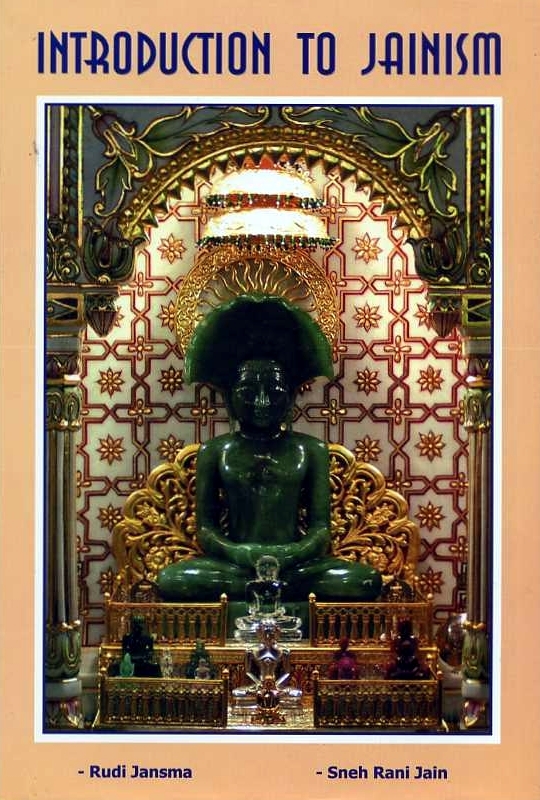

We had a so-called miracle temple within our walls. Real miracles sometime happen there, Brahmāchārinī told me. It was one of the temples on the monastery’s grounds, dedicated to Śantināth (the 16th Tīrthamkara), which daily attracts a lot of visitors who symbolically – by means of rice grains, nuts etc. – come to offer all their good deeds and part of their basic needs to the service of the higher beings. Though Jainism recognizes no creative God, it does recognize many entities which have been humans, but have attained godhood, as well as many “demigods” (and even “demidevils” – as we have discussed earlier). These demigods (and devils) were once men and women, and still have five senses and a highly developed intelligence while residing in their own world. During their existence on earth they may have built a special attachment to a particular place, guru or a statue of a Jina. Also due to the occult consecration of such a place by an advanced monk possessing the necessary knowledge is qualified in that field – possibly centuries ago – several aspects of a good and religious man or woman who has passed away may linger there. An example of this was the three-man-high statue of Śantināth in our temple. The worshipers make obeisance to the statue. But the image is just stone, and does nothing. The Tīrthamkara himself, or any siddha who lives in siddhaloka, is not involved in any worldly matters whatsoever. But the invisible beings around the sculpture can, if and when they want sometimes give a sign, or perform a “miracle” as the simple-minded say, because their realm of existence enables them to do things that are impossible on our physical level. Sudden cures may take place, or somebody is rained upon by saffron spray, etc. It doesn’t happen often, but when it does – and that can only be in agreement with the karma of the person involved – such an event is of course a psychological boost for the rest of that person’s life. As a result of their tremendous self-control, advanced monks such as the guru of this community also have control over unseen powers, i.e. beings. Brahmāchārinī herself had been cured at least once in such a way.

The monks continued their daily routine. Apart from eating and drinking once a day, they all have to go to the “toilet” every day; all at the same time, at a fixed hour. In a long line, all of them carrying a water container and of course their peacock brush, they come out one by one through a side door. It is the only time that they actually move out of the monastery grounds when not traveling. They walk quite a distance away from the grounds to find a proper place. Their only free moment, one might think. But no, their life during the day is completely public, and so they are followed by a mob of onlookers who want to see how these holy men do what they have to do. In silence they tread their “path of duty” and afterwards return to the temple in the same manner. After that they try to study and meditate, always in a sitting posture, because lying down is something they only do at night. Try … because they are approached by pious people, who kneel down in front of them with hands joined, head on the ground: “namustu, swami, namustu, swami, namustu.” The swamis make a blessing gesture with their right hand and then the devotee leaves him. There is no room where the ascetics can withdraw and be alone for. All rooms are public domain. People constantly come to beg for their blessings and to ask questions. The monks seem to be completely unaffected by what happens around them. I asked one monk how he could stand it, all this adoration and perhaps not always very intelligent questions. But he had no problem. Calmly he answered the result was that in any case beneficial. For the questioner at least if he or she was listening seriously, but if not then for himself, because in this way he gave a spiritual lesson. I would explode in irritation and despair. Not they. Irritation is an emotion which attracts undesirable karmic molecules which will become an obstacle for the liberation of the soul, and they will not allow themselves to do such a thing.

The highest form of pure behavior, only exhibited by ascetics who have tremendous stamina and enlightened knowledge, is a form of ascetism named pariharavisuddhi – meaning total abstinence from violence, which entails fasting for an extended period, restrictions on the types of food to be taken, meditation, and service to fellow monks. All this should be done in a state of total mental and emotional equanimity. In agreement with the rules, nine monks join hands and follow uninterruptedly for nine month this severe path of penitence. In the Śvetambara (but not in the Digambara) tradition, six monks practice this ascesis during the first six months, and four others carry the responsibility to serve the four fasting monks. This is necessary because their bodies can become very weak, and because they engage in meditation only. One of the four serving monks is chosen as āchārya. During the second phase of six months their roles are reversed, but the same person remains the āchārya. In the third period it is the task of the monk who served as the āchārya for the last twelve months to practice – as the only one left – his ascesis. One of the other eight monks now becomes āchārya and the other seven serve him (Pacisavana Bola p.146).

But the command over body, emotions and thoughts must also be stainless during the regular life of monks. In the days I spent there I saw no sign of irritation or depression in their faces. Still, inwardly they may or may not be constantly confronted with emotions and inner conflicts. Of the fourteen-fold path to the liberation of the soul they have only reached the third to fifth stage, or exceptionally the sixth stage. The guru can, in his best moments, reach the seventh stage, I was told. But even then a very long and difficult path lies before him. The next chapter discusses this path in some detail.

What inspires people to begin such a life? In the first place they must have an undreamed-of love for all that lives: to give up all worldly enjoyments because they do not wish to inflict any harm or pain on any living being. Externally their life is completely relaxed: no family, no troubles, no mobile phones to recharge, no text messages from whiny girlfriends, no fear of missing the latest download, no jealousy, because no one has anything to be jealous about. Their emotional life has become entirely internalized. Jainism knows only simplicity and philosophy; there are no complex rituals no secondary gods of various kinds to whom people can beg for personal help. One can only travel the path alone. Pure motives will lead to pure results. One already has to have quite an intelligence to distinguish the essential from the senseless: the thousands of rituals and forms of worship and prayer with which so many religions entertain the people and which have perhaps some effect, but distract from what is essential – or to become an autonomous and fully developed human being. Therefore most of those who choose such a path will be intellectuals with a deep spiritual confidence.

Brahmāchārinī was an example of this. With a university education and a broad scientific interest, a successful academic career behind her, unmarried and childless, but with the heart of a mother and a grandmother at the same time, she spent hours sitting in pure devotion at the feet of her guru. She kept strictly to the rules she found useful, but for other ones she did not care. The guru had great respect for her and gave her hints for her research – they have known each other for decades, and, whenever possible, where he goes, she goes. She regards it as her scientific task and ancestral duty and is prepared to postpone her own salvation a few lifetimes for this. What merit is greater than abandoning even that most spiritual of all egoisms: the subtle desire to reach the liberation of your soul for the benefit of yourself alone?

The deepest motivation for leading a monk’s life is to reach omniscience, salvation and nirvāna, leaving all mundane matters and false desires behind. An eternal, immortal, spiritual life is in store. From a man one becomes a god. Therefore one bends one’s spiritual thinking and acting always towards universal love, nonviolence and purity and the acquisition of a perfect unlimited clarity of mind to avoid illusion. For this purpose one gives up or avoids yielding to any impulse from the evanescent: physical as well as psychic and mental desires. They can stand pain, hunger, thirst and discomfort thanks to their deep belief that they are not identified by their body, but that they are their soul, which only needs to do away with the physical body and all other karmic bondages to free itself. Because of their absolute separation of spirit and matter they can abhor the body while glorifying the soul. Still they do not inflict any harm on their bodies, and there is no self-torture in Jainism: that would be an act of violence against the billions of living beings of which the body is composed.

I asked the youngest of the monks whether it did not frustrate him that he would have to wait so long before reincarnating in a period when there would be an embodied Tīrthamkara on earth to instruct him directly – tens of thousands of years in the future. But he had a cheerful answer to that: after his death in his present incarnation he would be born and live as a celestial being for a long period of time (by earthly standards) in a body of a more subtle type of matter than our physical senses can perceive, but that nevertheless is as real as the body we are used to at present. In this condition there is no earthly time concept, and tens of thousands of years would go by in a flash. So, soon he would be able to live in the company of a Tīrthamkara on earth, and then he would be able to reach final liberation by his own effort – to become a Jina, a conqueror.

The great example for the monks is Bāhubali, the first human being to reach liberation in this cycle. An abundance of statues of him are to be found in numerous temples and on sacred sites. Therefore I should first tell you the story of Bāhubali.

Dr. Sneh Rani Jain

Dr. Sneh Rani Jain

Publisher:

Publisher: