In the Jain canonical works as well as the post-canonical works, we get a long list of the various space-units used to measure the spatial dimensions. Right from the paramāṇu in the microcosmic measurement up to the rajju in the macroscopic (astrophysical) ones, we get the names and measures of these units.

As we have already seen, the ultimate indivisible unit of pudgala is called paramāṇu and the space occupied by one paramāṇu is called one ākāśa-pradeśa (the indivisible space-unit).Thus, the ākāśa-pradeśa can be considered equivalent to the geometrical point.

The ancient canonical works like Bhagavatī and Anuogadārāiṃ are the primary sources dealing in detail this topic. We describe it here. Occasionally, however, we shall also refer to other works[1] like Tiloyapaṇṇatti, Jambuddīvapaṇṇatti, Lokaprakāśa, etc..

The starting point of the description of the space-units is the paramāṇu (the ultimate atom) of pudgala. The paramāṇu of pudgala is of two kinds: sukṣma (subtle) and vyāvahārika (empirical). In the present context, the subtle paramāṇu is not intended to be described. An infinite number of subtle paramāṇus make one empirical atom.[2] It cannot be cut or pierced even by the sharpest weapon. For detailed description of such atom, see Anuogadārāiṃ, sūtras 396-399. Abhayadevasūri says that the impossibility of cutting and piercing by any weapon is applicable also to the ultimate (transcendental) atom (naiścayika paramāṇu). Here, however, in the context of the topic of measurement, it is the empirical atom that is intended.[3]

In the Bhagavatī Sūtra, we get the reading of the text as aṇaṃtāṇaṃ paramāṇupoggalāṇaṃ, whereas in the Aṇuogadārāiṃ, the reading of the text is-"aṇaṃtāṇaṃ vavahāriya paramāṇupoggalāṇaṃ". Abhayadevasūri explains paramāṇu (given in Bhagavatī's readings) as an empirical atom. The following table provides a comparison of the Bhagavatī and Aṇuogadārāiṃ texts on the topic:

| Bhagavatī, 6/134 | Aṇūogadārāiṃ, Sūtras 399, 400 |

| Infinite material atoms = 1 utślakṣṇaślakṣṇikā[4] | Infinite number of empirical (practical) atoms = 1 utślakṣṇaślakṣṇikā |

| 8 utślakṣṇaślakṣṇikās = 1 ślakṣṇāślakṣṇikā[5] | 8 utślakṣṇaślakṣṇikās = 1 ślakṣṇāślakṣṇikā |

| 8 ślakṣṇāślakṣṇikās = 1 ūrdhvareṇu[6] | 8 ślakṣṇāślakṣṇikās= 1 ūrdhvareṇu |

| 8 ūrdhvareṇus = 1 trasareṇu | 8 ūrdhvareṇus = 1 trasareṇu |

| 8 trasareṇus = 1 rathareṇu | 8 trasareṇus= 1 rathareṇu |

| 8 rathareṇus = 1 bālāgra of theDevakuru and Uttarakuru humans[7] | 8 rathareṇus = 1 bālāgra of theDevakuru and Uttarakuru humans |

| 8 bālāgras of the Devakuru andUttarakuru humans = 1 bālāgraof Harivarṣa-Ramyakvarṣa humans[8] | 8 bālāgras of the Devakuru and Uttarakuru humans = 1 bālāgra of Harivarṣa-Ramyakvarṣa humans |

| 8 bālāgras of the Harivarṣa-Ramyakvarṣa humans = 1 bālāgra of Haimavata-Hairaṇyavata humans[9] | 8 bālāgras of the Harivarṣa-Ramyakvarṣa humans = 1 bālāgra of Haimavata-Hairaṇyavata humans |

| 8 bālāgras of the Haimavata- Hairanyavarta[10]humans = 1 bālāgra of the Pūrvavideha-Aparavideha[11] humans | 8 bālāgras of the Haimavata-Hairanyavarta humans = 1 bālāgra of the Pūrvavideha- Aparavideha humans |

| 8 bālāgra of the Pūrvavideha-Aparavideha humans[12] = 1 likṣā | 8 bālāgras of the Pūrvavideha-Aparavideha humans = 1 bālāgra of the Bharata-Airāvata[13] humans |

