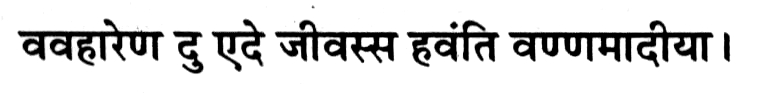

vavahāreṇa du ede jῑvassa havaṃti vaṇṇamādῑyā.

guṇaṭhāṇāṃtā bhāvā ṇa du keῑ ṇicchayaṇayassa.. 18

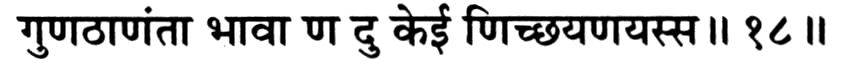

edehi ya saṃbaṃdho jaheva khῑrodayaṃ muṇedavvo.

ṇa ya huṃti tassa tāṇi du uvaogaguṇādhigo jamhā.. 19

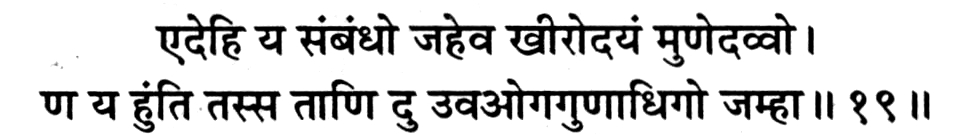

paṃthe mussaṃtaṁ passidūṇa logā bhaṇaṃti vavahārῑ.

mussadi eso paṃtho ṇa ya paṁtho mussade koῑ... 20

taha jῑve kammāṇaṃ nokammāṇaṃ ca passiduṁ vaṇṇaṃ.

jῑvassa esa vaṇṇo jiṇehi vavahārado utto.. 21

gaṃdharasaphāsarūvā deho saṃṭhāṇamāiyā je ya.

savve vavahārassa ya ṇicchayadaṇhū vavadisaṃti.. 22

(Ede) Those [aforementioned] (vaṇṇamādῑyā. guṇaṭhāṇāṃtā bhāvā) attributes, from colour to stages of spiritual advancement (called guṇasthāna) belong to the soul from the empirical aspect only, (du) but (ṇicchayaṇayassa keῑ ṇa) none of them does so from the transcendental aspect.

(Ede hi ya saṃbaṃdho) The relationship of these attributes with the soul (mūnedavvo) is to be regarded (khῑrodayaṃ jaheva) as milk with water; (ya) moreover (tāṇi tassa du ṇa hoṃti) they (i.e. attributes) could not belong to the soul (jamhā) because (uvavoga guṇādhigo) the soul is replete with (its own attribute) consciousness.

(paṃthe mussaṃtaṃ passiduṇa) On seeing somebody being robbed on the road (vavahārῑ logā bhaṇaṃti) people, conventionally, describe this phenomenon by saying that (eso paṃtho mussadi) 'this road is being robbed but (koῑ paṃtho ṇa ya mussadi) it is not the road which is being robbed (but the traveller using the road who is being robbed)'. (Taha) Similarly, (jῑve kammāṇaṃ nokammāṇaṃ ca passiduṃ vaṇṇaṃ) perceiving the color [and form] of the kārmaṇa body and the physical body associated with the soul, (jinehi vavahārado utto) Jinendra Deva makes a conventional pronouncement that (Jivassa esa vaṇṇo) this color is that of the soul. In the same way the pronouncement about all other attributes (gaṃdhā-rasa-phāsa-rūvā deho saṃṭhāṇamāiyā savve ya) smell, taste, touch, form, body and configuration etc. (vavahārassa ṇicchayadaṇhū vavadisaṃti) belonging to the soul is made conventionally by the seer of the ultimate aspect, i.e., the omniscient himself.

Annotations:

The worldly existence of the soul is the result of interaction between the self and the non-self and their close association (bondage). Apart from the gross or physical body, there is a subtle body composed of very fine karmic matter. In the state of bondage, the soul is infected with a tendency to attract the karmic matter which can mix with the soul much in the same way as milk mixes with water. This tendency or susceptibility, called bhāva karma, finds expression in psychological distortions (emotions and passions). In the ultimate analysis this susceptibility is but a state of the soul in bondage with karmic matter called dravya karma. Thus a distinction is to be made between the material dravya karma and its concomitant counterpart—psychological bhāva karma. They are mutually related as extrinsic cause and effect each of the other.

Although there is concrete identity between the non-material soul and the material body in the worldly state of existence, the two are ultimately different, being two different eternal substances. The former view viz. the concrete identity is the empirical or vyavahāra aspect while the latter i.e., the difference is the transcendental or niścaya aspect. All the characteristics of matter viz. colour, odour, taste and touch are assessed by the karmic as well as the gross physical bodies, and hence, they can be said to belong to the soul only from empirical or conventional view and not from the ultimate view.

It has been stated above that karmic matter mixes with the soul much in the same way as milk mixes with water. Now, when seen with naked eyes, milk APPEARS to be homogeneous white liquid, but when viewed through a microscope a drop of milk is seen to be a heterogeneous mixture with tiny blobs of fat floating in water. Thus, in the milk, fat and water remain separate although apparently unified. Moreover by an appropriate process, pure fat in the form of butter can be separated and obtained. Thus fat which is replete with fatness is unaffected by water. Much in the same way, the soul is replete with its own attribute—consciousness—and colour etc. cannot enter and inhere in the soul.

In the above verses, a common analogy is used to reconcile the statements made in the previous verses with the popular aspect of worldly life. In the common parlance it is said that "this road in being robbed". Now everybody knows and understands this statement to mean "a traveller using this road is likely to be robbed". In a similar analogy, when it is asked "where does this road go", the reply is "this road goes to Benares". It is well-known that the "road" never "goes" anywhere and the meaning of the question and answer is well established by convention of associating the road with robbery or a city. Similarly, the association of the karmic and physical bodies (which are material, and hence, possess colour and the like) with the soul establishes the conventional statement that colour etc. belongs to the soul.

The conclusion is that, what is said in the scriptures by the omniscient viz., colour, smell and such other attributes are possessed by the soul, is a conventional truth and not an ultimate one.

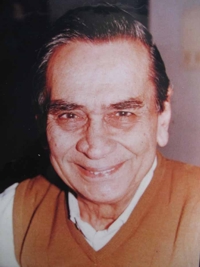

Jethalal S. Zaveri

Jethalal S. Zaveri

Prof. Muni Mahendra Kumar

Prof. Muni Mahendra Kumar