History and Doctrine of Kanji Swami Panth

1. History

The Kanji Swami Panth is the most successful Jain movement in the present century, and Kanji Swami has been the reviver of Digambara Jainism in Gujarat and all India.

Kanji Swami was born in 1889 in a village on the Kathiawar Peninsula of Gujarat. His family were Sthanakvasis, but he was orphaned when he was young. He searched for a teacher, taking initiation in 1913 as a Sthanakvasi monk. During the initiation celebration he rode on an elephant and tore his robe, an inauspicious event. Soon he became a learned monk, well-known as the 'Koh-i-noor of Kathiawar.' About 1921 he encountered Kundakunda's Essence of the Doctrine which changed his life. Studying more Digambara texts he gradually moved towards Digambara Jainism and in 1934 at Songadh near Mount Satrunjaya during Mahavir Jayanti, the festival on Mahavira's birthday, he proclaimed himself a Digambara layman. This produced a violent reaction from the Sthanakvasi community and he sheltered in 'The Star of India,' an ex-British house owned by a follower.

Though he lived a celibate life, Kanji Swami never took Digambara ascetic initiation even when there was a revival of Digambara monasticism. In the tradition of Banarsidass, the first important layman in Jain history (he built libraries and temples and sponsored large-scale pilgrimages), Kanji Swami's sect was primarily a lay movement.

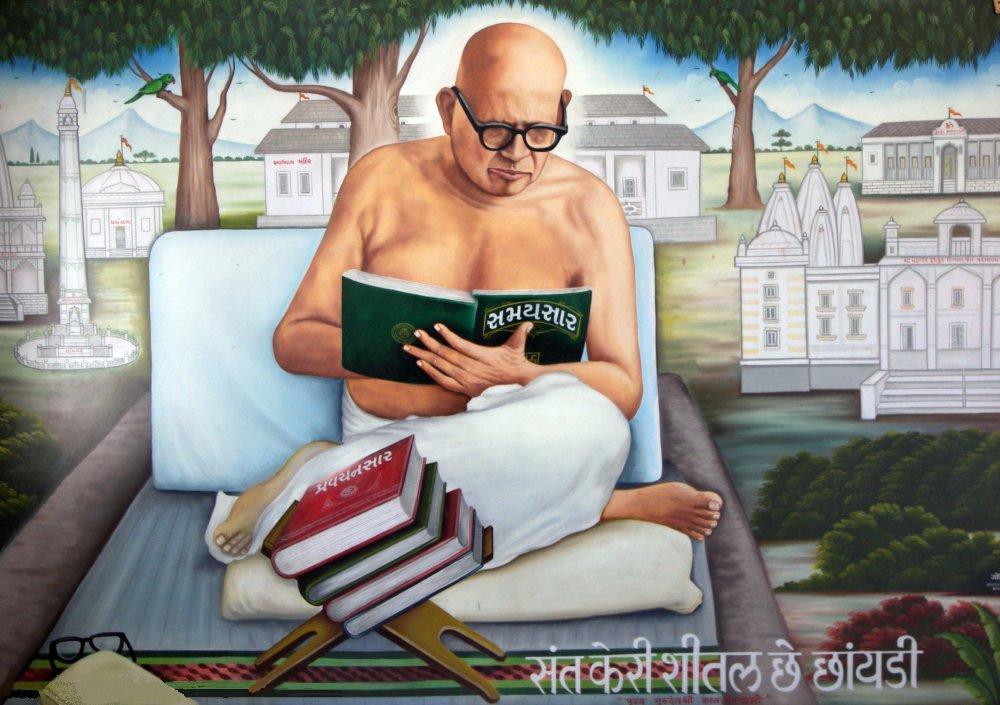

Kanji Swami studying Kundakunda's work "Samayasara"

In 1937 the Digambara Svadhyaya Mandir ("Study Temple") was built by Kanji Swami's devotees at Songadh, and this was followed by a building programme that continues today. This is now a complex of massive marble buildings near Mount Satrunjaya. Kanji Swami made a pilgrimage by car to Digambara holy places all over India and consecrated a large number of temples and images, and even travelled to Mombasa. He died in 1980.

The current head of the Kanji Swami Panth is Campabahen Mataji, the only woman to lead a Jain sect. Born in 1924 in Gujarat, as a child she followed Kanji Swami when he was a Sthanakvasi monk. At the age of eight she claimed full experience of her soul and memory of previous lives, one being with Kanji Swami in Mahavideha listening to Simandhara teaching to Kundakunda. To prove this she described Simandhara's samavasarana, an assembly hall for preaching.

The Kanji Swami Panth has a board of trustees with a president elected every five years, who administer large financial resources. The Panth is a missionary movement and is also involved in extensive publishing and educational projects, training preachers and running a network of schools.

Paul Dundas, in his book The Jains (London 1992, p. 231f.) feels that despite criticism of the Kanji Swami Panth by Gujarati Shvetambaras, especially about the claim for Kanji Swami's next birth,

"...it is difficult to avoid the conclusion that a substantial part of the future of Jainism may well lie with the Kanji Swami Panth, at least outside India." This is because "the Panth, with their emphasis on direct contact with an ancient scriptural tradition, skilful promulgation of a myth of origin, scaling down of ritual requirements, rejection of the ascetic lineage system, and advocacy of a direct, 'do-it-yourself' form of Jainism based on texts which translation has made accessible to all, would seem to be well suited to the Jain community in Africa and the west, which has largely lost contact with the ascetic interpretation of the religion".

2. Doctrine

Though trained as a Sthanakvasi monk, Kanji Swami turned to Digambara Jainism and the mainstream Digambara mystical tradition centred on Kundakunda became the basis of the doctrine of his sect. But just as Kanji Swami's life was not exclusively Digambara, so Kundakunda's mystical doctrine was not exclusively Digambara since he drew on Jain ideas which existed before the sectarian schism.

Kanji Swami did not write any books. His discourses, however, were mostly taped. He did not claim to be saying anything new, only going over the words of Mahavira and Kundakunda. A typical discourse was a running commentary on the writings of Kundakunda, a practice still carried out by the sect. Kanji Swami believed Kundakunda's Essence of the Doctrine to be the essence of Jain teachings. This work is the most well-known of the second or third century CE mystic and is concerned with the real nature of the soul. The soul is a naya, standpoint, that is either nishcaya, certain, paramartha, supreme, or shuddha, pure, and is a pivot by which other entities, beliefs, and practices can be judged. The soul cannot be changed by contact with karmic matter and stands as the only object of omniscience, everything else being transient and worldly. The spiritual path should therefore be one of inner experience. Srimad Rajacandra was another influence (see: History and Doctrine of Kavi Panth).

