The teachings of Mahavira are characteristically simple, practical and ethical, but they have gradually developed into a detailed, intricate system, relating not only to the nature of the true and the ideal, but also to the practical path for their realisation. The ultimate object of the teaching of Mahavira is liberation or salvation, which can be attained through annihilating karma attached to the soul. It can be achieved by the practice of austerities and preventing the influx of additional karma through self-restraint of the body, speech and mind. Liberation of the soul is a state of perfection, of infinite bliss in an eternal abode, where there is no ageing, no disease, no cycle of birth and death and no suffering. Mahavira was very practical, possessing universal vision. His explanation of the six 'real entities' displays his deep insight into the nature of the universe. A number of his teachings, for example, argue that spoken words can be heard throughout the universe (modern radio broadcasts); that microscopic germs are engendered in excreta, sputum, and urine; and that plants have life, are now widely accepted by science.

His teaching of the five vows of 'non-violence', truthfulness, 'non-stealing', sexual restraint (and restraint of the activities of the sensory organs), non-attachment, and his theories of 'relative pluralism', guide ethical thinkers today. His descriptions of the range of mental states and 'psychic colours' are supported today by some psychic researchers and theosophists, and what we would today term science and psychology were as important to him as spiritual knowledge. Elements of his teachings are now seen to have been centuries ahead of their time, as having a recognisable 'scientific' basis, and are relevant even to present-day concerns. His teaching consists of the threefold path of Right Faith, Right Knowledge and Right Conduct, which together lead to liberation, the status he himself achieved.

The Threefold Path

The ultimate object of human life is liberation or salvation, the purification of the soul (moksa). Jainism describes how the path of purification is to be achieved through one's own efforts. The Tattvartha Sutra, one of the most sacred texts of Jainism, emphatically states in its first aphorism that Right Faith (samyag darsana), Right Knowledge (samyag jnaana), and Right Conduct (samyag caritra) together constitute the path to the state of liberation. These are called the three jewels of Jainism. These three are not to be considered as separate but collectively forming a single path, which must be present together to constitute the path.

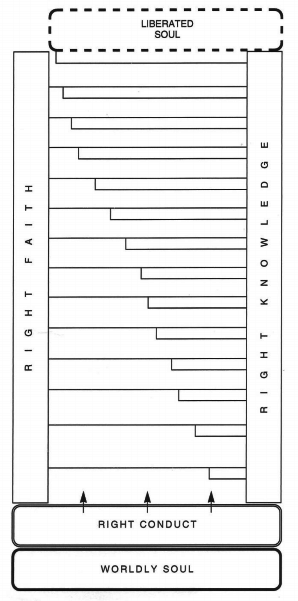

In the view of this firm conviction, the Jain seers over emphasise that these three must be pursued simultaneously. By way of illustration, one could use a medical analogy: In order to bring about the cure of a disease, three things are essential, faith in the efficacy of the medicine, knowledge of its use, and its ingestion by the patient. Likewise, to achieve liberation, faith in the efficacy of the path, knowledge of it and the practising of it - these three together are indispensable. Similarly, the path to liberation is compared in Jain works to a ladder: The two sides of the ladder represent right faith and right knowledge, and the rungs of the ladder represent the (fourteen) stages of right conduct. It is obvious that it is possible to ascend the ladder only when all the three elements, the two sides and the rungs, are intact. As the absence of sides or rungs would make a ladder ineffective, so the absence of one element makes the spiritual ascent impossible.

Figure 4.1 'Ladder' of spiritual progress showing the fourteen steps.

