The inner value of the soul is priceless and

worth much more than whatever worldly gain,

which they but regard as worthless dust.

When was the art of writing invented? According to the Jains it was the first Tīrthamkara, Rishabha, who taught humanity the six skills. Art was one of 72 specializations, and drawing was part of the art of writing.

If we wish to learn something about the early art of the Jains, we must turn to old caves and hills all over India, and especially those in the East, and in the South in Karnataka and Tamil Nadu, to inscriptions and engravings in the massive rocks left untouched by time. In the oldest Jain temples as well, much can be seen. The people who lived in the South in those days (and partly even today) were the Dravidians, who were followers of a particular group of Jain ascetics (S.R. Jain, personal communication). According to historians the original Dravidians have long since been driven away from their lands.

An archeological survey presents an amazing richness of antique art objects, old scriptures, paintings on walls and ceilings, icons, symbolic diagrams (yantras) with geometrical drawings and written mantras, used for paying homage in highest concentration to some highly honored Jina, and also lessons noted down in the form of prathamanu yoga stories.[85] Enormous rocks high up in the hills show us Jain art in the form of granite engraved sketches, relief sculpture, engraved footprints, paintings, and scriptural signs, which are also reflected in the Indus culture. According to official science the art of the Jains covers a period of at least 7000 years, and these precious forms of art are still being added every day in our modern times. There are numerous reasons to suppose that this culture is far older than 7000 years. In the evolution of art a number of phases can be distinguished, but until today nobody has been able to give an exact date to the finds in stone.

Though much remains today for us to investigate, through the centuries, but especially in modern times, enormous damage has already been done to the ancient art of the Jains. Rival religious groups have constantly tried to erase Jainism from the surface of the earth, to burn their original books (with complete success, as far as we know), and to destroy or damage their artistic accomplishments. Conquerors from elsewhere have done their bit. Nowadays damage is mainly being done as a side effect of tourism and (deliberate?) neglect by institutions like the Archeological Survey of India and the State Archeological Departments in this Hindu dominated country. Tourists are attracted by more conspicuous objects such as large images and temple complexes, but walk with their feet and “their eyes closed” on things, which are of far more value from an archeological and cultural point of view. These things have however been neglected or hardly investigated and publicized, and have often been misinterpreted due to bias. All this is so old that it partly stems from times when no dispersal of cultures and religions as we know today had taken place in India. Moreover what we find is so rich that the United Nations should recognize it as World Heritage, and the international community should ensure its protection.

The Jains have always carefully protected their sanctuaries in the cave temples in the South Indian hills, the Saurashtra Hills of Girnar (West Gujarat), and many other places in India. They deliberately and purposely kept them secret from possible intruders and gave them no publicity outside Jain circles. On places which are often difficult to reach one can find well-preserved or damaged chaturdikis (small or large pillars with sculptured pictures of standing or sitting Jinas on four sides), yantras, manuscripts, paintings, copper works of art; and all this together provides us with detailed information about the art of the Jains. The author and photographer owes it exclusively to the Jains themselves who - because of his lifestyle and the genuine respect he has for them - revealed to him the things he has been able to see. In the temples there are sometimes manuscripts which provide information about the art of the Jains in the form of drawings.

As reported the Dwadas-anga (the 12 angas), scriptures existed until Mahāvīra’s period, around 2600 years ago, but from then on they were lost or destroyed, and they were preserved only in the memories of holy men and monks who knew them by heart. But the scriptures themselves as well as the exact record of what was contained in them were lost, partly because of neglect, partly because of the rivalry of the Brahmins (who base themselves on the Vedas - the authority of which is denied by the Jains and Buddhists), the “lingites,” worshipper of the linga, the symbol of the Hindu god Śiva, and also the Buddhists. In Mahāvīra’s days there were many local wars between small kingdoms, of which the Jains became victims after the loss of the Nanda dynasty. Jains ascribe the disappearance of their palm-leaf manuscripts to great fires which raged in the two great universities of those days: Nalanda (in Bihar, in the Northwestern part of India) and Taxla (now in Pakistan near Lahore). Nalanda later bloomed as a famous Buddhist university, and its sizeable ruins are now a tourist attraction. Some old temples have free-standing pillars (manastambhas.[86]) with depictions of the cosmos together with the Jain śruti-skandhas, the collection of above-mentioned 12 angas, complete with a description of the contents per volume. But the texts themselves have been lost (according to the Digambaras, but the Śvetambaras still claim to have 11 of them) - with the exception of part of the twelfth anga, which was found more than two thousand years later in South India near Mangalore, and on which the Digambara Jains in the recent centuries have found material matching later scriptures on which they based their reconstruction of all twelve angas. In front of most temples we can find a manastambha, a high slim stone pillar with on top a chaturdiki with its four carved Tīrthamkaras. Manastambha means “ego pillar,” because those who look up to it and see the lofty conquerors of all passions who have left all mundane affairs behind forget their egos (mana) and know that reality is beyond all attributes of the ego. Some temples have objects of brass or other metals with depictions of the twelve scriptures, which prove that this literature existed five centuries BC.

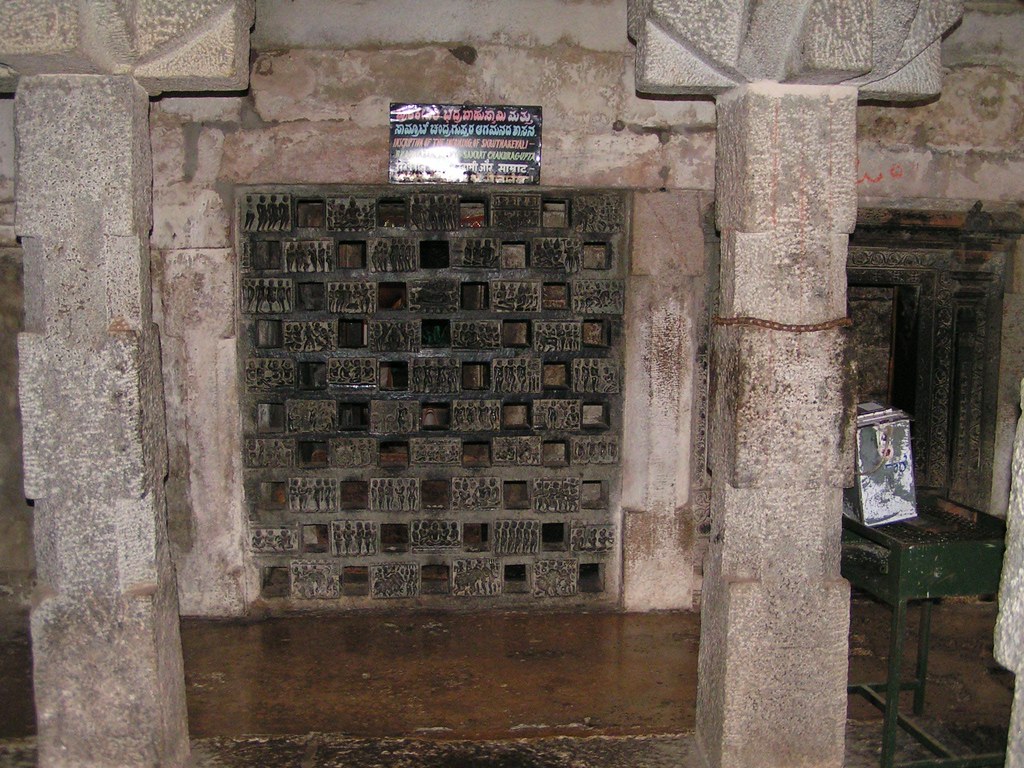

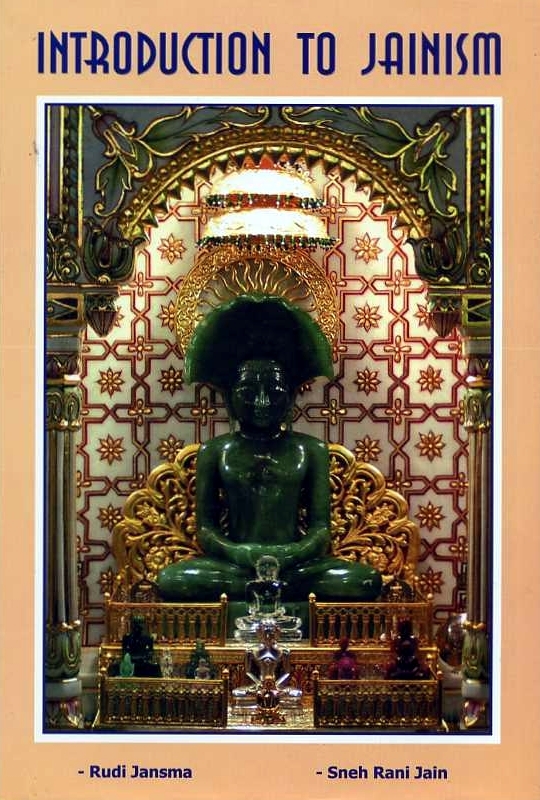

In the temple of India’s great emperor Chandragupta Maurya,[87] on the “Chandra Mountain” at Śravana Belagola in Karnataka we find a statue of Parśvanāth (the last-but-one Tīrthamkara, who lived about 800 BC; see photo 26) and of local deities (yakshas) dating back over 2000 years. The jali or openwork granite screen (photo 8) constructed as two fences, through the open spaces of which one can see the Parśvanātha statue in the room behind, show important episodes in the life of emperor Chandragupta Maurya. Photo 9 shows a detail.

Stone screen depicting the life of Emperor Chandragupta Maurya, 350-300 BC

Stone screen depicting the life of Emperor Chandragupta Maurya, 350-300 BC

Photo 8

Stone screen depicting the life of Emperor Chandragupta Maurya, 350-300 BC

Stone screen depicting the life of Emperor Chandragupta Maurya, 350-300 BC.

Stone screen depicting the life of Emperor Chandragupta Maurya, 350-300 BC.

Photo 9

Stone screen depicting the life of Emperor Chandragupta Maurya, 350-300 BC.

Parśvanātha in the Chandragupta temple on Chandragiri; approx: 350 BC

Parśvanātha in the Chandragupta temple on Chandragiri; approx: 350 BC

Photo 26

Parśvanātha in the Chandragupta temple on Chandragiri; approx: 350 BC

Prath(a)manu yoga stories are texts which paint in vivid colors the repeated reincarnations of various important personalities of the spiritual or lay community of the Jains, which indicate which karmas have brought about which results in subsequent lives.

The Hindu Śivalingam have, according to Jains, evolved from the Jain manastambhas, because several Jain stupas were converted into Śivalingams, but can still be identified from their shape: rectangular at the base, octangular in the middle and oval at the top.

Dr. Sneh Rani Jain

Dr. Sneh Rani Jain

Publisher:

Publisher: