, which were dominant during the second millennium and at the beginning of the first. These concepts held the whole of the Orient loosely together. Common to all these systems was the strict dualistic worldview of the eternal struggle between the forces of good (light) and those of evil (darkness); examples of this encountered in Egypt, in the Zoroaster’s of Persia and in the Judaeo-Christian tradition. In the mythology of the near east the same translates into the tales of two brothers, for example the war between Cain and Abel, Jacob and Isaac or between the two sets of estranged brothers or, Anubis and Bata or Horus and Seth.

Similarly, Parsva’s life and that of all his previous incarnations described as a war between him and an evil darker brother who personifies desire, the craving for power and a lust for life. We will touch upon this at greater length in a later chapter; what should, however, be noted is the fact that, in comparison to Mahavira, his predecessor Parsva appears to be more firmly rooted in the general ‘internationally’ accepted belief system than is the case with Mahavira.

Until the present day, Parsva is the most popular Tirthankara among the Jains. One reason for this could be the greater austerity of Mahavira and his insistence on increased asceticism. Another reason for Parsva’s greater popularity could be the fact that his name is associated with snake worship, which has an immense following all over India. The impressive art at Ranakpur justify this statement. The four vows preached by Parsva have endured: a true Jain should refrain from injuring living beings, should not utter a falsehood, should not acquire anything that not given to him, and should not own property. At the end of Parsva’s life, his lay followers are said to have numbered 1, 64,000 men and 3, 27,000 women. In addition, 16,000 monks and 38,000 nuns took the vows. Even if these figures are an exaggeration, the predominance of women could be indicative of the fact that Jainism not only opposed the caste system but also promised women a better position in life.

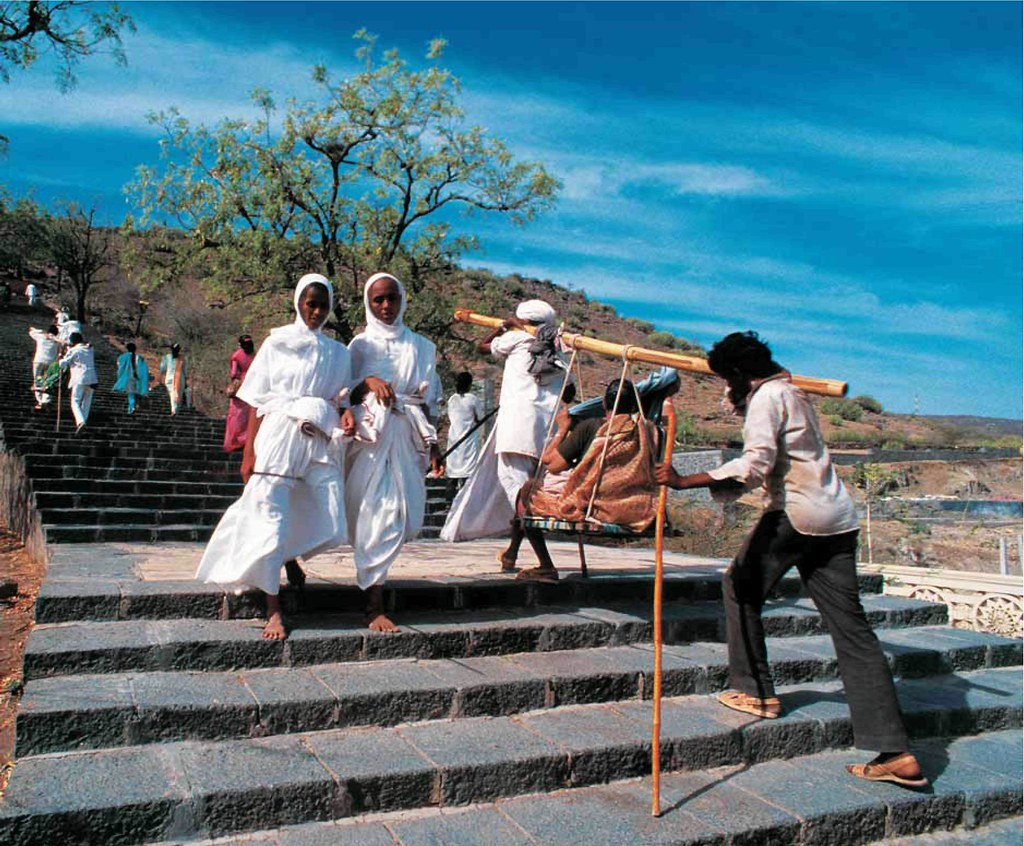

about 3500 steps !