Right Faith

The term Right Faith (or the right attitude, right vision or right belief), samyag darsana, has been defined in the Tattvartha Sutra as the true and firm conviction in the existence of the 'real entities' of the universe. Right Faith. The Uttaraadhyayan (28: 14,15) defines Right Faith as the belief in nine 'real entities' (nava tattvas). The Niyamsaara (1931: 5) explains the Right Faith as the belief in the liberated souls, Jain scriptures and the "real entities'. Samantabhadra defines samyag darsana as the belief in true deities, true scriptures and true teachers (Ratnakaranda sraavakaacaara 1955: 4) and mentions eight essential characteristics of Right Faith and the necessity of renunciation from eight types of pride.

The Jain scriptures emphasise that Right Faith should be characterised by eight essential requisites or components. These are:

- One should be free of doubt about the truth or validity of the Jain tenets.

- One should be detached from worldly, materialistic things.

- One should have an appropriate regard for the body, as the body is the means by

which one achieves liberation, but one should feel no 'attachment' to it.

- One should take care not to follow a faith or path which will not lead to liberation; one should avoid harbouring credulous or superstitious beliefs.

- One should foster spiritual excellence, and protect the prestige of the faith from belittlement, by praising the pious and not deriding others.

- One should be steadfast in one's convictions and help others towards the path of Right Faith and Right Conduct, whenever they falter.

- One should have affectionate regard and respect for the virtuous and one's coreligionists, and show due reverence towards the pious.

- In one's own conduct one should demonstrate Jain values and teachings: one should attempt to demonstrate the Jain concept of true religion both through religious observances and in the performance of charitable deeds, such as the provision of food, medicine, education and shelter to all those in need.

The first five are for the self and the last three are the duties of the community. A true aspirant should always be ready to help others.

Right Faith should be free from erroneous beliefs such as:

- Pseudo-holiness: Some people falsely believe that practices such as bathing in certain rivers or fire walking are a means of acquiring merit for themselves or for their family.

- Pseudo-gods: Some people have faith in gods and goddesses who are credited with divine and destructive powers, but praying to such deities in order to gain worldly favours is false faith, leading to karmic bondage.

- Pseudo-ascetics: Some self-styled ascetics consider their teaching to be the only truth, but such ascetics should be recognised for what they are and should not be sustained in the hope of gaining favours through their magical or mysterious powers.

Jainism teaches that the mind must be freed from eight forms of pride: learning; worship; family; status by birth (or contacts and family connections); power (including physical strength); wealth or achievements; penance or religious austerities; bodily beauty or personality.

Any form of pride disturbs the equilibrium of the mind, creating likes and dislikes, and in such case discretion, judgement and the 'vision' may be clouded and can lead to error.

The Jain texts describe at length the importance of Right Faith and they enumerate the benefits that can be accrued by a person possessing it, and note that asceticism without Right Faith is inferior to faith without asceticism; even a humble believer with Right Faith can attain spiritual progress.

The Uttaraadhyayan (28: 16-27) classifies aspirants of the Right Faith into ten categories according to the methods of attainment:

- Intuition: those who have inborn inclination towards righteousness.

- Tuition: those who learn by instructions from others.

- Command: those who obey the command of the enlightened people.

- Sutra: those who obtain righteousness by learning the sutras.

- Seed: those who have an inner attitude that grows like a seed.

- Study: those who study the sacred texts.

- Comprehension: those who learn truth by logic and comparison.

- Conduct: those who observe Right Conduct and the rituals as prescribed.

- Exposition: some aspirants understand truth though a brief exposition

- Dharma: those who believe in the Jina and follow his teachings.

The Aacaaranga Sutra (1.3: 2.1) argues, ' He who has Right Faith commits no sin'. The texts imply that a person with Right Faith should possess the moral qualities such as fearlessness, detachment, freedom from negativism or scepticism, alertness, selflessness, sincerity of purpose, single minded devotion, calmness, kindness and the desire for selfrealisation. Such individuals should have friendship towards all, appreciation of the virtuous, compassion for the underprivileged, indifference to those, who do not listen to them or other enlightened individuals, and should be free from egoism or pride in any form.

