15. वस्तसाम्यु ेणचत्तबदाते तमोणव्बि्य ऩन्था्॥१५॥

vastusāmye citta-bhedāt-tayorvibhaktaḥ panthāḥ ||15||

The object being the same, perception and desire vary according to the various minds.

16. तदुऩयागाऩ त्वाते णचत्तस्य् वस्त ु ाता ातभ ॥१६॥्[3]

tad-uparāga-apekṣitvāt cittasya vastu-jñātājñātaṁ ||16||

Things are known or unknown to the mind, being de-pendent on the colouring which they give to the mind.

17. सदा ाताणित्तवत्तमस्तत्प्रबो्ृ ऩुषस्याऩणयिाणभत्वात ॥१७॥्

sadājñātāḥ citta-vrttayaḥ tat-prabhoḥ puruṣasya-apariṇāmitvāt ||17||

The states of the mind are always known because the lord of the mind is unchangeable.

The whole gist of this theory is that the universe is both mental and material. And both the mental and material worlds are in a continuous state of flux. What is this book?

It is a combination of molecules in constant change. One lot is going out, and another coming in; it is a whirlpool, but what makes the unity? What makes it the same book? The changes are rhythmical; in harmonious order they are sending impressions to my mind, and these pieced together make a continuous picture, although they parts are continuously changing. Mind itself is continuously changing. The mind and body are like two layers in the same substance, moving at different rates of speed. Relatively, one being slower and the other quicker, we can distinguish between the two motions. For instance, a train is moving, and another carriage is moving slowly alongside it. It is possible to find the motion of both these, to a certain extent. But still something else is necessary. Motion can only be perceived when there is something else which is not moving. But when two or three things are relatively moving, we first perceive the motion of the faster one, and then that of the slower ones. How is the mind to perceive? It is also in a flux. Therefore another thing is necessary which moves more slowly, then you must get to something in which the motion is still slower, and so on, and you will find no end. Therefore logic compels you to stop somewhere. You must complete the series by knowing something which never changes. Behind this never ending chain of motion is the Purusa, the changeless, the colourless, the pure. All these impressions are merely reflected upon it, as rays of light from a camera are reflected upon a white sheet, painting hundreds of pictures on it, without in any way tarnishing the sheet.

18. न तत स्वाबासंदृश्मत्वात ॥१८॥्

na tat-svābhāsaṁ dṛśyatvāt ||18||

Mind is not self-luminous, being an object.

Tremendous power is manifested everywhere in nature, but yet something tells us that it is not self-luminous, not essentially intelligent. The Purusa alone is self-luminous, and gives its light to everything. It is its power that is percolating through all matter and force.

19. एकसभम ेचोबमानवधायिभ ॥१९॥्

eka samaye c-obhaya-an-avadhāraṇam ||19||

From its being unable to cognise two things at the same time.

If the mind were self-luminous it would be able to cognise everything at the same time, which it cannot. If you pay deep attention to one thing you lose another. If the mind were self-luminous there would be no limit to the impressions it could receive. The Purusa can cognise all in one moment; therefore the Purusa is self-luminous, and the mind is not.

Swami Vivekananda does not comment on the sutra which is 16th sutra in most versions of Patanjali Yoga Sutra.

This sutra is:

16. न चैकचित्ततन्त्रं चेद्वस्तु तदप्रमाणकं तदा किं स्यात् ॥१६॥

na caika-citta-tantraṁ cedvastu tad-apramāṇakaṁ tadā kiṁ syāt ||16||

“An object exists independent of its cognizance by any one consciousness. What happens to it when that consciousness is not there to perceive it?”

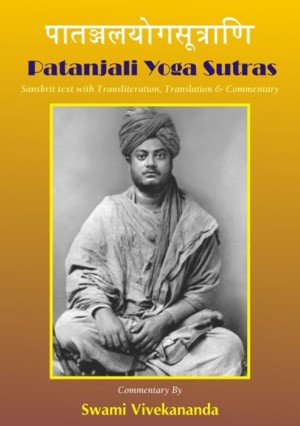

Swami Vivekananda

Swami Vivekananda