The Mark of Nonviolent Behaviour

I was initiated into the order of Jain asceticism by my most revered guru (preceptor) Kalugani. The first mahavrata (the great vow) observed by the Jain monks happens to be that of ahimsa (nonviolence) and the fifth one is that of aparigraha (non-possession or non-acquisitiveness). The main objective of this prime lesson was to expose me to the onerous course of ascetic life. He alerted me to my newly adopted role where conscientiousness would determine my behaviour and where there was no room for spiritual lethargy or indolence. He exhorted me to remain ever alert and careful. Not even one step betraying casualness or moral indifference could be allowed in ascetic discipline:

“Move not a step in abandon, lest an insect should be trodden by your feet. You have to examine each word that you utter, lest it should offend an individual. While you eat your meal, be careful lest you should trespass on another’s claim. Restraint will mark your life ever and anon else you will attempt to monopolise any material object to the detriment of others. You cannot take a cavelier attitude to anything nor can you hurt another’s feelings. Nobody has a right to command anybody or to hold him in bondage.”

This was the opening lesson in nonviolence and goodwill that my preceptor, the revered Kalugani, was pleased to impart to me. He was able to inculate in me a flair for teaching. Not for a moment did my faith in nonviolence erode since that significant initiation.

A Rich HeritageDuring the week following my initiation into monkhood I began the study of the Dashvaikalika Sutra, an important Jain sacred text. Here I learnt, “Be careful while you move, stand, sit at a place, sleep, eat and speak.” With this unexceptionable and masterly exposition of spiritual alertness (apramad) in each action, I was taught never to take liberty with any objects. Unless so warranted no order of things was to be disturbed or a grain of anything to be wasted. He who chooses the path of restraint and abstinence will not even think of misusing anything on the planet earth.

The third lesson taught to me was that each individual has a right to free and independent existence. Its corollary is that you have no right to cause injury or discomfort to any living being. If one teases, hurts, displeases or subjugates the other, it is an unforgivable act of violence.

The Genesis of NonviolenceIt was not a mere dogma that I learnt from my master, the great Kalugani, but my constant exposure to his nonviolent lifestyle rooted in the purity of actions imparted to me a deep orientation in these universal truths that stood the test of the closest scrutiny. He never criticized or censored what others did. A rich heritage had been bequeathed to him. This tradition of stoicism and catholicity is as ancient as Lord Mahavira himself. During his life, Ardakumar thus spoke to Gaushalak, the sectarian head of the Ajivakas:

“I denounce not an individual: I only denounce a dogma that merits denunciation.”

Acharya Bhikshu, the founder of the Terapanth Jain sect, had embraced this principle implicitly. He abstained from adversely commenting on any sect or individual. My venerable master Kalugani strictly followed this noble path. He instructed one and all never to show disrespect during scriptural debates. To him “agitated behaviour during the debate is a sure sign of defeat. A debate that degenerates into verbal heat is synonymous with violence.”

My master’s composure and stoicism left an indelible impression on my psyche. What he preached, he scruplously practised himself. Consistency in word and deed is the positive indication of ahimsa. To a practitioner of nonviolence uttering unpleasant words is an anathema, what to say of deprecating another being. This lesson sowed in me the seeds of equanimity and restraint which became my natural traits.

Instruction in FearlessnessNonviolence and truth are synonymous. The two are a sine qua non for each other. The quintessence of his kind lesson may be expressed thus:

“Never be a coward. Fear neither age or disease. Conquer greed and do not fear death. Chimeras frighten one who is chicken-hearted. A timid person is a hostage to apprehensions. Such an unfortunate being is shorn of austerity and asceticism.”

My preceptor’s teaching made me realize that nonviolence and truth are embedded in fearlessness. In fact, nonviolence and truth are concomitants of each other.

A man given to acquisitiveness and avarice never attains fearlessness. It follows that nonviolence can never exist in such a set of circumstances. Fear is the prime mover of violence. To frighten and intimidate the other is nothing but violence and so is one’s affliction with fear and apprehension. It means that you should never be frightened, nor frighten others. This is the mutually co-existing principle of subjective and objective fearlessness. Non-avariciousness is significant in as much as fearlessness is its corollary. Falling for the material objects leads to anxiety and craving for it leads to violence. We fear death because we are deeply attached to our physical frame. This attachment to the gross is another name for acquisitiveness.

Violence and parigraha (acquisitiveness) are inseparably welded together. Conversely, nonviolence and non-acquisitiveness are wedded together. I owe the debt of gratitude for these golden truths to my preceptor, my most revered master.