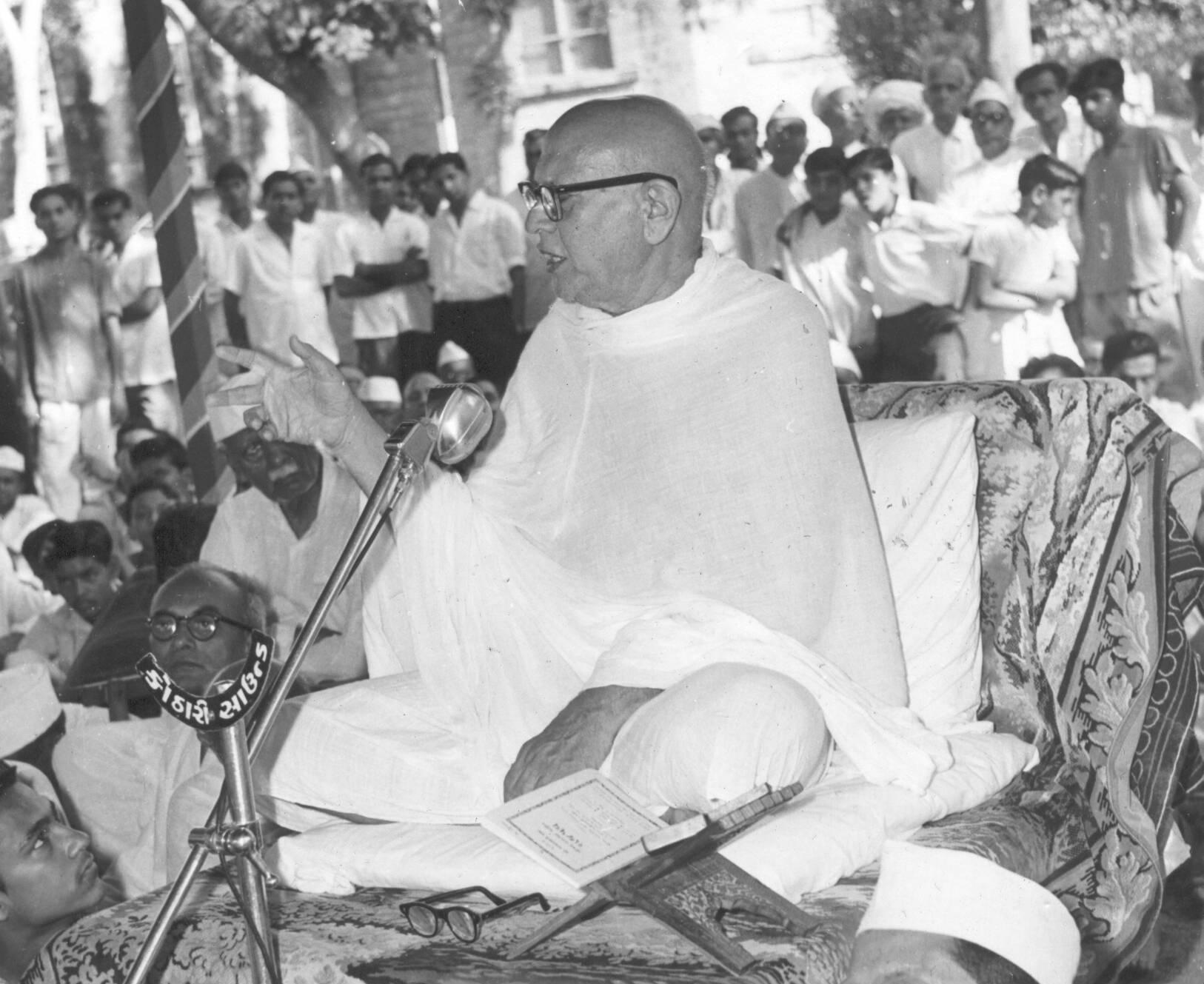

Kanji Swami instructing his adherents

Mundane doctrine such as diet was ignored by Kanji Swami, as all Jains would know this. His emphasis on nishcaya naya, the higher level of truth, over vyavahara naya, ordinary life, surpassed even Kundakunda. Ritual and merit-making activities are largely irrelevant because they are linked to the passions. The practice of austerities and meditation cannot affect the soul, and polarities such as good and bad, fasting and non-fasting, are significant only at the worldly level in the realm of transmigration. Kundakunda saw ritual as only being valid if directed to the soul. Kanji Swami did not reject Jina-images and even consecrated many of them. The Three Jewels of right faith, knowledge, and practice needed experience of the soul to function correctly. Spiritual deliverance could only come with a pure soul.

The Kanji Swami Panth has always been a lay movement and ascetics have no special status. Kanji Swami has said that to him ascetics personify the fundamental principles of Jainism. Kundakunda also saw ascetic practice as preventing and destroying karma and thus leading to self-knowledge and the soul. In the Kanji Swami Panth are about sixty brahmacaris, lower-order ascetics, who are mostly women that took vows from Kanji Swami. Though celibate, they are allowed to travel and own property.

Lacking a place in any Digambara ascetic lineage descending from Kundakunda, Kanji Swami validated his teaching authority by claiming in a previous life in Mahavideha (in Jain cosmography this is at the centre of the island of Jambudvipa) to have been present when Kundakunda visited to listen to the Jina Simandhara. This linking of Kanji Swami with this legendary event was told to him by a female disciple, Campabahen Mataji, who said she had been there too hearing Simandhara expound the true doctrine to Kundakunda. After this Kundakunda wrote his Essence of the Doctrine. Campabahen claimed after Kanji Swami's death that he would be reborn as Jina Suryakirti in the continent of Dhatakikhanda.

3. Symbols

Kundakunda is symbolised in the Digambara Svadhyaya Mandir, the main temple of the sect, with the words of his five main treatises engraved on the walls and covered in gold leaf. Another marble building at Songadh is an elaborate reconstruction of Simandhara's samavasarana as described by Campabahen.

Puja, ritual worship, for the sect is of a simpler nature than with other image-worshipping sects. It involves darshan, seeing, and anointing the image with water only.

'The Star of India' house in Songadh where Kanji Swami took refuge when he declared himself a Digambara layman, is considered the birthplace of the Kanji Swami Panth. Followers come there for bhavapuja, mental worship, each year on Kanji Swami's birthday.

4. Adherents

The Kanji Swami Panth claim an extremely large following throughout India. Followers are often Digambaras or Sthanakvasis in origin. In Songadh itself the three hundred families who were originally Sthanakvasis now follow the Kanji Swami Panth. In Gujarat there are many converts from the low Jain caste of the Halari Oswals. There is a large following outside India in Africa, especially Kenya, and in the West.

5. Main Centre

Songadh, Kathiawar, India.