On the other hand, genes made Paul a man and Madeleine a woman, thus making possible their sexual attraction. They met at the age of maximum reproductive potential, a time when biology throws young people at each other with enough force to tilt the earth. Both had genes that made them attracted to the opposite sex; perhaps a simple variation could have made Paul sexually attracted to Madelein's brother. Genes might have also influenced how the relationship developed was Madeleine a genetically driven thrill seeker? Did she pursue the ship's captain because she craved a new high? Or was it harm avoidance that caused Paul to flee at the first sign of trouble instead of sticking with Madeleine when she was confused? We are products of our genes, so it is natural that our relationship, too, will fall under the sway of DNA.[73]

One afternoon at the HIV clinic, after I had finished an interview, the subject asked me why I was so interested in his family history. When I explained that we are trying to see if sexual orientation was influenced by genes. He made an interesting suggestion: "You should look at the sex chromosomes. That is what makes men different from women." In fact I was interested in the sex chromosomes, not so much because of their role in making men and women different as because of their distinct pattern of inheritance. Specifically, fathers transmit their single Y chromosome to each of their sons and their single X chromosome to each of their daughters. This generates unique family trees and makes the sex chromosomes easy to track.[74]

It was prominent scientist Botstein who had, in 1980, proposed that it might be possible to map the entire human genome by using random bits of variable DNA called markers. The second principle that influences linkage is that genes found close to one another on a chromosomes usually are inherited together. Because of simple chemistry, two genes that are "close together" are, by definition found on the same DNA molecule. DNA is tough and wiry: only rarely do its long strands break in two. As a result, genes that are located on the same piece of DNA almost always travel together into the germ cells that make up the fertilized egg.

To understand how genes help shape who we are, rather than just what we suffer from, it helps to start with something simple and move to more complex areas of behavior. The first example is something most people take for granted. Genes make us all alike "when people hear a trait is influenced by a gene, they sometimes assume it only comes in two opposite varieties: smart or stupid, mean or kind, passive or aggressive, we know that physical characteristic such as height, weight and skin color don't come in just two varieties so we must assume that the variations of personality are equally vast. Just look in the mirror. Facial features are largely determined by genes but there is nobody else in the world (unless you have an identical twin) who looks quite like you. Given the wonderful diversity with which genes sculpt the human face, they must be equally dexterous and imaginative when it comes to shaping the nooks and crannies of human brain. Such breath taking detail on the outside of the human form suggests an equal, or even more elaborate, construction on inside.[75]

Bailey, J.M. and R.C. Billard, "A genetic study of male sexual orientation" Achieves of General Psychiatry 48, 1089-96, 1991.

Meyer - Bahlburg, H.F.L. 1982, "Psychoendocrine research on sexual orientation" - Progress in brain research 61: 375-98.

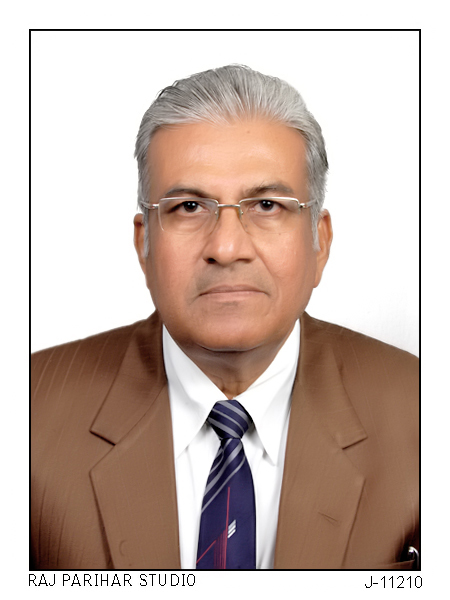

Prof. Dr. Sohan Raj Tater

Prof. Dr. Sohan Raj Tater

Doctoral Thesis, JVBU

Doctoral Thesis, JVBU