Nonviolence owes its origin to fearlessness, and stoicism is a shield that protects it. The most revered Kalugani had the two innate attributes reflected in his own conduct. His grip on both these virtues was impeccable. I emulated his exemplary life and was able to imbibe the spirit of these cardinal values naturally into my nature.

It was the era of Maharaja Ganga Singh in the erstwhile state of Bikaner. He was counted amongst the ablest, strongest and illustrious rulers. The venerable Kalugani used to spend the four months of monsoon at Sujangarh. Maharaja Ganga Singh was impelled by some divine power to call on the saint there. He came to the place where Kalugani was delivering his discourse but he refrained from entering the precincts of the building. He simply paid obeisance to the Acharya with folded hands from outside. However, he failed to catch the eye of the revered Kalugani. The devout house-holders who witnessed the spectacle were mighty scared. Such was the terror of the ruler.While Maharaja bowed to the saint the latter was not looking at the door. Since the Acharya didn’t raise his hand to bless the ruler when he bowed in reverance, everyone present in the congregation was struck with terror. No one knew the way to pacify the ruler’s wrath. Mantri Muni Magava Guni and some eminent shravaks deliberated on the ‘disaster’ and kept awake till mid-night. My revered Master had however retired as usual for rest with no line of anxiety on his forehead. His simple observation was,

“Why be vexed? It happened only inadvertently. I never meant to slight anybody. How could I be indicted for something far away from my thought?”

This imperturbability was his characteristic at every juncture.

Triumph of Stoicism

Once he was camping at Bikaner for his chaturmas (four months of rainy season when Jain monks stay at a place). The followers of another Jain sect chose to oppose his presence with all vigor and belligerency at their command, just short of assault and battery. Verbal invectives knew no bounds. Fracas led my master to summon all the monks and nuns. He exhorted them to remain calm and unruffled despite provocative situation. He asked them not to react and remain indifferent to what was happening. They should display utmost restraint and stick to their work.

One of the monks could not contain himself and remonstrated. On learning of this lapse on the part of a monk of his order the Acharya prescribed for him austere penitence which was a source of inspiration to other monks to be ever composed. Stoicism triumphed over aggressiveness.

Provocation was defeated by stoicism and peace prevailed. This lesson in tolerance struck a deep note in my person and created in me enough strength to cope with a similar occurrence at Bikaner at a later date which posed a threat to us.

Averting a Catastrophe

The incident dates back to the year 1937, a year or so after my installation as the ninth Acharya of the Terapanth Jain sect. My monsoon stay (chaturmas) at Bikaner had come to an end. As is the practice in the Jain tradition at the end of chaturmas, the Jain Acharyas or monks must leave for another town in a procession. It often consists of thousands of people. A huge procession led by me, followed by monks, nuns and shravaks (votaries) began as scheduled. As we emerged on the main road we were confronted with a similar mammoth procession of a rival sect led by its Acharya. Rangda Chowk was the bottleneck where the two processions converged for the likely showdown. The crowds were amurmur as to who should eat a humble pie and give way to the other group. The rival procession was brimming with excitement. It was clear that they would not give way to us.

Our group was also in no mood to give in. I heard them blurting, “Why should we budge for them? Do they take us to be cowards?” Ishwarchand Chopra, a prominent citizen, remonstrated at the idea of conceding to the opponent. I collected my wits and chose to turn towards Rangda Chowk, another direction rather than inflame the situation. Each one followed me and a likely collision was averted.

Later Maharaja Ganga Singh was briefed of this incident. His observation was, “Acharya Tulsi may be younger in age but his actions are pregnant with wisdom. He has added to the glory of Bikaner. Had he chosen to confront the rival group, the catastrophe was certain with stampede and causalities.”

At such critical moments of my life the saintly image of my Guru revered Kalugani who was an embodiment of stoic endurance flashed in my mind and helped me to take a right step. There was many an occasion in my career when I drew strength from his teachings. The training in ahimsa imparted to me by him through precepts and models of nonviolent behaviour stood me in good stead.

The Stoic Smiles in the Face of Fire and Brimstone

Once I wrote: “There might be some people who may oppose us but we should take their opposition as a source of amusement.” To stay nonchalant in the face of an aggressive situation is the mark of equanimity. It is an example of the nonviolent conduct of the highest order. I came across an event of this kind while we were in Malva (a part of the present state of Madhya Pradesh). The revered Kalugani was trekking Jawara and Ratlam. His padyatra (journey on foot) provided me with a series of practical lessons in ahimsa. There a rival Jain sect created an aggressive situation by pasting each wall with virulently slanderous pamphlets against the principles of ahimsa as believed by the ascetics and shravaks of the Terapanth Jain sect. The entire town was aflame with sectarian tension.

