National Symposium on Jain Philosophy, Science And Scriptures

The Law of Karma and Free Will

Introduction

The karma doctrine has features that have a vital bearing on the question of free will and puruṣārtha.According to the karma doctrine, the fruition of the old karma attached to the soul by the past deeds results in new deeds which, in turn, bind the new karma and the cycle continues. Though this statement about the fruition of karma is true, it tells the partial truth, not the complete truth. The incomplete truth gave rise to the notion that a man is a prisoner of his past deeds; he has no control over his present deeds.[1] Such a notion raised several issues concerning moral responsibility of human beings and their liberation from the cycle of rebirth. If the present deeds of a person are fully controlled by his past deeds, then he would not be morally responsible for his deeds and would not deserve retribution for them.[2] Moreover, he would not be able to achieve liberation (mokṣa) as he has no control over his present deeds.

The doctrine of free will presupposes that human beings are free to determine the aims of their life and are capable to make an effort to fulfill them. In Jainism the issue of free will is resolved by invoking anekāntvāda. According to anekāntvāda human conduct is controlled by five factors, namely, time (kāla), nature (svabhāva), past karma (pūrva-karma), destiny (niyati) and human effort (puruṣārtha). These five factors are called ‘panca samavāya’.[3] It may be mentioned that Acharya Mahaprajna[4] interpretation of niyati is different than the commonly accepted interpretation. According to him, an occurrence based on universal laws is niyati. For example, one such universal law is that every living being, who takes birth, meets death; hence death is a niyati. Though anekāntvāda offers justification for rejecting the notion that the puruṣārtha is fully controlled by pūrva-karma, it does not explain why this notion is not corroborated by the karma doctrine.

The ‘panca samavāya’ also can be analyzed from a different view point. A human being has no control over kāla, svabhāva, and niyati. Though he has no control over pūrva-karma also, he can control the karma phala by puruṣārtha, as explained later. Hence pūrva-karma and puruṣārtha play roles in controllingfree will. Their respective roles in controlling free will can be explained by analyzing the characteristics of the law of karma.

Puruṣārtha

The precise definitions of the terms deed and puruṣārtha will be useful in the analysis of the causal connection between the law of karma and puruṣārtha. A deed is defined as an intentional, voluntary activity carried out by the physical action of mind, speech, and body, termed yoga and the spiritual action that includes intention, motivation, desire, etc, termed moha. In short, a deed is an activity performed by yoga-plus-moha.The term puruṣārtha has several meanings. Puruṣārtha in common parlanceis considered as human efforts to achieve specified aims in life. But puruṣārtha has a broader meaning in the context of the karma doctrine. All deeds are considered to be purposive in character as they are willed to attain certain goals. This characterization of deeds implies that all present deeds are puruṣārtha. Acharya Mahaprjna has given a similar definition of puruṣārtha.[5] According to him the present deeds are puruṣārtha and past deeds are karma.

We perform puruṣārtha all the time in our life. We do puruṣārtha of performing activities, which include selection of entities, for satisfying certain goals. For example, we do puruṣārtha of eating after selecting foods to stay alive, puruṣārtha of wearing after selecting clothes to protect our body, puruṣārtha of earning livelihood after selecting a profession to survive, and so on. In these examples, food, clothes, profession, etc. are the entities; eating, wearing, earning livelihood, etc, are the activities; and staying alive, protecting the body, survival, etc. are the goals. We experience the effects of the consequences of others’ deeds by performing the puruṣārtha of analyzing their deeds. For example, the members of a family feel miserable at the loss of wealth in a business venture by the head of the family when they do the puruṣārtha of analyzing his deed of business. Here the loss of wealth is the entity; analyzing his deed is the activity; and experiencing the effects of the consequences of his deed is the goal. We experience the effects of the consequences of natural events by performing the puruṣārtha of analyzing the natural events. In this instance, the effects of natural events are the entities; analyzing the events is the activity; and experiencing the effects of the consequences of natural events is the goal. All these examples of puruṣārtha indicate two causes of puruṣārtha: one, an entity such as food, cloth, profession, consequences of others’ deeds or natural events, etc; and second, yoga-plus-moha to perform the activity using the entity.

