Meghji's native village was Dabasang, some eighteen miles from Jamnagar in Kathiawar (later known as Saurashtra). Dabasang was like any other Indian village, with most of the people working on small plots of land. In those days the population was perhaps 700 or so: nowadays some 1,500 people live there, with electricity and other modern amenities. Now, of course, forming the western part of the state of Gujarat, before Indian Independence Kathiawar was divided into a large number of princely states, more than 200 in all, some of them of fair size like Porbandar, Rajkot, Bhavnagar, Jamnagar, Limbdi or Junagadh. Within these kingdoms there were many local lords owning five, ten, fifteen, perhaps twenty-five, villages. The local 'squire' in Dabasang, Joravarsinhji, was a kindly man who took special care to ensure that the villagers experienced no harassment at the hands of his kinsmen. Joravarsinhji's son, Ramsinhji, became a close friend of Meghji and his family.

The village of Dabasang today is reached by a narrow but serviceable tarmac road running some three or four miles off the main road. Nowadays, it takes a short while by motor vehicle or motor scooter though the village does not see all that many motor vehicles even now. When Meghjibhai lived there in the early years of the century a journey to Jamnagar would take several hours on foot and would be considered a longish journey even in a light pony trap pulled by one of the sprightly little horses for which the region is famous. The ox cart, heavy and enduring made from solid baulks of timber, with spoked wooden wheels, drawn by two long-horned, slow-moving, tan-coloured oxen, was the usual form of farm transport and in Meghji' s childhood would have been the principal method of transporting goods from one village to another. Indeed, Meghji' s father earned some extra money with his ox cart, sometimes travelling several miles away. The slow plodding oxen are a timeless feature of Indian village life.

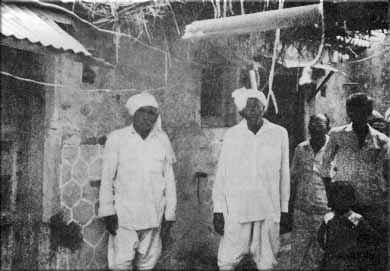

The village streets are narrow with the solid walls of the houses broken only by heavy studded doors. The house where Pethraj Jetha lived with his wife and family has hardly changed over the years and is at the end of a narrow turning off the main village street. A gate opens into a tiny courtyard. The room in the small single-storey house are dark, protected from the hot Indian sun, though there is electric light nowadays. The kitchen has a low fireplace in one corner of the floor for cooking. A simple wooden apparatus rests in a large pot for churning the morning milk to separate the curds from the buttermilk. Assorted containers to hold the family' s store of grain and other things are stacked around. The walls are plastered and whitewashed but very uneven; the underside of the heavy clay tiles may be seen above the open rafters of the sloping roof. Furniture consists of little but the charpoys, the typical Indian beds of woven cord on a low wooden frame (cooler than a mattress in a hot climate), up-ended against the wall when not in use. The family's clothes, neatly folded, are stored in a curtained recess in the wall. In one room in this house (they still know which room it was) Meghji was born. In the village, as he grew up, he would have seen the water carrier with his large round metal water container on an ox cart making his rounds of the village. Women in coloured saris collect water in big brass pots for the day's needs. In the busy seasons men are working in the fields, oxen pull simple ploughs, sheep and black goats are herded together, cows wander idly around munching at what growing plants they can find, a few long legged light brown dogs stretch out and sleep. Children play in the dust, which covers the dry ground.

Men who are not working sit around and talk, dressed in long white cotton shirts over cotton trousers, baggy at the top but tight over the calves (the prototype of the jodhpurs familiar in the West), a white cotton turban tied loosely around the head. Saurashtra is known as 'dry Gujarat', as distinct from 'green Gujarat' further east, and in years, when the monsoon rains fail (which happens not infrequently) the land is parched and the landscape is reminiscent of a desert, brown and dusty, with sparse bushes and trees providing the only touch of green. Even the cactus hedges, planted to protect growing crops from grazing cattle, wilt in the dry air. Only where a well retains water can the fields take on the lush greenness, which, in a good year, the rains will bring. When the rains fail and the crops fail the farmers have no income, the labourers have no work. Nowadays government aid can sustain at any rate a minimum subsistence. In older days drought would mean starvation though the Princes would provide help where possible. There is a Jain temple in the village, a whitewashed building fronting on one street, decorated above the door with a panel of coloured figures: although renovated every few years (Jain temples are usually well-kept) it is doubtless recognisably the same as it was when Pethraj Jetha and his family went there to pray.

As a child Meghji enjoyed the pastimes of the village boys, hide-and-seek around the houses and fields or flying kites. It is remembered that his enthusiasm for this pursuit led him into a near-fatal accident at the age of six. Disentangling the cords of two kites at the top of a tree he missed his footing and fell. Happily he was not badly hurt. In later life he remembered the lesson that your feet must be firm if you aim for the heights.

Dabasang was fortunate in having a small village school with a few pupils, established and maintained jointly by the local landowner and the village people. Here Meghji went to school when he was old enough. Endowed with a quick intelligence and a very good memory the boy distinguished himself effortlessly in his studies in the village school. His good memory was to stand him in good stead in his subsequent career and he also had a remarkable facility for mental arithmetic. His ability to carry out detailed calculations rapidly in his head was often a source of astonishment to those who had to have recourse to paper and pencil for simple sums. In these days of computers and electronic calculators we are apt to forget the advantage in a business career of a natural facility with figures such as Meghji possessed.

Meghji's full-time education had to end when he had passed through the five classes of the village school. The small income from the family land and shop was not enough to enable his family to send him away for further studies in a school in Jamnagar. However, just at this time a teacher's post in the village school fell vacant. Meghji had been one of the brightest pupils. His teachers recommended him for the vacancy, the leading people of the village supported this and he was taken on as an assistant teacher on a monthly salary of eight rupees. This was equivalent to about eight shillings (40p) sterling. To his parents, simple village people, it seemed that their son had scaled the pinnacle of success. Mr. V.G. Maroo, now living in Nairobi, can remember what the school was like in 1927, just a few years after Meghji left. He remembers a wooden building, tiled most probably with the traditional village-made small hemi-cylindrical tiles still to be seen on many older village buildings today. There was a single large classroom with a floor of beaten cow dung. The teacher had a table and chair but the children, mostly boys but a few girls, sat on the floor writing with slate pencils on slates. There was a headmaster with one assistant (Meghji's successor) who was a youth in his late teens. Gujarati, of course, was the language of the school but there was also a private English school, up to Standard Four, in the village. Meghjibhai did learn some English in the village, and it was probably in this school. It may seem strange to us nowadays that a young boy, barely out of primary school, should become a teacher like this. However, a paid working 'apprenticeship' was a normal way to start in teaching in the early years of this century.

A teacher had a very respectable position in Indian rural society and the young Meghji's future career seemed set on a steady, if not spectacular, course. There was nothing at this stage to suggest that this bright young village boy, from a respected but not wealthy family, would end his days as anything other than a village schoolmaster. Meanwhile, his prospects were such that his parents had found him a bride and the betrothal was followed by his marriage in 1918 to Monghibai daughter of Jeshangbhai Tejshi Shah and his wife Lakshmibai, of the village of Targhadi. The bridegroom was not quite fourteen years old but it must be remembered that such early marriages were the custom in those days.

Dr. Paul Marett

Dr. Paul Marett