Acharya Kalugani endeavoured to assuage the mass feelings and justify the doctrine of giving charity or alms and showing compassion (daan and daya) as interpreted by the Terapanth Sect. However, he scrupulously abstained from a counter-offensive. He demonstrated stoicism par excellence. A Jain pandit from Ratlam told him that he had been impassively observing the events and was impressed by the way he (the Acharya) had handled a potentially explosive situation. Undoubtedly he betrayed a profound discerning wisdom that shuns all recourse to confrontation. The entire provocative situation was dealt with nonchalantly. Such wisdom dawns only on a pious soul that has cultivated a nonviolent mode of behaviour.

I treat it as a reward of my prolonged and serious contemplation.

Acharya Kalugani replied to the pandit (Jain scholar): “Esteemed gentleman, a stoic person endowed with steadfast wisdom alone can withstand the aggressive situation created by another one with a weak moral fiber who is prone to react instantaneously with a similar squib.”

These instances of the life of a great soul brought home to me the need for composure and stoicism in the face of provocation.

The Shield of Nonviolence

Stoicism is the shield of nonviolence. Ahimsa (nonviolence) or universal goodwill cannot fructify in its absence. The revered Kalugani’s life was an illustration of nonviolence and stoicism. When he entered the evening of this great career he developed a carbuncle in his left index finger. The pain was excruciating, but his prescribed travelling schedule was followed rigorously. He chose to abstain from surgical measures with the instruments at hand brought by the surgeon. He could discern the grain from the chaff, the subtle from the gross. He decided to stick to the ascetic tradition of neglecting the body. It was an agony that lasted over two months. To watch his stoic indifference to the agonizing pain then was a unique training in forbearance and ahimsa for me.

A nonviolent soul has to guard against the temptation of comfort which could mean lapsing into laxity. Vigilance and non-attachment alone may instill in us the qualities of stoicism and equanimity. Consciously or unconsciously I imbibed the guiding ethical principles that permeated the life and conduct of my great Master. These seeds of ahimsa and goodwill for all and sundry sprouted in the terrain of my life. These lessons in enlightenment shaped the contours of my conduct time and again as and when the need arose. I may cite one instance of such an occasion of trepidation.

I had authored a book titled agnipariksha (literally: the fire test). It is in the form of a long narrative poem. It narrates how Sita was subjected to fire-ordeal to prove that she was chaste. I was having my chaturmas at Churu then. Everything was going on harmoniously. Some fanatics thought it to be a good opportunity to malign me. They spread the rumour that Acharya Tulsi (myself) has composed some stanzas in the poem which cast aspersions on Sita’s character. They fomented communal tension and roused the mass frenzy against me. Their accusation was a blatant lie. Agnipariksa was composed to highlight Sita’s lofty character but who reads the book? The people are carried away by rumour-mongering. All attempts were made to pacify their misgivings. Violent demonstrations against me became a daily ritual. Notwithstanding Madhya Pradesh High Court’s judgment that the work was innocuous, we chose to withdraw the book from circulation. This nonviolent action disarmed the agitators. Most respected Sarvodaya leader Jayaprakash Narayan declared it a great experiment in nonviolence. This decision was widely lauded, but a prominent author adversely commented and accused me of being unfair to the literary world. I attempted to alleviate his bruised feelings:

“I am a practitioner of nonviolence. My claim to authorship comes later. To acquit nonviolence honorably our conduct ought to be above board and exemplary. This is the motto of my life. My faith in it is unshakeable and steadfast and I expect the entire humanity to embrace this ethical norm to prevent violence and conflict.”

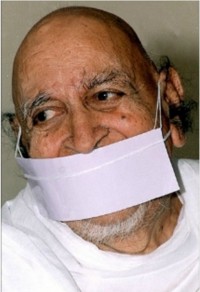

H.H. Acharya Tulsi was the ninth Acharya of the Jain Swetamber Terapanth sect. He shot into prominence because he launched Anuvrat Movement, a movement that aimed at rejuvenating moral and spiritual values in society. It was shorn of narrow sectarian bounds. He had many singular achievements to his credit, but prominent among them are his international crusade against violence, communal hatred and religious fundamentalism. On account of his contribution to human values he emerged as a national saint and was conferred the prestigious National Integration Award by the then Indian Prime Minister Narsimha Rao.

Acharya Tulsi

Acharya Tulsi