| 8 bālāgras of the Bharata-Airāvata humans = 1 likṣā | |

| 8 likṣās = 1 yūkā | 8 likṣās = 1 yūkā |

| 8 yūkās = 1 yavamadhya[14] | 8 yūkās = 1 yavamadhya |

| 8 yavamadhyas = 1 aṅgula | 8 yavamadhyas = 1 utsedha aṅgula |

| 6 aṅgulas = 1 pāda | 6 aṅgulas = 1 pāda |

| 12 aṅgulas = 1 vitasti | 12 aṅgulas = 1 vitasti |

| 24 four aṅgulas = 1 ratni | 24 four aṅgulas = 1 ratni |

| 48 aṅgulas = 1kukṣi | 48 aṅgulas = 1kukṣi |

| 96 aṅgulas = 1 daṇḍa, dhaṇūṣa, yuga, | 96 aṅgulas = 1 daṇḍa, dhaṇūṣa, yuga, |

| nālika, akṣa, musala | nālika, akṣa, musala |

| 2000 dhaṇūṣas = 1 gavyūta | 2000 dhaṇūṣas = 1 gavyūta |

| 4 gavyūtas = 1 yojana | 4 gavyūtas = 1 yojana |

Further,

asaṃkhya yojanas = 1 rajju (see, supra pp. 159-167).

7 rajjus = 1 jagaśreṇī.[15]

It may be useful to know the space-units as mentioned in other ancient traditions and also to compare the Jain space-units with them as well as modern space-units.

In the Buddhist work named Lalitavistara,[16] we get the following space-units:

| 7 Paramāṇu-raja 7 Reṇu 7 Truṭi 7 Vātāyana-raja 7 Śaśā-raja 7 Eḍaka-raja 7 Go-raja 7 Likṣā-raja 7 Sarśapa 7 Yava 12 Aṅguli-parva 1 Vitasti 4 Hasta 1000 Dhanu 4 Krośa | 1 Reṇu 1 Truṭi 1 Vātāyana-raja 1 Śaśā-raja 1 Eḍaka-raja 1 Go-raja 1 Likṣā-raja 1 Sarśapa 1 Yava 1 Aṅguli-parva 1 Vitasti 1 Hasta 1 Dhanu 1 Krośa (Kośa) 1 Yojana |

Now, when we compare these space-units with the Jain space units, we find that there is complete agreement between those units which are between aṅgulī-parva and dhanu, except that we get the name aṅgula in the Jain units. Again, whereas 2000 dhanuṣas are equal to 1 kośa (gavyuta) in the Jain units, we get 1000 dhanuṣas=1 kośa in the Buddhist units

It means that

1 yojana = 7,68,000 aṅgulas in the Jain tradition.

1 yojana = 3,84,000 aṅgulīparvas in the Buddhist tradition.

Thus, 1 aṅgula (in the Jain tradition) = 2 aṅgulīparvas (in the Buddhist tradition).

The Buddhist space-units have been converted into the modern space-units.[17]According to Dr. Bibhuti Bhushana Datta,

1 paramāṇu -rajja = 1.3 x 7-10inches

Now, since 1 aṅgulīparva = 710 paramāṇus

1 aṅgulīparva = 1.3 inches

Thus, 1 aṅgula = 0.65 inches

Now, 1 yojana = 7,68,000 aṅgulas= 7,68,000 x 0.65 inches

= 499200 inches

and... 1 mile = 63360 inches, we get

1 yojana = 499200/63360 miles

= 7.8787 miles approximately.

If we take 1 aṅgulīparva to be 1.32 inches, then we get 1 yojana to be 8.00 miles.

This is corroborated by the traditional belief which considers1 kośa = 2 miles.[18] We can thus consider the yojana based on utṣedhāṅgula to be equal to 8 miles.

In the Śvetāmbara tradition, the yojana based on the paramāṇaṅgula is used to measure astrophysical distances like the diameters of the oceans, continents etc., where

1 paramāṇaṅgula = 1000 utṣedhāṅgula

whereas in the Digambara tradition

1 paramāṇaṅgula = 500 utṣedhāṅgula.[19]

Thus, in Śvetāmbara tradition,

1 yojana = 8000 miles

In Digambar tradition,

1 yojana = 4000 miles.

In the next appendix, we shall discuss about the time-units in the Jain tradition. There we shall see how the units like utṣedhāṅgula and bālāgras (hair-tips) of the humans of Devakuru and Uttarakuru regions are used to calculate the time-units. Here also there is difference in the values of utṣedhāṅgula.

In the Shvetambara tradition,[20]

1 utṣedhāṅgula = 87 bālāgras of the Uttarakuru and Devakuru humans.

In the Digambara tradition,

1 utṣedhāṅgula = 87 bālāgras of the Uttama Bhogabhūmi humans.

We have considered in the above list the space-units of one dimensional extension. Now we consider the two dimensional space-units.

There are two space-units of two-dimensional measurements:[21]

1 pratarāngula = (suci-aṅgula)2

1 jagapratara = (jaga-śreṇī)2

There are four space-units of three-dimensional measurements:[22]

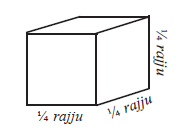

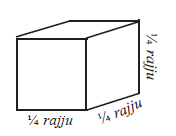

(1) khaṇḍuka: The cube (solid body having six equal square sides) with all sides measuring ¼ rajju is called a khaṇḍuka (See figure). Thus,

1 khaṇḍuka = 1/64 cubic rajju

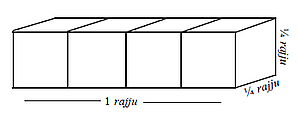

(2) Sucī rajju : Four khaṇḍukas placed in a straight line is called sucī rajju. (See figure).

Its dimensions are 1 rajju, ¼ rajju and ¼ rajju respectively. Thus,

1 sucī rajju = 4 khaṇḍukas

= 1 x ¼ x ¼ cubic rajju

= 1/16 cubic rajju.

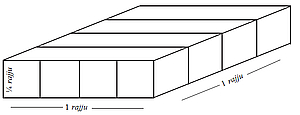

(3) Pratara rajju : the four sucī rajjus placed in a single plane forming a cuboid having dimensions of 1 rajju, 1 rajju and ¼ rajju respectively. (See figure)

1 pratara rajju = 4 sucī rajjus

= 16 khaṇḍukas

= 1 x 1 x ¼ cubic rajju

= ¼ cubic rajju.

(4) Ghana rajju : The four pratara rajjus placed to form a cube fo dimension of 1 rajju each. (See figure)

1 ghana rajju = 4 pratara rajjus

= 16 sucī rajjus

= 64 khaṇḍukas

= 1 cubic rajju.

In the Digambara tradition, we get the following two space units in three dimensional measurements:[23]

1 ghanāṅgula = (suci- aṅgula)3

1 ghanaloka = (jagaśreṇī)3

Bhagavatī, 6.134; Aṇuogadārāiṃ, sūtras 388-400; Jambuddīvapaṇṇatti, 2.6;

Lokaprakāśa, 1.21-67; Tiloyapaṇṇatti, 1.95-116.

Bha. Vṛ. 6.134-yadyapi ca naiścayikaparamāṇorapīdameva lakṣaṇaṃ

Tathā'pīha pramāṇādhikārādvyāvahārikaparamāṇulakṣaṇamidamavaseyam.

In its place, in Tiloyapaṇṇatti, we get 'uvasannāsana skandha' and in Jambuddīvapaṇṇatti we get 'ussaṇha saṇhiāi'.

In its place, in Tiloyapaṇṇattiī, we get 'sannāsana skandha' and in Jambuddīvapaṇṇatti we get 'saṇhasaṇhiyāi'.

Aṇu. sū. 418-432.-In the original text of Bha., we get the reading eraṇṇavayāṇaṃ, but in Ṭhāṇaṃ and Anu., we get heraṇṇavayāṇaṃ

In the original text of Bha., we do not get the reading aparavideha, which, it seems, is erroneously omitted.

In the Śvetāmbara tradition, the term jagaśreṇī is not mentioned. However, at some places the term abhrāṃśaśreṇī is found. (See, Lokaprakāśa, 12.136)

See Hindu Gaṇita-śāstra Kā Itihāsa, by Dr. Bibhuti Bhusana Datta and Dr.

Avadhesa Narayana Singh, Hindi Edition, p. 177.

Prof. Muni Mahendra Kumar

Prof. Muni Mahendra Kumar