Right Knowledge

Any knowledge which facilitates spiritual progress is by definition Right Knowledge. Right Faith and Right Knowledge are closely related as are cause and effect, an analogy of which might be similar to a lamp and light: One may have a lamp without light, but not light without a lamp, similarly, one may have Right Faith without knowledge, but not knowledge without Right Faith.

The scriptures describe Right Knowledge as 'that knowledge which reveals the nature of things neither insufficiently, nor with exaggeration, nor falsely, but exactly as it is and with certainty'. It has also been stated that Right Knowledge consists in having full comprehension of the real nature of living beings and non-living things, and that such knowledge should be beyond doubt, misunderstanding, vagueness or uncertainty (Sanghave 1990: p.40).

Jain seers assert that knowledge is perfect when it does not suffer from the above three defects of insufficiency, exaggeration and falsehood, as these pervert both one's understanding and one's mental and behavioural attitudes. The Jains have developed a systemic theory of knowledge, which is discussed in chapter 4.5, and five forms of knowledge:

- Sensory knowledge (mati jnaana): is knowledge of the world acquired by means of any or all of the five senses and the mind.

- Scriptural knowledge (sruta jnaana): is derived from the reading or listening to the scriptures, and mastery of such knowledge may make one a 'scriptural omniscient'.

- Clairvoyant knowledge (avadhi jnaana): is a form of direct cognition of objects without the mediation of the sensory organs. This knowledge apprehends physical objects and events, which are beyond the normal grasp of the sensory organs, and is acquired in two ways: (1) Inherent in both celestial and infernals and acquired in the case of humans and animals. Celestial beings possess a higher quality of knowledge than their hellish counterparts. (2) One can acquire clairvoyant knowledge by progressing on the spiritual path, but its degree differs according to one's spiritual progress. The soul of the tirthankara is born with an extensive type of clairvoyant knowledge.

- 'Telepathic' knowledge (manahparyaaya jnaana): is direct cognition of the mental activity of others, and can be acquired by those who are spiritually far advanced; some call it 'mind-reading' knowledge, although the terms 'telepathic' and 'mindreading' are inadequate translations.

- Perfect knowledge or 'omniscience' (kevala jnaana): is full or complete knowledge of all material and non-material objects without limitations of time or space. It is the knowledge possessed by all souls in their pristine state and its acquisition is the goal for a human life.

Right Knowledge has eight requirements:

- The reading, writing and pronouncing of every letter and word of the religious texts should be undertaken correctly with care and faith.

- Reading should be directed towards understanding the meaning and full significance of the words and phrases of the texts. Mere mechanical study without understanding the meaning serves no purpose.

- For Right Knowledge, both reading and understanding the meaning are essential, as they together complete the process and the purpose of knowledge.

- Study should be undertaken in quiet places regularly and at times when one is free from worries and anxieties. · Humility and respect towards the scriptures and the teachers should be cultivated.

- If one encounters difficult expressions and ideas while studying, one should not jump to hasty conclusions that may lead to an improper understanding.

- Enthusiasm for mastering of a subject is essential to sustain an interest so that one continues to study.

- One must keep an open mind and attitude so that prejudice will not hinder a proper understanding and the completeness of knowledge.

Thus, Right Knowledge is acquired by studying the scriptures through understanding their full meaning and significance at appropriate regular times, imbued with zeal, with a correct attitude and an open mind.

The Uttaraadhyayan (28: 30) states that without Right Faith there is no Right knowledge; without Right knowledge there is no Right Conduct and without Right Conduct there is no liberation. For liberation, perfection in Right Faith is the necessity, whereas it is unnecessary to know more than the bare fundamental truths of spirituality. All knowledge of a wrong believer is wrong knowledge. Jainism gives more importance to conduct and faith than knowledge, and believes that knowledge is a power that can be utilised only by a person having the right attitude.

Right Conduct

After Right Faith and Right Knowledge, the third, but the most important path to the goal of liberation, is Right Conduct,, and Jainism attaches utmost importance to it. Right Faith and Right Knowledge equip the individual with freedom from delusion and with the true knowledge of the 'real entities'. Right Knowledge leads to Right Conduct, which is why conduct that is inconsistent with Right Knowledge, is considered to be wrong conduct. The conduct is perfected only when it is harmonised with Right Faith and Right Knowledge.

Right Conduct presupposes the presence of Right Knowledge, which, in turn, presupposes the existence of Right Faith. The Jain seers have enjoined upon those who have secured Right Faith and Right Knowledge to observe the rules of Right Conduct.

Right Conduct includes rules of discipline which:

- restrain all unethical actions of mind, speech and body;

- weaken and destroy all passionate activity;

- lead to non-attachment and purity.

Right Conduct is of two types, which depends upon the degree of practice or the rules of behaviour:

- Complete or perfect or unqualified conduct.

- Partial or imperfect or qualified conduct.

Of these two forms of Right Conduct, the former involves the practice of all the rules with zeal and a high degree of spiritual sensitivity; the latter involves the practice of the same rules with as much diligence, severity and purity as possible. Unqualified and perfect conduct is aimed at, and is observed by ascetics who have renounced worldly ties. Qualified and partial conduct is aimed at, and observed by, the laity still engaged in the world. The various rules of conduct prescribed for both laymen and ascetics constitute the ethics of Jainism.

One of the most striking characteristics of Jainism is its concern with ethics, which has led some to describe Jainism as 'ethical realism', while others have called it a religion of Right Conduct. Jain ethics see no conflict between the individuals' duty to themselves and their duty to society. The aim of the Jain path is to facilitate the evolution of the soul to its 'highest capacity' and the means to achieve this is through ethical conduct towards others.

The ultimate ideal of the Jain way of life is perfection in this life and beyond, yet Jainism does not deny mundane values but asserts the superiority of spiritual values. Worldly values are a means to the realisation of spiritual values, and the activities of everyday life should be geared to the realisation of spiritual values (dharma), leading to liberation (moksa). Liberation is attainable through a gradual process of acquiring moral excellence, and Right Conduct is a very important element of the threefold path of purification. Ethics for the Jains is the weaving of righteousness into the very fabric of one's life.

One may achieve different levels of Right Conduct in one's life: complete and partial. The complete commitment to Right Conduct entails the vigorous practice of Mahavira's teachings through the renunciation of the world and adoption of the ascetic life. For the majority who has not renounced the world, it is still possible to seek the truth 124 and pursue the path of righteousness, although to a lesser degree. This is the path for laypeople, often referred to in Jain and other Indian texts as 'householders'. This path represents a more attainable form of social ethics. The two level commitments, of the ascetic and of the householder, are a characteristic feature of the Jain social structure. Laypeople have the (appropriate and moral) obligation to cherish their family and society; the ascetics sever all such ties.

The ethical code of the Jains is based on five main vows for both the ascetic and the householder. These vows are unconditional and absolute for ascetics and are called major vows (mahaavratas), but they have been modified as minor vows (anuvratas) in consideration of the social obligations of householders. The vows are 'non-violence' (ahimsaa), truthfulness (satya), non-stealing (acaurya), celibacy (brahmacarya) and nonattachment (aparigraha). Though these vows, taken at face value, appear to be merely abstentions from certain acts, their positive implications are extensive and they permeate the entire social life of the community.

Five Main Vows

'Non-violence' (Ahimsaa): Ahimsaa is the opposite of himsaa, which may be translated as 'injury' and defined as any acts, including thoughts and speech, which harm the 'vitalities' of living beings. The nature of these 'vitalities' is described later in this section. Harm, whether intended or not, is caused through a lack of proper care and the failure to act with due caution, but the meaning of himsaa is not exhausted by this definition and a more detailed examination of the concept is found in the next section.

