The essay was first published in April 1976 in the periodical Jain Journal and has been reissued later in the miscellany volume Jainthology (Ed. by Ganesh Lalawani, Calcutta: Jain Bhavan, 1991).

Jainas as a Minority in Indian Society and History

Jainas are the sixth most numerous religious group today after the Hindus (82.72%), Muslims (11.21%), Christians (2.60%), Sikhs (1.89%), and the Buddhists (0.70%). The Jainas (0.47%) along with the Buddhists, Parsis and Jews, each account for less than 1% of India's total population separately. (India 1974: 13) In terms of numbers alone, therefore, the Jainas constitute a very small minority (Census of India 1961, Vol. XV, Uttar Pradesh, Pt. I-A (ii): 115; India 1974: 12).

Scholars have long raised questions regarding the accuracy of census figures but it is generally accepted that more than any other group the Jainas have been very much at fault in misrepresenting their religious affiliation (for whatever reason) to census takers. This was noticed even in 1915 (Stevenson: 20) and continued until recently (Sangave 1959: 1). Many thousands of Jainas still register themselves as Hindus. Thus, it would seem that the actual number of Jainas is somewhat larger than the census figures would indicate; still it would not substantially alter their status as an extremely small minority. The 1971 census reports that there were only 2,604,646 (i.e., 0.47%) Jainas out of India's total population of 547,949,809. Even allowing for misrepresentations, their population in India would not amount to more than three million at the most.

If we consider the Jaina population figures in the record of the last ten censuses, we notice that the Jainas constituted only 0.49% of the total population in 1891 (the highest ever since census figures began to be collected in 1881) and merely 0.36% (the lowest ever) in 1931. [1]

Throughout the entire past century Jainas officially accounted for less than onehalf per cent of the total population. Their growth rate has greatly varied, from the lowest decrease of—6.4% in 1901-1911, to the highest rate of growth of 28.48% during the last decade, and their population has more than doubled between 1881 to 1971 (1,221,896 to 2,604,646). Yet their overall strength in the total population has, in fact, declined, (cf. Sangave 1959: 1-46; India 1974 : 12-13). [2]

Jainas are found all over India and are mainly concentrated in the western and central regions. The largest concentration of Jainas at present is to be found in Maharashtra (703,664), Rajasthan (513,548), Gujarat (451,578), Madhya Pradesh (345,211) and Karnataka (former Mysore; 218,862) while there are 124,728 Jainas in U.P. (and 50,513 in Delhi). Only in these six States do the Jainas account for more than 100,000 each, along with a sizeable population in the capital. But the Jainas are found even in the remotest corners of India, e.g., three are noted in Mizoram between Bangladesh and Burma, fourteen in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands and thirty-nine are in the former North-East Frontier, now called Arunachal Pradesh. Only in the Union Territory of Lakshadweep, west of Kerala in the Indian Ocean, were no Jainas recorded for the 1971 census (cf. Table 1.10 in India 1974: 12).

Jainas live mostly in big cities and towns and it can be said that "the Jaina community is essentially urban in character" (Sangave 1959: 5). [3] Yet another significant fact about their distribution pattern that can be drawn from pre-Independent India Census figures in that the Jainas preferred to live in Princely States and Agencies as opposed to the Provinces of British India. In 1901, 64% of the Jainas lived in Indian India, while only 36% settled in the British ruled Provinces; while the figures for 1941 show 60% and 40% respectively (Sangave 1959: 3-4).

A third significant point about Jaina population distribution is that they have been heavily concentrated in the Hindu dominated areas and only sparsely spread in the regions dominated by the Muslims. In Sangave's opinion, as Jainism is closer to Hinduism than to any other religion in India this might have resulted in the Jainas choosing the Hindus as their neighbours. Lastly and surprisingly, the land where Mahāvīra wandered and preached during his lifetime is scarcest in Jaina population. (Sangave 1959: 3-4). It seems evident, in the light of sources available, that in the post-Mahāvīra days (i.e., after c. 500 B.C.), a section of the Jaina community moved to western and central India via Mathurā, while another section went directly to the Karnataka region sometime during the 4th century B.C. (cf. Shah 1932; K. C. Jain 1963; Desai 1957; Deo 1952).