Every puruṣārtha has consequences and causes, but all consequences and causes of puruṣārtha are not controlled by the law of karma. The rules to determine the law-of-karma-governed consequences and causes of puruṣārtha are not discussed in the scriptures. Due to the lacking of such rules different interpretations of the law of karma were expounded, which led to controversies. An attempt to formulate the rules and to explain the role of puruṣārtha based on the rules is made in the paper by analyzing the characteristics of the law of karma and the nature of karma and karma phala.

Before proceeding further a few words about the terminology used in the paper are in order, as the terms karma and karma phala in Jainism have different connotations. Karma means deed as well as a type of extremely subtle matter (pudgala)that is bound to the soul and serves as a carrier of certain consequences of deeds to be defined later. Both types of karma have consequences and both types of consequences are called karma phala. Such terminology is a source of confusion which can be easily avoided by using discrete words for discrete meanings. In this paper karma is used only for the subtle matter, not for deeds and karma phala is used only for the consequences of karma, not for the consequences of deeds. The proposed terminology may not be appealing in the beginning, but it would be helpful in the end.

Characteristics Of The Law Of Karma

For the law of karma to be meaningful, it should be valid everywhere and all the time. The law of karma will become meaningless if it is applicable at some places and not the other places. For example, if it assumed that the law of karma is applicable only in India and not in other countries, then a person can make the law of karma meaningless by performing desirable puruṣārtha in India and undesirable puruṣārtha in other countries. Similarly, the law of karma will become meaningless if it is not applicable all the time. For example, if it is assumed that the law of karma is applicable only in the first half of the week and not the second half of the week, then a person again can make the law of karma meaningless by doing desirable puruṣārtha in the first half of the week and undesirable puruṣārtha in the second half of the week. It means the law of karma, similar to the law of gravity, is a universal law, as it is valid everywhere and all the time.

If the law of karma is universal, then the laws that govern the relationship between puruṣārtha and its consequences should be universal. Therefore, the consequences of a puruṣārtha should depend only on the puruṣārtha, not the time and place of the puruṣārtha. The law-of-karma-governed consequences of a puruṣārtha, whether performed in India or in the US, or somewhere else in the universe, should be identical. Likewise, the law-of-karma-governed consequences of a puruṣārtha that was performed in the past, or is being performed now, or will be performed in the future have to be identical. It implies that the consequences of a puruṣārtha that change with time and place of the puruṣārtha are not governed by the law of karma.

There are, therefore, two types of consequences of puruṣārtha. The consequences that do not change with time and place of puruṣārtha are termed invisible consequences; the universal, invisible consequences are governed by the law of karma. The consequences that change with time and place of puruṣārtha are termed visible consequences; the non-universal, visible consequences of puruṣārtha are not governed by the law of karma. This finding can be used to formulate a rule for determining the law-of-karma-governed consequences of puruṣārtha. The rule is that consequences of puruṣārtha that do not change with time and place of puruṣārtha are governed by the law of karma.

The law of karma is a universal law, every puruṣārtha must, therefore, have universal consequences, i.e. invisible consequences. It can be seen at the outset that the subtle matter bound with the soul, termed karma, serves as a repository and a carrier of the invisible consequences of puruṣārtha. In other words, karma is the invisible consequences of puruṣārtha. The visibleand invisible consequences of puruṣārtha can be illustrated through examples.

