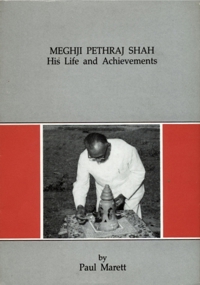

Meghji Pethraj Shah was born on Thursday, the 15th of September, 1904. In the traditional Indian calendar this was considered an auspicious date, the sixth day of the bright half of the month of Bhadrapada. His parents, Pethraj Jetha and Ranibai, were of modest means. They had some land and a small shop in the village of Dabasang, near Jamnagar, enough to support a simple way of life with nothing left over for luxuries. Jains by faith, of the Visa Oshwal caste, they were pious people and they brought their children up in an atmosphere of secure religious faith. Pethrajbhai is remembered as quite an ordinary man, fairly tall and stocky in stature and strongly built. He was not educated, but generous and open-hearted. He was on good terms with his neighbours and relatives and entertained them all without stint on special occasions even though sometimes he could ill afford such generosity.

Meghji was the third child. The eldest was a daughter, Lakshmi, then came three sons, Raichand, Meghji himself and, born two years after Meghji, Vaghji, the youngest of the family. Their father was well thought of in the village where his family had been settled for four or five generations. Life in the home of Pethrajbhai and Ranibai was simple and contented: the parents were devoted to all their children and were anxious to see that their sons got such education as they could afford, to fit them for life in business or some other suitable occupation.

In the early years of the twentieth century village life in India was 'civilised' but there were no modern comforts as understood in the West. In the villages there was no electricity, water would be drawn from wells, and there were no tarmac or concrete roads. Life in general, however, was very contented: people were hardworking and their needs were very few. They led a life of almost ascetic simplicity. Their diet was (and still is) strictly vegetarian. People were deeply religious and, in spite of the lack of worldly goods as we understand them now, particularly in the West, the people were happy. There were no modern medical facilities. People believed in fate and in the will of God and Karma (destiny). This was one of the reasons why centuries of colonialism, exploitation and poverty did not drive people towards Communism. In the villages there were usually one or two people with elementary medical knowledge and the local traditional medicines were very effective in treating all but the more serious illnesses. (In 1955 Meghjibhai was to provide his native village with a small hospital, which serves some eight or ten neighbouring villages).

The caste system in India is as ancient as Mount Everest. In each village there were about half a dozen houses of Brahmins (the priestly caste) and a number of houses of the merchant class who were called Banias. The Visa Oshwals, who today make up about 30% of the population of Meghjibhai's native village, are a well-respected Bania caste (though they were commonly engaged in farming). There would be a fair number of families of farmers and there would also be manual labourers who worked on the farms or in other manual jobs. There would normally be artisans essential to the life of the largely self-contained village community, carpenters, blacksmiths, potters, masons and the like. Each family followed its own hereditary vocation. There was also the unfortunate class of Harijans (who used to be called 'untouchables') who were treated as outcastes and did the menial work of sweeping the streets and cleaning the latrines.

The British Raj was a law and order government and they certainly enforced it very effectively, even if ruthlessly at times. Dabasang was in the princely state of Jamnagar with its capital in the nearby town of that name. The very famous cricketer Ranjitsinhji became Maharaja (or Jamsaheb) of the state in 1907 when Meghji was still a little boy. The British government very rarely interfered in the governments of the Indian rulers. At one time, the whole country belonged to the Indian rulers known as Maharajas, Nawabs (after the Moghul invasion), Rajas or by other titles. Two thirds of it was swallowed up by the British colonial power by conquest. The condition of the people in the princely States varied considerably. However, in most States the ruler was looked upon as a father to the people and he would be responsive (with a few exceptions) to the needs of the people in times of famine and trouble. But there were some black sheep also. Some States were islands of progress and the condition of the people better than in British India. In the State of Gondal and Morvi in Kathiawar, for instance, roads and schools were constructed in most of the villages, whilst medical facilities and telephones were available all over the State's territories. In some of the States the rulers were really worshipped. The historical situation was that after the conquest of India by the British, most of the princes had entered into treaties acknowledging the suzerainty of the British and were more or less independent for internal administration. In the village of Dabasang the local squire (the landowner) was Joravarsinhji by name, a near relation of the Jamsaheb of Jamnagar State.

In some cities modern industry was growing slowly. In Bombay and Ahmedabad the new cotton mills were to be seen, often developed by Jain entrepreneurs. Some large modern ports provided a route for overseas trade. But rural India was untouched by these developments: in general, throughout the land, the small craftsmen in their tiny workshops supplied the needs of the locality as they had done for centuries.

This was the high noon of the British Raj. The British Empire had expanded across the world: it was a proud boast that the sun never set on that Empire. In India, English education and culture were seized upon avidly by many young people. Government service offered a highly sought career, though the highest posts remained reserved for the expatriates from Britain. But western education, indeed any education at all, was the privilege of a very few. Fortunate indeed was the village which could boast a school where local boys could get an education at least of primary school level.

With western education, even on such a limited scale, came political awakening. The desire for freedom and nationhood had spread from Europe to Asia, and in India the leaders of the Indian

National Congress were arousing the consciousness of the educated classes and launching the freedom movement in all parts. But progress was slow. In the hundreds of semi independent states, large and small, which made up a great part of the sub-continent, the local rulers, kings and rajas and princes, were well content with British rule. The British Raj had brought peace and protection. Certainly there were occasional instances of autocratic and even tyrannical imperialism but the fear of the British government gave the people of the princely states security against uncontrolled maladministration.

Dr. Paul Marett

Dr. Paul Marett