It seems that Jaina influence and concentration shifted in the course of time, but it is difficult to imagine their numerical strength ever being more than one per cent of India's total population at any given point in history. It was noticed above that despite there being no change in their percentage in the population there was a noticeable decline within Jaina population as a whole. According to Sangave the factors like the deficiency of females, practice of early marriage, low fertility of women, high rate of female mortality, large numbers of unmarried males and great proportion of young widowed females effectively barred from remarriage, have all combined together to lower the growth of Jaina population (Sangave 1959: 414). To this he adds the lack of proselytizing activities of the Jainas (at least since medieval times) as well as thousands of Jainas leaving the faith every year. (Ibid.: 414-15) But in my view Jaina ethics and discipline are too demanding, the community pressure and conservatism so great that it does not appeal to the non-Jainas, while many Jainas are driven to other creeds.

Jarl Charpentier says much the same thing about Jainism though he choose to emphasize other aspects. According to him "the Jain church has never had a very great number of adherents; it has never attempted - at least not on any grand scale - to preach its doctrines through missionaries outside India. Never rising to an overpowering height but at the same time never sharing the fate of its rival. Buddhism, that of complete extinction in its native land, it has led a quiet existence through the centuries and has kept its place amongst the religious systems of India till the present day" (Charpentier 1935: 169-70).

Jainas in History and Society

The Jainas are strictly an Indian phenomenon. They are not found elsewhere. Some Jainas might well have migrated to and settled down for a while with neighbouring countries of Nepal and Sri Lanka, but they have not accounted for more than temporary residents in historical terms. Therefore, when we speak of their role in history and society, we mean, their role in Indian history and society. The Jainas claim to be the oldest living religious community in India. While contemporary historians would basically agree with this view, they also would assign a similar antiquity to the Hindus. It is now generally accepted that Jainism is at least two centuries older than Buddhism and some of its elements might well be traced to the Indus Valley civilization of the third millenium B.C. (cf. Williams 1966: 2-6; Zimmer 1956: 181-204) Jaina doctrines, mythologies and practices reveal that, having lived a long and continuous existence within the vastly dominant Hindu population, they have been immensely influenced by the latter. Yet they have managed to retain identity and continuity of a separate community. Moreover, the Jainas felt a particular sense of competition and rivalry with the Ājīvikas and Buddhists. The rigorous commitment of the Jainas to the ascetic ideal, persistent adherence to the principle of non-injury (ahiṁsā) and closeknit community organization served them in good stead and they not only outlived, but also outdid their rivals.

I believe that it is primarily because of these three characteristics that Jainas have held their own and occupied an important position in Indian society, despite a minuteness of numbers. They seem to have wielded a greater political, cultural, economic, artistic and moral influence in India than expected. In fact, Jaina contributions in these areas are not only much larger in terms of time (or duration) but also greater in proportion to those of the larger minorities of Sikhs and Christians. Their overall impact on Indian society and history is also much greater than those of the Parsis and the Jews and in this they vie for comparison with much larger Muslim minority and more widely discussed one of the Buddhist.

Jainism is a religion of great antiquity which first flourished in eastern India in the region of Banaras and Bihar. It has a recognized series of 24 Jinas or teachers, their own canons and a well-organized body of monks and lay community that has existed through the centuries, (cf. J.L. Jaini 1916; Stevenson 1915) Two of the last great Jinas, Pārśva and Mahāvīra, lived and preached in the 8th and 6th centuries B.C., respectively. Mahāvīra's family already professed Pārśva's doctrines; he himself renounced his worldly ties when he was about thirty years old, after meeting his family obligations and taking due permission of his elder brother. He did not run away like Gautama Buddha at dead of night leaving his wife and child uncared for. He searched for the truth for about twelve years, meditated and practised severe austerities through which he came to understand and fully control his feelings and passions. He became fully aware and fearless like a lion, he became the perfected one. He became the Jina, "conqueror" of feelings and passions (equivalent to the Buddha as "the enlightened one") and could now go and preach his path, a path which unlike that of the Buddha, was not a new one. This was the same path that Pārśva had preached about 250 years earlier and 22 Jinas before Pārśva. Mahāvīra claims no originality for his doctrines. He reformulated the system which already existed and there were other followers of Pārśva even before Mahāvīra became a Jina and main spokesman for the Nigaṇṭhas as the Jainas were known in the 6th century B.C. Mahāvīra, however, more heavily emphasized the ascetic rules for the monks than had Pārśva. Mahāvīra may have noted the moral laxities found in contemporary monks whether Jaina, Ājīvika or Buddhist. He set an unusually high standard of ascetic morality which has led many an earlier student of Indian philosophy and religion to regard him as an originator of a new system.

Jainas enjoyed the support and patronage of contemporary kings like Ceṭaka of Vaiśālī, Śreṇika (Bimbisāra) and Kuṇika (Ajātaśatru). Later on the Mauryan emperors Candragupta and Aśoka also patronized them as did the "Jaina King" Kharavela of Kalinga. It is also certain that a number of prominent merchants and aristocrats and nobles also showed their appreciation for Jainism during the pre-Christian era. It was apparently in the days of Candragupta Maurya (4th century B C.) that a section of the Jaina community moved south under the leadership of Bhadrabāhu. The emperor Candragupta Maurya himself is said to have renounced his throne under the impact of this great Jaina ascetic and accompanied his followers to Karnataka (Mysore). This migration is said to have been caused by a twelve-year famine. While still in the south Candragupta is said to have fasted to death in the true Jaina manner.

Western India though an important Jaina stronghold from the days of Kumārapāla and his Jaina counsellor Hemacandra in the 12th century A.D., it has had a Jaina community for several centuries. The last great council to settle canonical differences was held in this region (at Vallabhī) in the 5th century. There is even the tradition of Nemi (the 22nd Jina and contemporary of Kṛṣṇa) having attained kaivalya on Mt. Girṇār in Gujarat. Historically, at any rate, Jainism can be traced back to around 2nd century B.C. in the western region. (K. C. Jain 1963; Sheth 1953) Sufficient evidence has also come to light that shows that even earlier in the 3rd century Jainism had an important place in Mathurā, the famous city on river Yamunā associated with the boyhood of Kṛṣṇa. Thus, it is easy to conclude that Jainism has had a long history in the western states of Gujarat, Rajasthan and Maharashtra, apart from Mathurā in western U.P. (cf. Shah 1932) In later times, Jainism found a great patron in the Mughal emperor Akbar in the north as well as numerous ruling dynasties in the south (see Sangave 1959: 374-86; Charpentier 1935; Desai 1957; Shastri 1967).

The Jainas built monumental structures, and created great works of art and architecture. No language - old or new, no subject - humanistic or scientific, no philosophical system - orthodox or heterodox, escaped their attention. Jainism initially appealed to the Kṣatriyas and the Vaiśyas in particular, but in course of time only the merchants continued to be their faithful adherents. Through trade and commerce Jainas made a rich and enviable contribution to India's economic growth and well-being and continue to do so to this day. It would not be an exaggeration to state that Jainas have continuously made a rich and varied contribution to India, (cf. H. L. Jain 1962; Nevaskar 1971) Their role in Indian society and history has always been that of a great moral force (from their uncompromising asceticism to Gandhi's non-violence), that of upholders of diversity of thought, cultivators of work and liberation ethic. Moreover, they have been significant contributors to learning and philanthropy, wide-spread and successful trading and money-lending. They have been quietly committed and loyal to the law and authority with a completely clean criminal record. Few minorities can match such a record.

Jaina Attitude towards Other Communities and Ruling Authorities

The very cornerstone of Jaina metaphysics stands on the doctrine of syādvāda, "may-beism", according to which "there is no judgment which is absolutely true, and no judgment which is absolutely false. All judgments are true in some sense and false in another" (Das Gupta 1957: 179). The Jainas are committed to a philosophical position encompassing manifold viewpoints (anekāntavāda), which encourages the cultivation of many schools of thought and expects people to look at any reality or concept from differing viewpoints, (cf. Gopalan 1973: 145-56) With this commitment to the existence of diverse viewpoints and communities, Jainas seem naturally to accept the existence of various minorities in India.

Still, a number of beliefs and practices of the Jainas, betrays the basically conservative character of the Jaina community. [4] This conservatism and the accute sense of the need to survive is more evident from their attitude towards government and authority in general, no matter what its character. The Jainas have had a reputation of being the ideal subjects and citizens throughout their historical existence in India. They have always been a people who took law and order seriously. Whether the power was wielded by a Hindu, Buddhist, Muslim or Christian king or ruler, the Jainas were always ready and willing to accept its legitimacy and authority. [5] They always came forward with whatever help, mainly financial and intellectual, they could offer. [6] This enabled them to establish a quick rapport and smooth working relationship with all manner of government and authority in India. There are many records of Hindu kings extending patronage to the Jainas (e.g. Gupta kings, etc.) as there are of Buddhist kings such as Aśoka, even of some Muslim rulers (like Akbar) and the British government. This loyalty towards ruling authority as such has enabled the Jainas to ply their rich trade and attain immense prosperity throughout their history. It was essentially this loyalty, prosperity and piety that had misled a British missionary to write of them as ideal converts so optimistically and temptingly:

"There is a strange mystery in Jainism; for though it acknowledges no personal God, knowing Him neither as Creator, Father, or Friend, yet it will never allow itself to be called an atheistic system. Indeed there is no more deadly insult that one could level at a Jaina than to call him a nāstika or atheist. It is as if, though their king were yet unknown to them, they were nevertheless all unconsciously awaiting his advent amongst them, and proudly called themselves royalists. The marks which they will ask to see in one who claims to be their king will be the proofs of Incarnation (avatāra), of Suffering (tapā) and of the Majesty of a Conqueror (Jina). But when once, they recognize Him, they will pour out at His feel all the wealth of their trained powers of self-denial and renunciation. Then shall He, the Desire of all Nations, whose right it is to reign, take His seat on the empty throne of their hearts, and He shall reign King of Kings and Lord of Lords for ever and ever" (concluding words of Stevenson 1915: 298).

