The First Manifesto of the Anuvrat Movement

Man is a rational being. His activity is mental to begin with and becomes physical subsequently. Thus all his actions result from his thinking. This is the process in relation to both man's problems and their solutions. The problems arise naturally in the course of a man's activity; the solutions, however, have to be sought out by special effort and are outside the given course of activity. Thus, for example, the tongue demands good taste; this demand, being natural, is freely indulged in; excessive or injudicious intake of food gives rise to disease. In order to overcome the suffering caused by the ailment, the question of finding relief confronts the sufferer. He resorts to medicine. The ailment disappears. But the story repeats itself. The offender returns to the pleasures of the palate: he eats to satisfy not his hunger but his craving for taste. The problem reappears and defies a solution. This repeated need for a solution arises because the man in question wants to pamper his palate as well as remain free from ailment. This is the vicious circle, all too familiar, of repeated indulgence of the senses and repeated recourse to relief.

Religion is spontaneous. It is not invented by man's intellect. What is invented is the use that is made of it. And it is here that the process of subterfuge starts. A man acts wrongly. His mind is consequently in unrest. In order to allay his unrest he takes refuge in religion. He supplicates before the Supreme Being. As a result he gains some relief - some peace of mind. But again his activity adopts a wrong course and once more the old unrest and the old recourse to religion repeat themselves. The man in question seeks religion not to mend his ways but to secure for himself immunity from the consequences of his wrong deeds both here and hereafter. In other words, he wears religion as a protective armour so that he may continue to indulge in his wrong ways. It is nothing but playing with religion. In other words it is self-deception.

Now the Anuvrat Movement advocates the path of vows which leads to self-restraint. It enjoins on its adherent the resort to religion, not as a means of absolving him from sin but as a means of avoiding sin. Religion - in the sense of moral values - resides in a pure heart. The aim of the Anuvrat Movement is to ensure that life becomes pure, that truth and honesty govern the daily activities of the people and that the moral basis of life widens itself.

Jainism, Buddhism, Hinduism. Islam, Christianity, etc. are so many modes of religious belief. They are not religion in its pure sense but so many forms of interpreting the truth that is religion. For the essential religion admits of no labels - it is not the right of patent either of this or that ism. It is one and the same for all people. In the wake of the great prophets and teachers who interpreted religion in the light of their understanding of it, religious beliefs and practices arose and consolidated themselves as organised religions that we know. But the actual spirit of religion is something that each individual in search of it must realise for himself in his own life and endeavour. This central spirit of religion is ahimsa (not to destroy or injure life). The manner and the extent in which this principle is interpreted and embodied in action are liable to differ but the validity of the principle itself is not subject to any difference of opinion. The method of churning may vary but the butter that comes out from the churning is the same, though the quantity may differ with the difference in the method or intensity of churning. Ahimsa is this essential element in all religious beliefs. Truth, non-stealing, abstinence and non-possession - these are but the different forms of ahimsa. Restraint in food, simplicity, etc. are all different ways of realising this principle. The Anuvrat Movement aims at offering the common man the universally acceptable principle of life so that the practice of essential religion may grow and the narrowness and intolerance associated with the so-called forms of religion may diminish.

The Way to Reconciliation and Tolerance

I will not cause displeasure to others' itself ensures the pleasure of others. 'I will cause pleasure to others' is a course which is both difficult and disputable. Thus, for instance, some people are inclined to think that in order to give pleasure to the more developed forms of life it is quite excusable to cause displeasure to the less developed forms. Some, again, think that in order to cause pleasure to man, the causing of pain to all other forms of life, whether more or less developed, is quite in order. Yet others think that in order to promote the pleasures of the more fortunate beings the causing of pain to the less fortunate beings is excusable, while there are still others who think that it is not justifiable to cause displeasure or pain to anyone in order to promote the pleasure of others. Thus there are many conflicting lines of thought regarding the second course of action (viz. *I will cause pleasure to others'). It is not likely that these differences can be straightened out. To quarrel on the ground of these differences is to lose sight of the central spirit of religion: to indulge in himsa is to become irreligious. In these circumstances the right approach to religion would be to seek out the area of agreement amongst all religious forms and to make the same the basis of a universal code of conduct so that in place of inter-religious strife and hostility a feeling of tolerance is developed. One pledge which an anuvrati takes is, 'I will cultivate tolerance towards all forms of religious persuasion.'

It will be found that most of the rules set out in the anuvrat code are worded negatively and only a few positively. The reason is that positive injunctions cannot be framed in a way that they may be valid under all conditions. Such injunctions - do's - are dependent for their validity on such factors as the appropriateness of place, time, circumstances and the inclination of the person or persons concerned. The determining lines - of where, when, what and how much - cannot be drawn uniformly. On the other hand, prohibitions - don'ts - can be set out in a uniformly valid way. Every individual has the right to exercise his freedom, but only so far as the freedom of others is not interfered with. It is because individuals do not respect this fundamental law of freedom of their own accord that external restraints have to be imposed on them by society. In the last resort restraints, by their very nature, cannot but be negative for the most part. The individual who imposes restraints upon himself does not require to be brought under external restraints. It is through this self-imposed form of restraint that true resistance to temptation develops and self-control grows. Activity becomes pure to the extent to which impure elements are thus kept out.

The main aim of the Anuvrat Movement is thus to help develop in each individual the power of self-protection against the infection of impure conduct. As to the promotion of pure conduct, the impetus to action will depend on the individual's particular ideals and beliefs. It is not possible to outline the minimum areas of positive action in the same way as it is possible to delimit the minimum areas of negative action to general satisfaction. For in the matter of positive action the determining factors vary with differing viewpoints of the prevailing religious beliefs.

A Nonsectarian Movement

The Anuvrat Movement does not belong to any particular form of religious belief but to all forms of religious and moral belief. It is not meant for the followers of any particular faith but for the followers of all faiths. Since it concerns itself with character - the basic element in life - it makes no distinction between man and man on the score of qualification or status. The only qualification that the Movement recognizes is the preparedness on the part of the person concerned for self-restraint and self-examination; as for status, it is one that one confers upon oneself by electing to become an anuvrati (one who pledges himself to observe the anuvrat code).

A Movement for Building Character

This movement is one that aims at revolutionizing life from within by remaking character. The world today needs this more than anything else. If it has lost any one thing in a greater measure than all the rest, it is this basic element - character. One of the main causes of the world's present tragic condition is the deficiency of character. The necessities of life, ever increasing in their complexity, are apt to become more and more difficult to be satisfied, with the result that life itself becomes increasingly difficult. One answer to the problem that suggests itself is a more equitable distribution of wealth. The economic contours of a community or nation are never static: they can and do alter from time to time. In some countries the economic ups and downs have been reduced, levelled or reversed in living memory. And yet it cannot be claimed that these nations are as a result free from fear and distress. Even though possessed of easy access to the amenities of life they are as distraught as ever before. This shows that the path to peace and happiness is other than mere economic amelioration. The path is primarily that which has been outlined - the development of character. Given external amenities and comforts but no internal contentment, man has little hope of peace. Given neither exterior conditions of well-being nor interior contentment, he has still less peace. When external conditions are favourable and there is also internal contentment, it is nothing wonderful if peace prevails. But what is wonderful and possible is that peace and happiness can be achieved by inner contentment even in the relative absence of outer amenities of life. This is the secret of self-restraint.

The Common Basis of Morality

There is such a thing as the base of the pyramid of moral values in life and this base is common to all rational living. It does not matter whether the individual concerned believes or does not believe in an immortal soul, whether he likes or dislikes asceticism or severe austerity. A man who does not believe in the existence of the soul may not subscribe to total non-offensiveness (ahimsa) but even he will not advocate offensiveness {himsa) as a good thing in itself. Even those who believe in political expediency and even in political duplicity will not be found to endorse the conduct of their wives or husbands if the latter behave towards them with duplicity. For it is the most remarkable thing - the most redeeming thing - about those given to falsehood and dishonesty that they would like other people to evince towards them truth and honesty. Really speaking falsehood and wrongdoing but represent a man's failings - his weakness rather than his strength. The normal tendency of the rational mind is to conform to the moral law. It is merely to canalize this innate tendency that the vow-taking comes into play. The Anuvrat Movement is a project for the spiritual and moral rejuvenation of life.

The Anuvrats

Anuvrat means a small or diminutive vow. No vow, truly speaking, is either small or great. What is meant by a 'small' vow is a vow that is not accepted in its fullness. The term anuvrat is derived from the Jain ethics. Patanjali, the expounder of the Yogic philosophy, speaks of the five vows of nonviolence, truth, non-stealing, celibacy and non-possession as simply vrats when they are limited by considerations of time and place and as mahavrats (great vows) when not limited by such considerations.

The Purpose of Vow-taking

The purpose behind vow-taking is self-purification. Vows should not be taken for the sake of material gain or reform. Material welfare follows in the wake of the observance of vows but the aim in taking them should be solely self-rectification. If social reordering is what is sought, then such an objective is more directly achieved by political action than by means of these vows. But the objective that the vrats aim at is immensely higher than social or political good. It is spiritual good. And the spiritual good is not only the highest good but also the total good. It includes both one's own good and the good of others.

A Retrospect

This Movement arose from small beginnings. It could not then be imagined that it would grow into so expansive a movement. That people at large have realized its necessity and that Jains and non-Jains, in their thousands, have solemnly pledged themselves to the observance of its rules of life is a matter of great satisfaction. My vision has taken shape. In its fulfilment the cooperation of my followers - both clerical and lay - has been fully forthcoming. They placed before me their suggestions with regard to the rules and also what they considered necessary or desirable in the light of their own experiences. I have also freely benefited from the reflections of critics. Whatever was acceptable has been embodied in the code; what was not so acceptable has been left out. I am always prepared to accept suggestions that further the usefulness of the Movement along proper lines.

The tradition of taking vows is an old and time-honoured one in this land. I do not therefore claim to have brought a new institution into being. All that I can claim is to have put new life into the moral heritage that we possess and to have adapted it to the needs of the times. This I consider nothing more than my duty as a religious teacher. It is my earnest hope that the moral values embodied in the anuvrats will be accorded the allegiance of people of goodwill everywhere and that they will be increasingly realized in their lives despite adverse circumstances.

Money can buy books but not knowledge; it can procure medicine but cannot ensure health, can get servants but not service, can build temples but cannot inspire devotion. It is easy to avoid many frustrations and the maladies resulting from them if an atmosphere of freedom prevails in the family enabling its members to discuss their problems without any constraint. |

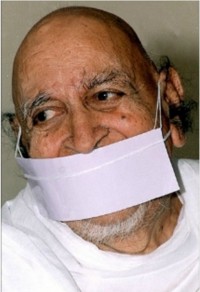

Acharya Tulsi

Acharya Tulsi