His way of life was simple. After leaving India he adopted clothes, which were suitable in a foreign country. He began to wear a jacket and trousers. But there, too, he maintained simplicity. After coming to Africa from India he gave up wearing a cap regularly and generally kept his head bare. Normally his clothes were washed and ironed at home. Even after he had become a multimillionaire his simple habits did not change. Addictions he had none. He was very particular about punctuality. He was always on time and expected others to be on time. On account of his punctuality and simple and peaceful habits he kept in good health. He did not resort to medicines but in the course of years his faith in natural therapeutics became firm. He worked hard in his business but never at the cost of his health. However burdened he was with responsibilities, he never took his worries home with him. He would go to bed early at a regular time and wake up at five in the morning. He had the habit of waking up early and making morning tea for Maniben and himself as well as for any guests who might be staying in the house, and this habit continued even after he married and employed servants. Why should he trouble others for his own comforts? For him, the early morning was a time of peace. After drinking his tea he would play cards with Maniben for an hour or so and this was his main means of entertainment. He maintained this routine regularly for years. In the early years in East Africa, when he was building up his business, he would set out early in the morning to take orders and deliver goods. Throughout his life he would work fourteen or fifteen hours a day.

His personal friend, Chimanbhai, remembers an incident about his habit of rising early in the morning. Once he was Meghjibhai's guest in London. Next day Chimanbhai was to go to Copenhagen on business and he had to take the plane at dawn. Chimanbhai was not used to getting up early. So, he requested Meghjibhai to wake him up early and then slept without worrying. Chimanbhai was sure that Meghjibhai would manage to wake him up early. At half past five next morning there was a knock on the door. Immediately on waking up Chimanbhai opened the door. He saw Meghjibhai standing at the door with a tea tray in his hands and a gentle smile on his face. This small but significant incident of Meghjibhai's unsurpassed modesty was stamped forever on Chimanbhai's memory. When Chimanbhai recollects the incident he says that the greatness of great men peeps out in habits that are considered to be small. Meghjibhai could have entrusted this ordinary responsibility to any member of his family, if he so desired. But it was not his custom to thrust upon others the work that he could do himself. He did not feel ashamed of doing any task. In his hospitality he never differentiated between important people and unimportant, nor between his own friends and relatives and strangers.

Mr. Amritlal Raichand Shah (who has contributed many memories of Meghjibhai to this book) remembers that when Meghjibhai came back to Kenya in 1962 for the wedding of his daughter Usha, he was given the use of a house and a car with driver. But he would not always avail himself of the car. Instead he would pay the fifty-cent fare to go into town by bus, getting off at the Khoja mosque and coming to A.R. Shah's shop for a chat. Mr. Kantibhai Punamchand Shah came from the same village as Meghjibhai though he was the latter's junior by some twenty years. He remembers the business of Premchand Raichand around 1941 when he worked there as a storekeeper and salesman. The offices were in the petrol station at the corner of Biashara Street and Koinange Street in Nairobi, with the godown opposite. Meghjibhai treated him as an older friend would, not as a boss, and Kantibhai would be invited home to the house in Blenheim Road.

Meghjibhai encouraged the young man to learn typing and English. Many years later when Kantibhai came to London, as a member of the Kenya Legislative Council, for the Lancaster House conference on Kenyan independence, Meghjibhai met him in London and was really pleased that Kantibhai had progressed so far. He learned much from Meghjibhai, not least from Meghjibhai's insistence on getting a balance sheet right (and not carrying a lost item into a suspense account). He remembers Meghjibhai's decisiveness, his impatience with committees and approvals and so on, his foresight in developing products and his skill in salesmanship (he was the first to sell tannin extract in Japan). Yet, for all his business acumen Meghjibhai was soft-hearted. One of his first priorities when he had made money was to provide a school building in Dabasang. He was not too proud to take advice from experts and would spend any money to make sure that his ideas, particularly for charitable trusts, were workable legally.

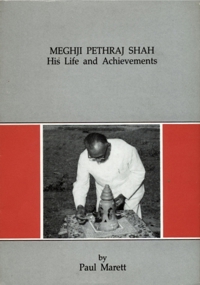

Along with a simple nature and a sympathetic heart he had an innate ability to discriminate between good and bad, worthy and unworthy. He was a man of medium height and powerful build, with discerning, penetrating eyes, which would accurately assess the worth of a man. He would not be pressurised into doing something, which he thought wrong. As he was well known for his generosity he was constantly approached by people collecting subscriptions or asking for donations. Often he had occasion to say no and he would do it gently without causing offence, quietly explaining the principles on which he worked. Some wealthy people enjoy the power of teasing and tormenting supplicants, or telling them to come back again and again. This was not Meghjibhai's way. Once he was convinced of the merits of a good cause he would make a decision to give without delay. If any matter was not right in his eyes he would not hesitate to disagree with anybody, however powerful, and he would not yield to pressure from people, however important they might be. He had a soft spot for those institutions, which were imbued with a spirit of service, and for social workers. He had a wonderful insight to discern true and sincere people. He never hesitated to express his love for such people and to encourage them.

Meghjibhai' s generosity in Saurashtra naturally led to people trying to get his support for undeserving projects but he refused to get trapped into these. He kept well clear of the hypocrisy that often masqueraded in the name of religion. He did not believe in rituals but he did not oppose them strongly. He disliked outdated social customs but his dislike did not extend to rejecting those people who still believed in them. He was distressed to see the condition of the society but did not blame the leaders of society for this. He knew well that society had degenerated on account of superstitions, blind faith, bad customs, illiteracy and poverty. It was no use finding fault with a few leaders for the degeneration of society. For the amelioration of society, illiteracy and poverty must be removed. He was never obsessed with narrow considerations of caste, community or sect. His aim was always to serve the general public and the nation irrespective of colour, caste or creed. This attitude was unprecedented in Saurashtra in those days and was a source of inspiration to others.

Dr. Paul Marett

Dr. Paul Marett