Jaina Ethics and Occupations

The ultimate goal of the Jainas is the attainment of kaivalya. This is seen as "integration, the restoration of the faculties that have been temporarily lost through being obscured... All beings are intended to be omniscient, omnipotent, unlimited and unfettered... The aim of men must be to make manifest the power that is latent within them by removing whatever hindrances may be standing in the way" (Zimmer 1956: 254-55). These hindrances involve the stoppage of influx of the bad karmic matter that stains the jīva 'life-monad' (known as samvara), and the cleansing of already existing stains on the jīva by producing good karmic matter (known as nirjarā). Under Jainism this goal can only be attained after renunciation and the practice of ascetic life. Thus, the system gives primacy to the monks and only a secondary position to the laity. The monks are expected to live by the five cardinal vows of non-injury, truth, not taking what is not given, chastity, and non-possession (cf. Stevenson 1915: 234-38). The monks were also expected to guide and advise the layfolk towards an ethical and spiritual path. Twelve minor vows were prescribed for the laity which are only a watered down version of the five great vows. [7] Yet the main emphasis was laid on encouraging the lay-folk to take up ascetic life as soon as possible It will be noticed that the principle of non-injury or non-violence occupies a central position both in the life of an ascetic and that of the householder. This has serious implications for the activities and occupations that the Jainas could take up.

Since the Jaina lay adherents were forbidden to injure any living beings, "they might never till the soil, nor engage in butchering, fishing, brewing, or any other occupation involving the taking of life" (Nevaskar 1971: 159). This injunction is regarded by Noss as by far the most important in its social effect. He asserts:

"It constituted a limitation that must have seemed serious to the early followers of Mahāvira; but at long last it actually proved to have economic as well as religious worth, for the Jains found they could make higher profits when they turned from occupations involving direct harm to living creatures to careers in business as bankers, lawyers, merchants, and proprietors of land. The other moral restrictions of their creed, which prohibited gambling, eating meat, drinking wine, adultery, hunting, thieving, and debauchery, earned them social respect..." (Noss 1954: 152 in Nevaskar 1971: 159-60; also see Nakamura 1973: 87).

A Jaina Community survey taken by Sociologist Sangave also showed that though the Jainas follow different kinds of occupations, “they are mainly money-lenders, bankers, jewellers, cloth-merchants, grocers and recently industrialists … “ And in professions “they are mainly found in legal, medical and teaching professions as well as nowadays many Jainas are holding important responsible positions” in various departments of the Union and State governments (Sangave 1959: 279).

The Jainas are a rich and influential minority primarily in commercial activities. J. L. Jaini, writing half a century ago, said that “Colonel Tod in his Rājasthān, and Lord Reay and Lord Curzon after him, have estimated that half the mercantile wealth of India passes through the hands of the Jaina laity. Commercial prosperity implies shrewd business capacity and also steady, reliable character and credit” (Jaini 1916: 73; cp. Weber 1958: 200; Nakamura 197387). Weber also noticed Jaina honesty, wealth, commercial success and their belief in non-violence and found telling comparisons with Parsis, Jews and Quakers. [8]

The above discussion shows that Jaina ethics and their commitment to the principles of non-violence [9] have forced them to follow certain occupations and professions which have led them to unusual success in business enterprises. It is basically their unique ethic that the Jainas, though a small minority community, "developed most of the essentials of the spirit of modern capitalism centuries ago. Now with capitalism entering India from the West, the Jains are unusually well-equipped to play a dynamic role in the social order" of a new India. (Navaskar 1971: 235).

Summary and Conclusions

The Jainas have always constituted a small religious minority of Indian society throughout their historical existence. The two other criteria of language and ethnic background that define a minority do not apply to them for they speak practically every language of India and cannot be isolated ethnically from other Indian people.