A person was caught committing a theft and was sentenced for two years of imprisonment. The activity of committing theft is his puruṣārtha and the imprisonment is the consequence of his puruṣārtha. Another person receives remuneration for doing a job. The activity of doing job is his puruṣārtha and the remuneration he received is the consequence of his puruṣārtha. Both these consequences, imprisonment and remuneration, vary from one country to another; and they were different in the past from the present and will be different in the future. In other words, such consequences of puruṣārtha change with time and place of puruṣārtha and are, therefore, visible consequences of puruṣārtha that are not governed by the law of karma. Such consequences are governed by the man-made laws that are not universal. It should be pointed out that both the puruṣārtha of theft and job also have the invisible consequences (karma), as every puruṣārtha attaches karma to the soul. It may be pointed out that entities such as food, clothes, profession, etc., which serve as one of the causes of puruṣārtha, are the visible consequences that are not governed by the law of karma.

Let us take one more example. A person spends several days planning the murder of an enemy, but failed to do so because the enemy left the country. Is he going to experience consequences of his puruṣārtha of planning the murder? Though there are no visible consequences of his puruṣārtha, he surely is going to experience invisible consequences of his puruṣārtha i.e. he surely is going to attach karma. There are, therefore, puruṣārtha that have no visible consequences but karma. We, therefore, should not be unconcerned in performing those puruṣārtha that have no visible consequences.

It may be mentioned that there are visible consequences of natural events also besides puruṣārtha; these visible consequences also are governed by natural laws other than the law of karma. The loss of properties or lives due to floods, fires, earthquakes, etc. are not controlled by the karma doctrine. The visible consequences are the nimitta kāraṇa of puruṣārtha, as discussed later.

The inference that only invisible consequences are controlled by the law of karma has implications on the interpretation of the functions of the vedanīya and gotra karma. The commonly accepted explanations that the vedanīya karma controls the means of happiness and misery and the gotra karma is responsible for high and low family status is not supported by the inference. Both means of happiness and misery as well as the high and low family status are the visible consequences of puruṣārtha that are not governed by the law of karma.

The Nature Of Karma And Karma Phala

Karma phala is the consequences of karma (invisible consequences). As karma phala are born by the person who performs puruṣārtha, karma phala affect that person. We can understand the nature of karma and karma phala if we can understand the effect of karma phala on persons who perform puruṣārtha. Human beings are composed of two dravya (substance), namely,a mundane soul and living matter which are constantly undergoing modification. Matter that has association with a soul is termed living matter[6]; bodies of living beings are made of living matter, as they have association with a soul. Living matter has additional attributes besides the attributes of non-living matter. During modification the soul and living matter do not lose their attributes, but the paryāya (mode) of living beings, specified by the paryāya of the attributes of the soul and living matter, change constantly. The soul and living matter have many attributes and paryāya of all attributes are constantly changing. We will choose one attribute of knowledge of the soul for illustration. The paryāya of the attribute of knowledge of the soul of a person changes as he reads a book on computer science. The paryāya of the attribute of knowledge of his soul before he begins to read the book is different than that after he finishes reading it.

What is the cause of the change in the paryāya of the attribute of knowledge of his soul? It is the common understanding that the puruṣārtha of reading the book is the cause of the change in the paryāya of the attribute of his knowledge. But this assertion tells the incomplete truth. The illustration includes two paryāya of the person; the paryāya before he begins to read the book, i.e. pre-paryāya and the paryāya after he finishes reading it, i.e. post-paryāya. These two paryāya of the attribute of knowledge of his soul are related to each other. The pre-paryāya is the cause of the post-paryāya and the post-paryāya is the effect of the pre-paryāya. The pre-paryāya is the upādāna karaṇa of the post-paryāya. The karma phala of the jñānāvaraṇīya (knowledge-obscuring) karma is the nimitta karaṇa of the change in the paryāya of the attribute of knowledge of his soul.

The effects of karma phala of other karma on other attributes of the soul and living matter can be analyzed in a way similar to the karma phala of the jñānāvaraṇīya karma. From the above discussion it can be concluded that karma phala change the paryāya of the attributes of the soul and living matter of living beings. As karma phala are the consequences of karma, it can, therefore, be deduced that the nature of karma is such that their consequences, i.e. karma phala, only change the paryāya of the attributes of the soul and living matter, nothing else. Means of happiness and misery and the high and low family status cannot be the karma phala; they, as explained later, are the nimitta kāraṇa of puruṣārtha which, in turn, affects karma phala.

It may be pointed out that the attributes of the soul and living matter are universal; they do not change with time and place of habitation of living beings. The fact that karma phala affect the attributes which are universal substantiate the findings that karma (invisible consequences) are universal.

Role of Puruṣārtha in Karma Phala

A question arises about the role of the puruṣārtha of reading the book in changing the paryāya of the attribute of knowledge. The answer to this question can be found by identifying the upādāna karaṇa and the nimitta karaṇa of fruition of the jñānāvaraṇīya karma. The jñānāvaraṇīya karma itself is the upādāna karaṇa of fruition of the jñānāvaraṇīya karma and the puruṣārtha of reading the book is the nimitta karaṇa of fruition of the jñānāvaraṇīya karma. It should be pointed out that puruṣārtha is essential for the fruition of karma.

The change in the paryāya of the attribute of knowledge of the person’s soul would be different if he reads a book on mathematics instead of computer science, or if he listens a spiritual discourse instead of reading the book. Though his pre-paryāya and the state of the fructifying jñānāvaraṇīya karma do not depend on the puruṣārtha he performs, but his post-paryāya would be different for his different puruṣārtha. It is possible for him to perform any one of the countless of potential puruṣārtha, such as puruṣārtha of writing a novel, listening to music or a discourse, watching television or an entertainment program, analyzing past or future events, thinking about the nature of a soul, and so on. In these examples of potential puruṣārtha, book, novel, music, discourse, past or future events, soul, etc. are the potential entities; and reading, writing, listening, watching, analyzing, thinking, etc. are the potential activities. It should not be difficult to come up with the goals of various potential puruṣārtha. All entities, which are the means of the change in the paryāya of the attributes of the soul and living matter, are either natural or the visible consequences of puruṣārtha; they are not determined by the karma doctrine. The karma doctrine controls only the intensity, not the means, of the change in the paryāya of the attributes of the soul and living matter. Humans have freedom to pick the means of the change in the paryāya of the attributes of the soul and living matter

The above analysis of puruṣārtha reveals that only one of the causes of puruṣārtha is partly controlled by the karma doctrine. One of the causes of puruṣārtha is entitites; the entities of puruṣārtha are the visible consequences of puruṣārtha which are not determined by the karma doctrine. The entities are not controlled by the karma doctrine and they act as the nimitta kāraṇa of puruṣārtha. The other cause of puruṣārtha is yoga-plus-moha; itis controlled by the pre-paryāya of the human being, which in turn is partly controlled by the karma doctrine. Yoga-plus-moha is the upādāna kāraṇa of puruṣārtha and it is the only cause that is partly governed by the karma doctrine. This finding can be used to formulate a rule for determining the cause of puruṣārtha that is not governed by the law of karma. The rule is that the cause of puruṣārtha which is dependent on the visible consequences is not governed by the law of karma.

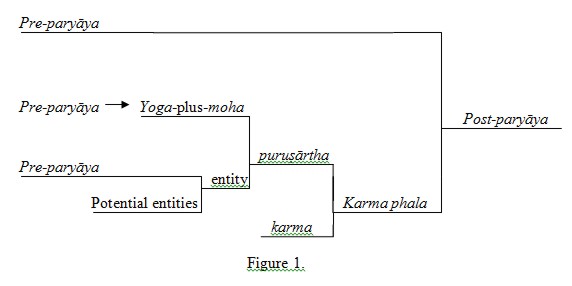

The role of the karma doctrine can be explained using the schematics in figure 1.

The post-paryāya is determined by the karma phala and the pre-paryāya; the karma phala is controlled by the puruṣārtha and karma; puruṣārtha is governed by entity and yoga-plus-moha; and entity is selected among potential entities by pre-paryāya. It may be noted that if karma phala is fully controlled by the karma doctrine, then the paryāya, both pre-paryāya and post-paryāya, also is fully controlled by the karma doctrine and the free will has no role to play. But that is not the case. The karma phala is controlled by puruṣārtha which, in turn, is not fully controlled by the karma doctrine as explained above.

Peculiarities Of Puruṣārtha

There are infinite entities in the universe, but all entities are not the potential entities. Only those visible consequences which are accessible to a person are the potential entities of puruṣārths of the person. For example, a person wishes to perform a puruṣārtha of owning a diamond. The diamond would become a potential entity of his puruṣārtha only if he has resources to own the diamond. The accessibility to visible consequences is not controlled by the karma doctrine; it is controlled either man-made laws or natural laws other than the law of karma.

The nature of activities depends on the entities. For example, the activity is eating for the entity of food; the activity is reading for the entity of book; the activity is analyzing its consequences for the entity of loss of wealth; and so on. Because entities are not controlled by the karma doctrine, the nature of the activities, which depends on entities, also is not controlled by the karma doctrine. However, the yoga-plus-moha, which is controlled by the pre-paryāya of the person,which, in turn, is partly governed by the karma doctrine, controls the intensity of the activities.

The actual entity of puruṣārtha is selected from the potential entities by the person who performs the puruṣārtha. As living beings are composed of a soul and living matter, the soul of the person select the actual entity. Based on the pre-paryāya of the person the soul selects the actual entity from the potential entities.

For a given pre-paryāya of a person, the actual entity is determined from the set of potential entities. Because the set of potential entities, in general, is not predetermined, the actual entity, and hence the puruṣārtha, also are not predetermined.

A large proportion of daily activities of humans after some time in the life become automatic. The automatic activities imply that the selection of actual entities from the potential entities also becomes automatic and does not require any special human effort. Though the routine human activities by definition are puruṣārtha, they in common parlance are not considered as puruṣārtha because of the lacking of the special effort to perform it.

Free Will

It is interesting to note that: if none of the causes of puruṣārtha is controlled by the karma doctrine, then puruṣārtha (present deeds) does not depend on karma (past deeds) and the karma doctrine becomes meaningless: and if both causes of puruṣārtha are fully controlled by the karma doctrine, then puruṣārtha is fully controlled by the karma doctrine and free will has no role to play in performing puruṣārtha. As only one of the causes of puruṣārtha is partly controlled by the law of karma, free will has a role in performing puruṣārtha.

Puruṣārtha is a function of entity and yoga-plus-moha; entity is a function of potential entities and pre-paryāya; and yoga-plus-moha is controlled by pre-paryāya. These statements can be written as

(1) puruṣārtha = function (entity, yoga-plus-moha)

(2) entity = function (potential entities, pre-paryāya)

(3) yoga-plus-moha = function (pre-paryāya)

Substitution in (1) for entity from (2) and yoga-plus-moha from (3) yields

(4) puruṣārtha = function (potential entities, pre-paryāya)

Every human has countless potential desires that result in countless potential entities. Based on his pre-paryāya he selects one entity among the potential entities to meet one of his desires. Pre-paryāya and potential entities are independent of each other. For a given pre-paryāya the actual entity varies with the set of potential entities; hence it is not possible to predict the actual entity for the given pre-paryāya.

Human has freedom to select one entity among the potential entities, but his freedom has some constraints. He cannot select the entity beyond the potential entities and in opposition to his pre-paryāya.

Conclusions

For the karma doctrine to be meaningful in the context of free will, the law of karma should control only one of the two causes of puruṣārtha. The analysis of the characteristics of the law of karma, karma and karma phala shows that one cause of puruṣārtha is yoga-plus-moha which is controlled by the karma doctrine and the other cause is entity that is not controlled by the karma doctrine. The karma doctrine controls only the intensity, not the means, of the change in the paryāya of the attributes of the soul and living matter. Humans have freedom to pick the means of the change in the paryāya of the attributes of the soul and living matter.

Prof. Subhash C. Jain

Prof. Subhash C. Jain