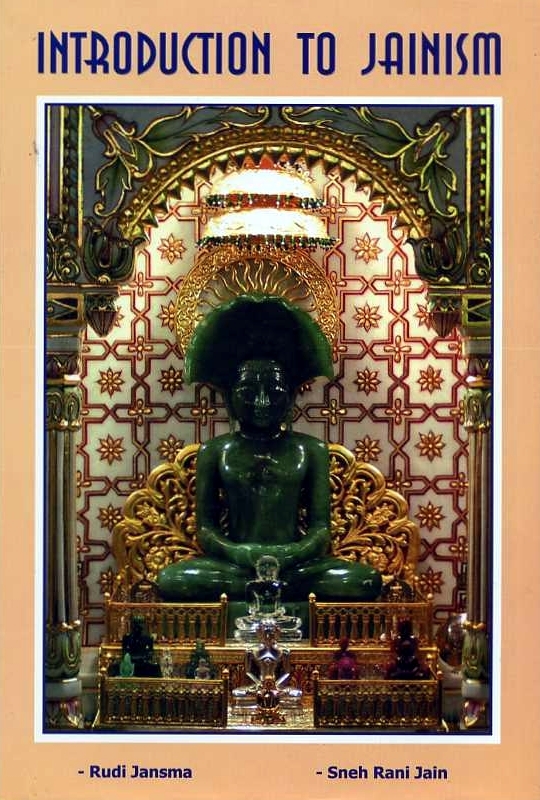

The instruments and skills reached a high level of development during the Parśvanāth period when the Nāgavanshis started to make idols of Nāgarāja (literally the Serpent King) and of paired serpents. The Nagarcoil temple of Nāgarāja near Cape Comorin (Tamil Nadu) is said to be very old. A stolen Jina from that period from Kalinga in Bihar is famous from literature, but it is not known where the icon is now. Like the Indus torsos the Jinas here were made of black touchstone or of granite, and also of red sandstone. Jinas of this period can be seen in most of the old Jain temples (photo 24).

Sitting Śāntināth, the 16th Tīrthamkara, 2500-3000 years old; rough 5th phase

Sitting Śāntināth, the 16th Tīrthamkara, 2500-3000 years old; rough 5th phase

photo 24

Sitting Śāntināth, the 16th Tīrthamkara, 2500-3000 years old; rough 5th phase

The approximately 3000 year old Jina of Jinthur (Maharashtra) in touchstone is one of the first attempts to make a detached sculpture of hard stone, and is therefore one of the earliest pieces of fifth style art. The arms are partly free, but quite cunningly the artist lets the sculpture lean on a frame on which he has carved plants (photo 25). The style in which he has done this links this piece of art with an early Indus style. This image therefore fills the gap between the older Indus style and the standing Parśvanāth of Chandragupta (photo 26), which is supported almost entirely by a curled seven-headed serpent.

Standing Jina of kasauti stone, 5th phase

Standing Jina of kasauti stone, 5th phase

photo 25

Standing Jina of kasauti stone, 5th phase

Parśvanātha in the Chandragupta temple on Chandragiri; approx: 350 BC

Parśvanātha in the Chandragupta temple on Chandragiri; approx: 350 BC

photo 26

Parśvanātha in the Chandragupta temple on Chandragiri; approx. 350 BC.

Long before the fifth stage in hard stone was reached, images were made of limestone covered with charcoal paste. The Jina of Paithan (the 20th Tīrthamkara, Munisuvrata) Rāma and Sitā are said to have used personally for their worship, is an example of this (photo 27). Despite its very great antiquity this image shows the fifth stage of art, long before such images could be made of touchstone or granite, as can be seen on the previous two photos. This was far more difficult in stone, and these two photos show early efforts.

This sculpture in a different technique may be thousands of years older, Paithan

This sculpture in a different technique may be thousands of years older, Paithan

photo 27

This sculpture in a different technique may be thousands of years older, Paithan

The intention to express the beauty of penitence by means of icons of the Jinas was a reflection of the desire to express the noble qualities of the soul, and with it one also depicted the celestial and other nonhuman beings which were at the service of the Jinas besides the support they received from humans. One can see Jinas accompanied by attributes and heavenly servants such as protectors, bodyguards, and gatekeepers.

On the picture shown here of the Indus seal we see on the right an ascetic devoted to penitence (arms down), accompanied by three (in physical reality invisible) celestial beings holding swords or sticks above the ascetic’s head for protection.

Temples in the North Indian city of Jaipur (Rajasthan) also have such black touchstone sculptures, but most are made of white marble, though not always of a very good quality. In the old temple of Ladnun, North of Jaipur, a splendid statue of Ādināth has been found. Most later statues were made in the period which begins with King Vikrama - from about 50 BC, and in fact continuing to the present - of which period quite a few early icons can be seen in old temples. Historians tend to accept the Ādināth of Mathura blindly as the oldest, by which they create an enormous gap between the factual truth told by the Jains themselves and their own historical imagination. The original art we have seen in on the hills and in the caves of South India is unique and much older than the finds in Harappa and Mohenjo-daro.

Long after the Harappan period, in the fourth century BC, there was a schism between the nude Digambaras and those who became the white-dressed Śvetambaras. The Śvetambaras “converted” many nude statues by removing their genitals. At the same time the marble art jumped ahead. At the time of the (European) Middle Ages one made astoundingly rich ornamentation, and the images were surrounded by marble celestials. Most Śvetambara temples represent this lavish form of art, as can be seen at the temples of Dilwara on Mount Abu and Ranakpur (both in West Rajasthan) which are well-known to foreign tourists. The same trend was followed in the temples of pink sandstone in Khajuraho of which no square inch is left without decoration. Celestial beings were also depicted with mudras (hand postures). This tradition continues until today in all its splendor, as evidenced by temples in new housing development areas (photos 29 and 30).

Interior of a modern Svetambara temple; Malviya Nagar, Jaipur

Interior of a modern Svetambara temple; Malviya Nagar, Jaipur

photo 29

Interior of a modern Svetambara temple; Malviya Nagar, Jaipur

Interior of a modern Svetambara temple; Malviya Nagar, Jaipur

Interior of a modern Svetambara temple; Malviya Nagar, Jaipur

photo 30

Interior of a modern Svetambara temple; Malviya Nagar, Jaipur

Regrettably the Jains themselves show little interest in their cultural heritage in stone. They attach value primarily to a number of places of pilgrimage where, apart from the icons, almost nothing can be seen of the glorious past which is now threatened by renovations.

Note: Shortly after I met her Dr. S.R. Jain went on an excursion within the framework of her research to “Virgin Rocks in India” and I joined her as a photographer. The information used in this chapter was written by her and used with her permission. - RJ.

For much more and deeper information about these subjects see the following books by Dr. S. Rani Jain:

Jain, S.R.: The Key Indus Rock of Karnataka, 2003; © Dr. S.R. Jain, Station Road, Sagar MP, India.

Jain, S.R.: The Ethical Message of Indus Pictorial Script, 2002; J.K Jain, Indrapuri, Bhopal MP, India.

Dr. Sneh Rani Jain

Dr. Sneh Rani Jain

Publisher:

Publisher: