As the skill of the artists improved they increasingly tried to separate the sculptures from the bedrock. But it was difficult to make the ears and limbs completely free and at the same time maintain the balance of the image. Because they worked with hammers and thick spikes, the possibility of damage was considerable when trying to free the relatively thin limbs from the stone, and therefore a connection with the bedrock was necessary. In this period brass art advanced rapidly and many sculptures were made in metal. The beautiful copper objects showing the twelve angas - which were then still in existence - were also made in this way (photo 21).

Depiction of the 12 holy books (angas) in a temple in South India

Depiction of the 12 holy books (angas) in a temple in South Indiaphoto 21

Depiction of the 12 holy books (angas) in a temple in South India

Many old temples in South India also possess copper objects depicting the Nava Devata (the nine objects of worship of the Jains, which include the arhats, the doctrine, and the communities of monks and of nuns). This stems from the period before Mahāvīra - so they are more than 2500 years old. The vidhyadharas (technicians) also made molded images of sand and lime, which were plastered black with a charcoal paste based on resin and gum to protect them against humidity and weathering. In this way one was able to make movable statues, which one could not or dared not yet do from hard stone types like granite and kasauti, also called touchstone (because it can be used to test gold). An example is the sculpture made by the vidhyadharas Nīl and Mahānīl which was installed by King Karakandu Naresh of Cambay (Gujarat) during or even before the Parśvanāth period, in the very old Dharaśiva caves near Osmanabad in Maharashtra of Ādināth and Nemināth (which cave was already there in the days of the Hindu avatar Rāma). Another example is the Jina of the temple of Thirumalai (Tamil for: the mountain which takes (the aspirant) away from the world towards liberation) near Chennai in Tamil Nadu.

Slabs of rock were used to make four-sided sculptures, and the square pillar pieces known as chaturdiki, which were decorated on each of their four sides with sitting and standing Jinas. The largest chaturdiki, ever found can be seen on a naturally square boulder near Tirukkoil in Tamil Nadu, which is almost as big as “two elephants on top of each other.” The first icons made from stone slabs were sitting Jinas - these are easier to make than standing ones. In the beginning the work was still rough and the long ears rested on the shoulders to support the head - almost as they were in reality, because the rich used to have long stretched ears caused by heavy earrings. Long ears are always among to the physical features of Tīrthamkaras as well as Buddhas. Freeing the arms of the image was still a problem (photo 24).

Sitting Śāntināth, the 16th Tīrthamkara, 2500-3000 years old; rough 5th phase

Sitting Śāntināth, the 16th Tīrthamkara, 2500-3000 years old; rough 5th phasephoto 24

Sitting Śāntināth, the 16th Tīrthamkara, 2500-3000 years old; rough 5th phase

But in time one learned to make freestanding sculptures out of granite and kasauti stone, as were found at Harappa and Mohenjo-daro in the form of torsos of standing Jinas in sandstone. Such statues were also found in Lohanipur near Patna (Bihar) and Mathura (Uttar Pradesh). The standing Jina of the temple of Śāntināth (the 16th Tīrthamkara) on the Vindhyagiri also represents this art style. This sculpture shows no decoration whatsoever; the only purpose was to show the serenity of a Jina dedicated to penitence - just as we have seen on the Key Indus Rock.

Apparently the pilgrims in those days approached the hill from the little village of Jinathapuram and were guided by engraved sketches on the rocks, which led them along the sacred boulder to the top, so that they could do their mandatory obeisance ritual (pūja). Monks climbing the Vindhyagiri to take sallekhana (peaceful death by fasting) lived in the shelters among the rocks and revered this rock and the manastambha even from a distance. The Śāntināth temple was built later, and still later was visited by Bhadrabahu, Emperor Chandragupta’s guru, who went there in the fourth century BC with a large group of followers from the North during a prolonged famine. Still a number of years later, some 2350 years ago, the temple named Kattale Vasadi with sculptures of Parśvanāth and of yakshas and yakshinīs - these are local male and female celestials, which devote themselves to serving a Jina - was reportedly added by Emperor Chandragupta Maurya himself.

Another good example of Jain art consists of the wall paintings in some of their old temples. The Jina-Kanchi temple near Kanjivaram in Tamil Nadu contains over 2000 year old wall and ceiling paintings depicting Prathamanu-yoga stories - karma and reincarnation stories. The Matha temple in Śravana Belagola shows paintings, which are almost 2000 years old depicting samavasaram –the birth of a Tīrthamkara - and events from the lives of Bāhubali. We also find well preserved paintings on the walls of the more than 2500 year old caves of Thirumalai in Tamil Nadu. In old temple walls on the Vindhyagiri we find painted elephants and horses in red and white which look as if they were made yesterday, but were actually made more than 1100 years ago (photo 23).

Ancient wallpainting: Vindhyagiri

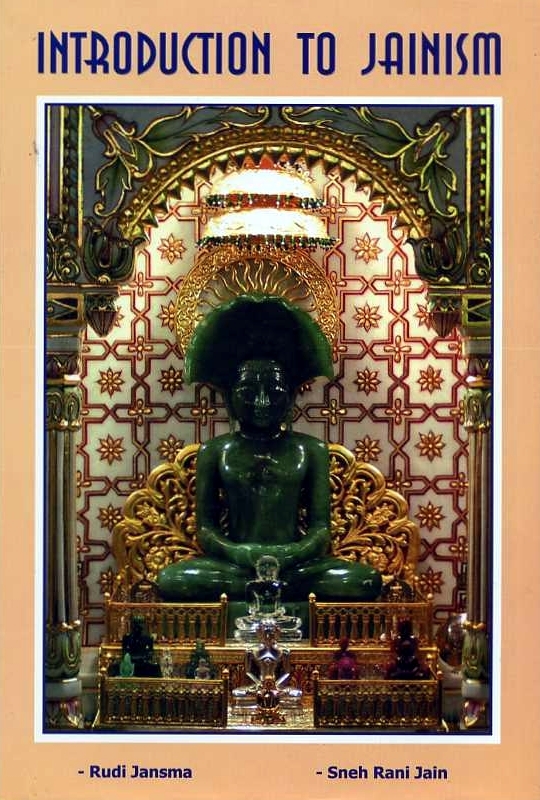

Ancient wallpainting: VindhyagiriMany images were made of precious or semiprecious stone and kept in temples only to be shown on particular occasions. Most of such sculptures are of the first Tīrthamkara, Rishabha. Often miracles are connected with such statues, which the people regard as inexplicable mysteries. In our day, too, there still exist mystery statues, which produce actual miracles, as we have seen in chapter 8. Such large blocks of precious or semi-precious stone, might sell for millions of dollars or euros or crores of rupees, and many people in the world would rather not see them converted into religious idols to be donated to a temple. But this is exactly what the Jains did and do, because they realize that the inner value of the soul is priceless and worth much more than any worldly gain, which they regard as merely worthless dust. To understand that, one almost needs to be born as a Jain. A real Jain attaches no value to a dead body, and not even to his own living body. Therefore there are no Jain burial places, graves or mummies. Throughout the history of Jain culture no mummy has ever been found, but through the ages one has given utmost attention to spiritual messages by means of script, symbols or sculptures on rocks and in caves which will guide the soul on its upward path. This is the only goal worth striving for.

Dr. Sneh Rani Jain

Dr. Sneh Rani Jain

Publisher:

Publisher: