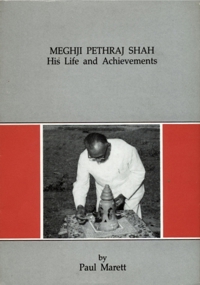

In the same year as the Thika factory opened there was a stroke of good fortune. A similar factory under the European ownership of the Bakau and Kenya Company had already been operating at Limuru on a 15 acre site but the owners had closed it down. Once the Thika factory was under way Meghjibhai turned to ways to expand the project. The Limuru factory offered an obvious opportunity and he set his mind on acquiring it. There was one difficulty: Asians were not permitted to buy land in the highlands where the government was bent on encouraging development of the estates owned by white settlers. There was a way around this. A company was formed with Mr. W. E. Pritchard, the engineer at the Thika factory I and Major Stretton, of the Nairobi law firm of Delaney and Stretton, as directors. (Mr. Pritchard had formerly been with the Natal Extract Company but offered his services to Meghjibhai when differences arose with his employers.) Negotiations were started with the other company. As they were not interested in starting the factory up again Meghjibhai was able to strike a hard bargain and acquired the factory (through the nominee company) in 1934. Once the deal was completed, Mr. Pritchard and Major Stretton transferred the shares into the control of Meghjibhai and Premchandbhai (either to them personally or to Premchand Raichand and Co.: at this distance of time it is not possible to determine the exact arrangement). Around the same time, a wattle farm or plantation at Limuru was bought, this time through Premchand Raichand's export agents, the German company of A. Baumann. These transactions, by-passing the law on the sale of land to Indians, aroused uproar amongst the white settlers and the government in fact passed a law to prevent repetition.

At any rate, the new factory was re-opened and full production was soon under way. Meghjibhai was not, of course, directly engaged in the day-to-day administration of the factories, which was in the hands of managers, but he did keep a close eye on their operation. The manager at the Thika factory was Mr. Raishi Rupshi Shah. Although there were two separate companies, Kenya Tanning Extract Limited and Limuru Tanning Extract Company Limited, they formed effectively one large business. In the first few years there was intense competition with the Natal Tanning Extract Company. Negotiations took place between Premchand Raichand and the Natal Company and in 1937 they formed a trade association to co-ordinate their operations in their common interest, with the approval of the government. Expansion was not without its problems. Running two factories meant twice the work. Moreover sales had to be raised to keep pace with the increased output. Next year Meghjibhai toured Japan and other Far Eastern countries on a sales drive. His tour was successful and he found more customers: he ensured that these new buyers were financially sound before he took their orders. It does seem, indeed, that he had considerable talent on the marketing side, though he had a good product and one for which there was a world demand.

By now Meghjibhai had spent quite a long time in Thika getting the tannin extract business under way. Both factories were thriving and he felt that he could now leave them in the hands of Premchandbhai and his partners, releasing him to plan new ventures. In fact Meghjibhai' s absence was followed by a downturn of business. Exports decreased and the factories found themselves holding large unsold stocks. It seemed that Meghjibhai's guiding hand on the reins was needed again, at least for the time being. Since he had started up this industry, Meghjibhai felt that he had a responsibility to keep it running and he was persuaded to take over the direction again. He introduced improvements in the management and brought the business back on an even keel. He followed this up with a trade visit to England where he was successful in obtaining considerable orders from British importers. Around this time he also visited Romania to sort out certain problems, which had arisen in relation to the trade in tannin extract. (The visit was not connected with the petroleum imports from Romania in which he was also engaged before the war).

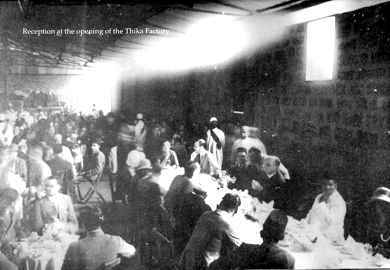

Now both factories, at Thika and Limuru, were running well and they continued to progress for several years. However, by 1944, the pace began to slacken. With the considerable demand for bark it is not surprising that the bark producers, finding themselves in a sellers' market, were tempted to raise their prices for the essential raw material. The higher prices affected the profitability of the factories. Meghjibhai reasoned thus: 'if we do not satisfy the producers of bark we shall not get their co-operation, and we depend on them for supplies. If we want to acquire wealth for ourselves we should first distribute a proportion of our gains to the primary producers and then take our own reasonable share. If we keep our suppliers satisfied, our trade will flourish. So, we must look elsewhere for the necessary economies'. Meghjibhai had thought this through carefully and planned where cuts in expenditure could be made. Running two factories at two different locations was an expensive and inefficient method bearing in mind the volume of production. So, production should be concentrated at one factory and with the installation of the most up-to-date machinery the output of that one factory would be as great as that of the two combined. His partners were immediately convinced and plans for their merger were put in hand at once. The factory at Limuru was closed and the pieces of machinery, which would be of use in the newly expanded plant, were transferred to the Thika factory. The factory premises and the farm at Limuru were sold to a company called Gardens and Plants. Orders were placed at once for other modem machines. As the chemicals extracted from the wattle bark are corrosive of steel much of the machinery has to be of copper or brass. Construction of new buildings for the expansion of the factory was started. The factory's own railway siding could take wagons up to fifty tons in weight. By 1947 production at the renovated factory was expanding rapidIy and when reorganisation had been completed production eventually rose to three times that before reorganisation. Output rose to thirty-three tons a day. Meghjibhai' s insight and decisiveness had brought this about.

As an employer, Meghjibhai was always concerned with the welfare of his employees. He knew that a contented workforce, provided with modern conditions and facilities, was the key to a successful business enterprise. In all, 300 people worked in the factory, Indians, Englishmen and Africans. All were provided with furnished accommodation. Ail lived as members of a single large family. In return for good living and working conditions, Meghjibhai expected discipline and commitment from the workforce. He himself kept regular hours. He would be at work punctually and would expect the same punctuality from his employees. If any of his workers fell ill he would visit them and help with medical care and money. He took a deep interest in everybody's welfare but he would not tolerate any sort of slackness.

Mr. Jethalal Kachra Shah, now (in 1988) in his eighty-first year and head of a family with a large timber merchants business and other interests in Thika, can remember the quiet village of Thika in 1929. In 1934 he was employed as a driver by Premchand Raichand and Co. and, beside driving lorries, he acted as chauffeur to Meghjibhai and Premchandbhai on trips all over the country. He remembers Meghjibhai as a true man who insisted on straight work and good results with no idleness. He was a good employer. Even though Jethalalbhai was an employee he was treated as a friend. He would be invited to sit with Meghjibhai at lunch and was generously treated by his employers.

Everybody associated with the factory was proud of it and was prepared to work hard to keep the business well to the forefront. This was the only enterprise of its kind in the world which was in Indian ownership: Meghjibhai and his partners had invested no less than five million shillings capital in it. His faith in the project was fully justified. With the development of the world economy and growing prosperity, particularly in the industrialised countries, the use of leather had increased greatly and the growth of the leather industry entailed, of course, a growing demand for tannin. Not only the countries of Europe but also China and Japan sought the products of Meghjibhai's factory. In the different forms of chopped wattle bark, solid wattle extract and wattle extract powder, the products of the factory at Thika, under the Rhino Brand trade mark, were exported to no fewer than thirty countries. Wattle products still, in the nineteen-eighties, form one of Kenya's principal exports.

To the Kikuyu people the wattle trees are as good as the legendary wish-fulfilling tree, for these trees gave them an income of five million shillings a year from the sale of the bark alone. Before Meghjibhai came to Thika it was only an ordinary village. Besides the native African inhabitants a few Oshwal families had settled there. Meghjibhai certainly had connections there for, perhaps mindful of his own start in life as a village schoolteacher, he founded a primary school in a house in Thika as early as 1923. But the development of the factory at Thika brought growth and prosperity to the village. The factory brought employment and other businesses sprang up to serve the expanding town. The Indians and the Africans living there all shared in the prosperity. Today Thika is a beautiful town. Those who see the schools, the hospital, the club, the swimming pool, the library, the playground and many other modem facilities probably have no idea what all this owes to the visionary genius and practical enterprise of one man, Meghji Pethraj Shah.

Dr. Paul Marett

Dr. Paul Marett