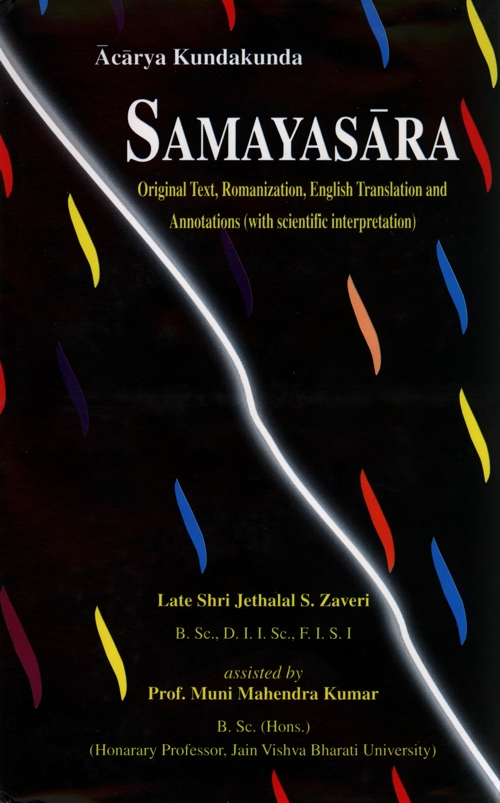

tattha bhave jῑvāṇaṃ saṃsāratthāṇa hoṃti vaṇṇādῑ.

saṃsārapamukkāṇaṃ ṇatthi du vaṇṇādao keῑ..23

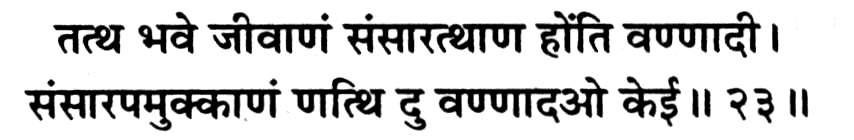

jῑvo ceva hi ede savve bhāva tti maṇṇase jadi hi.

jῑvassājῑvassa ya ṇatthi viseso du de koῑ..24

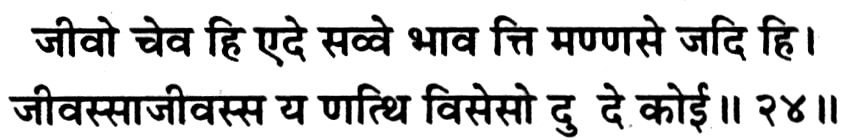

aha saṃsāratthāṇaṃ jῑvāṇaṃ tujjha hoṃti vaṇṇādῑ.

tamhā saṃsāratthā jῑvā rūvittamāvaṇṇā..25

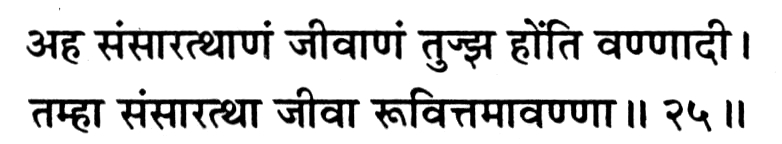

evaṃ poggaladavvaṃ jῑvo tahalakkhaṇeṇa mūḍhamadῑ.

nivvāṇamuvagado vi ya jῑvattaṃ poggalo patto..26

(Tattha bhave) Only in the worldly existence (saṃsāratthāṇa jῑvāṇaṃ) the embodied souls i.e., souls in bondage (vaṇṇādῑ hoṃti) are possessed of colour etc.; (saṃsārapamukkāṇaṃ) the emancipated souls (du kei vaṇṇādao ṇatthi) do not have any colour etc.

Addressing those who (falsely) believe that colour etc. are the ultimate characteristics of the soul, Ācārya says that (Jadi hi tti maṇṇase) If you believe that (ede savve bhave) all the aforementioned attributes (jῑva ceva hi) ultimately belong to the soul (du) in that case (de) according to your belief (jῑvassajῑvassa ya viseso ṇatthi) no distinction exists between the soul and the unconscious non-soul i.e. they both become identical.

(Aha tujjha) Again, if according to your belief (saṃsāratthānaṃ jῑvāṇaṃ) unemancipated souls in worldly life (vaṇṇādῑ hoṃti) are absolutely possessed of colour etc. (tamhā) if that is so (saṃsāratthā jῑvā) souls in worldly life (ruvittamāvaṇṇā) would become rūpῑ (that is assume material form).

(Evam) So, (mūḍhamadῑ) oh, you ignorant one! (tahalakkhaṇeṇa poggaladavvaṃ jῑvo) matter is being identified with the soul because material form (rūpatva) is a characteristic only of matter (pudgala), (ya) and (ṇivvāṇamuvagado vi) finally when emancipated (poggalo jῑvattaṃ patto) the unconscious matter has become conscious (jῑva).

Annotations:

In these verses, firstly, it is conceded that in the worldly state of existence the souls are not disembodied and, therefore the attributes colour, smell etc., which are always possessed by the physical bodies only may be conventionally expressed as being possessed by the soul. This is because in the worldly life, the body and the soul are presented in real experience, as a unity called organism. But it must be borne in mind that when any soul is emancipated, it is pure soul without body or any other material encumbrance and, therefore, without any of these attributes. This, therefore, should leave no doubt that the statement "the soul possesses colour etc." is only an empirical or conventional expression.

In spite of this clear position, some may persist in believing that they are permanent attributes of the soul. Admonishing such a die-hard absolutist, author says-"If you believe that all attributes of matter are ultimately possessed by jῑva also, then we, inevitably come to an absurd conclusion that there is no distinction between the conscious substance—jῑva and unconscious substance—matter."

Expounding his argument further, author reaches a more drastic and ridiculous conclusion that matter is transmuted into jῑva. He further argues—"If, according to your belief, souls in worldly state are possessed of colour, smell etc. in an absolute sense, they would become rūpῑ, i.e., they would permanently assume a material form. Now it is well known and universally accepted that rūpatva—material form is a characteristic only of one of the six eternal substances, viz., matter (pudgala). Now as and when these rūpῑ souls (as per your belief) become emancipated, which they would, undoubtedly be, if they follow the prescribed path of spiritual discipline, then in that case, there is only one conclusion that matter has been transmuted into jῑva who has been emancipated."

Thus, asserts the author that regarding a conventional statement to be an ultimate truth is erroneous and the fallacy may lead to unacceptable and absurd situation. Colour, smell and the like must never be regarded as the soul's attributes in an absolute sense.

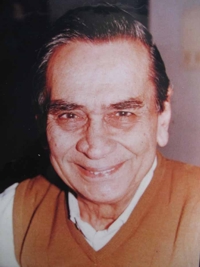

Jethalal S. Zaveri

Jethalal S. Zaveri

Prof. Muni Mahendra Kumar

Prof. Muni Mahendra Kumar