Truthfulness (Satya): The opposite of truthfulness is falsehood (asatya). In simple terms, asatya is words that result in harm to any living being, even unintentionally. This is why Jainism teaches that the utmost care must be taken in speaking. The implication of this vow is extended to prohibit spreading rumours and false doctrines; betraying confidences; gossip and backbiting; falsifying documents; and breach of trust. Other examples of falsehood would be the denial of the existence of things, which do exist, and the assertion of the existence of non-existent things; or giving false information about the position, time and nature of things.

One's speech should be pleasant, beneficial, true and unhurtful to others. It should aim at moderation rather than exaggeration, esteem rather than denigration, at distinction rather than vulgarity of expression, and should be thoughtful and expressive of sacred truths. All untruths necessarily involve violence. One should protect the vow of truthfulness by avoiding thoughtless speech, anger, and greed, making others the butt of jokes or putting them in fear. Even if a person suffers through telling the truth, Jain teaching holds that truthfulness is ultimately always beneficial. Interestingly, the motto of the Republic of India: 'truth always wins' (satyam ev jayate), accords with Jain teaching.

Non-stealing (acaurya): Theft (caurya) is the taking anything which does not belong to oneself or which is not freely given. To encourage or to teach others to commit theft, to receive stolen property, to falsify weights and measures, to adulterate foods, medicine, fuels and so on, and to exploit others are all considered forms of theft. To evade the law, for example, by tax evasion or selling goods at inflated prices and to act against the public interest for personal benefit or greed are also theft, and one should guard oneself against it. The vow of non-stealing is comprehensive, covering the avoidance of dishonesty in all areas of life. As material goods are external 'vitalities' for people, whoever harms them, e.g. by stealing, commits violence.

Celibacy (brahmacarya): The vow of celibacy (brahmacarya) literally means 'treading into the soul', but conventionally it is taken to mean abstinence from sexual activities. The vow prohibits sexual relations other than with one's spouse and the consumption of anything likely to stimulate sexual desires. Ascetics, of course, abstain totally from sexual activity. Jain teachings also discourage excessive sensual pleasures.

Lack of chastity (abrahma) is considered to take several forms. The search for marriage partners should be limited to one's immediate family. Matchmaking by those outside the family is contrary to Jain teaching. Unnatural sexual practices, using sexually explicit or coarse language, visiting married or unmarried adults of the opposite sex when they are alone, and relations with prostitutes (of both sexes) are all forms of lack of chastity. Misusing one's senses, such as reading pornography or seeing explicit films, should be avoided.

Non-attachment (aparigraha): Attachment to worldly things or possession (parigraha) means desiring more than is needed. Even the accumulation of genuine necessities can be parigraha, if the amount exceeds one's reasonable needs. Other examples of parigraha would be greediness or envy of another's prosperity. In a similar way, if one were in a position of influence or power, such as in a voluntary or political organisation, but did not make way for another person when one should have done so, that would be a form of 'possessional' attachment.

The five vows described above, together with 'relative pluralism' and austerities form the basis of Right Conduct. Relative pluralism is the fundamental mental attitude, which sees or comprehends 'reality' from different viewpoints, each viewpoint being a partial expression of reality. Austerities, as discussed in the Satkhandaagama, are the extirpation of desire in order to strengthen the three jewels of Right Faith, Right Knowledge and Right Conduct. The ethical code and austerities are discussed later in this section.

The soul, which is the central theme in Jain philosophy, has traversed an infinite number of cycles in the universe and occupied differing types of bodies. The knowledge of the 'real entities' of the universe (discussed in the next chapter) and their usefulness to the soul is necessary for its spiritual advancement. The soul guides itself and other souls towards spiritual progress. Matter serves the soul by providing the body, necessary for spiritual advancement, through which a soul expresses itself, provides nutrition, and objects of comfort and material pleasure.

Dr. Natubhai Shah

Dr. Natubhai Shah