about 3500 steps !In the book the following subjects are elaborated:

JAIN PHILOSOPHY AND RELIGION AND THE CONCEPT OF SOUL

The concept of god

The souls or animate substances

The inanimate substances

Karma

The pessimistic worldview of life and the material world

Liberation or moksha

The universe

The completed souls

A BRIEF HISTORY OF JAINISM

A brief definition

Shvetambaras and Digambaras Ajivikas

Canon

Bhadrabahu and the expansion of Jainism to the south

The spread of Jainism to eastern and western India

Deepening of the schism between the Shvetambaras and Digambaras

A further history of the Digambaras

Further details on the history of the Shvetambaras

The Sthanakavasi

Renaissance

THE PRESENT DAY COMMUNITY OF THE JAINS

The Sangha

Monks and nuns

The lay followers

Rituals accompanying life

RITUAL AND TEMPLE WORSHIP

TheTirthankaras

Other Deities

The Temple Ritual

Festivals and Special Days

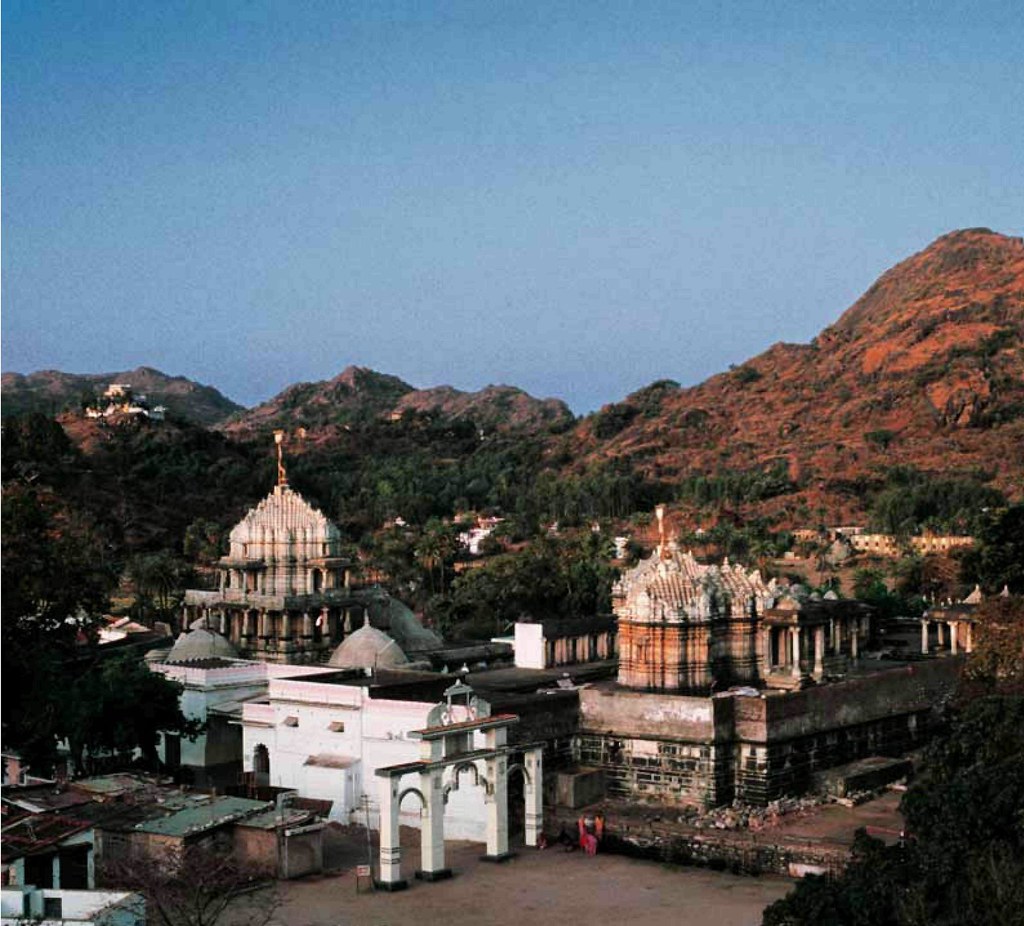

Pilgrimages