An analysis of Jaina population distribution shows their concentration in western India including central India. The Jainas show their preference for urban as opposed to rural areas. They occupy a preeminent position in trade and commerce and much of India's wealth passes through their hands who compose barely ½ % of India's population. Their honesty, reliability, loyalty, integrity and religiosity has won them immense wealth and influence in India. They compare favourably with the peaceloving and pious Quakers and successful and conservative Jews in the West. Their ethic is largely given the credit for this success and sense of loyalty.

Jainism, though preached and propagated by warrior princes (Kṣatriyas), has come to have an entirely merchant (Vaiśya) following. Most scholars have taken this to mean a downward social mobility of the Jainas, i.e., they became nearer to the Śūdras and farther away from the Brāhmaṇas. Yet in the Indian past birth (jāti) alone was never the sole criterion of social status. Wealth, education, life-style, humility and social concern also contributed to social status apart from the criterion of birth. The Jainas, the second most educated people in India after the Parsis, were good and loyal subjects to all governments, largely urban in character and given to many social concerns and philanthropic works. They were proverbially famous for their honesty, humility, wealth and piety. An historical analysis of the ideal qualities and characteristics of each of the four social classes (varṇas) would indicate a close relationship of the Jaina Vaiśyas with the Brāhmaṇas. [10]

When scholars assign a lower status to the Jainas than the Kṣatriyas they seem to be repeating what traditional writers had written milleniums ago. They have neglected to consider the changing reality of Indian society and have ignored the multiplicity of factors that contributed towards social mobility. If interpreted in this light, Indian records furnish sufficient evidence to show that the Vaiśya Jainas have achieved an upward social mobility by most closely paralleling the culture and personality of the Brāhmaṇas. Thus, it can be argued that the Jainas, despite the change in their ascended class (from Kṣatriya to Vaiśya) have by adopting the dominant culture traits of the Brāhmaṇas, raised their social status during the course of Indian history.

Bibliography:

1881 0,48 per cent 1891 0,49 per cent 1901 0,45 per cent 1911 0,40 per cent 1921 0,37 per cent 1931 0,36 per cent 1941 0,37 per cent 1951 0,45 per cent (Sangave 1959: 434) 1961 0,46 per cent 1971 0,47 per cent (India 1974: 13)

1881-1891 1891-1901 1901-1911 1911-1921 1921-1931 1931-1941 1941-1951 1951-1961 1961-1971

Taking India as a whole we find that in 1941, 41.4% of the Jaina population lived in towns, and in Provinces the urban Jaina population was 48.9% and in States and Agencies it was 36.5%. The coresponding figures for all religions were 12.9%, 12.7% and 13.4%. There is a continuous increase in the Jaina urban population in almost all Provinces and States. It would also seem that the Jainas are "more urban in localities, where they are less in number and more rural in areas where they are numerous". It seems generally to be the case that minorities find their way and flourish in cities and towns and that is why "the Jaina commuaity is essentially urban in character" (Sangave 1959: 4-5).

Sangave regards "inflexible conservatism" the very strength of the Jaina community. He writes: "... Another important reason for the survival of the Jaina community is its inflexible conservatism in holding fast to its original institutions and doctrines for the last so many centuries...an absolute refusal to admit changes has been considered the strongest safeguard of the Jainas" (Sangave 1959: 399).

A possible explanation of why the Jainas were ready and willing to accede to new authority and its measures is given in a case reported by J.L. Jaini: "The Indian Penal Code, originally drafted by. Lord Macaulay, takes account of almost all oifences known to and suppressed by our modern civilization. Mr. A. B. Lathe... has shown by a table how the five minor rules of conduct (the five anuvratas of Jainism) cover the same ground as the twenty-three chapters and 511 sections of the code" (Jaini 1916: 72).

Cf. "The royal patronage which Jainism had received during the ancient and medieval periods in different parts of the country has undoubtedly helped the struggle of the Jaina community for its survival... Apart from Jaina rulers many non-Jaina rulers also showed sympathetic attitude towards the Jaina religion" (Sangave 1959: 399).

Twelve minor vows for the layfolk prescribed that he: (1) must not destroy life, (2) must not tell a lie, (3) must not make unpermited use of another man's property, (4) must be chaste, (5) must limit his possessions, (6) must make a perpetual and daily vow to go only in certain directions and certain distances, (7) must avoid useless talk and action, (8) must avoid thought of sinful things, (9) must limit the articles of his diet and enjoyment for the day, (10) must worship at fixed times, morning, noon and evening, (11) must fast on certain days, and (12) must give charity in the way of knowledge, money, etc., everyday (based on Tattvarthadhigama Sutra II: 142-43 in Zimmer 1956: 196, n. 14).

Weber finds striking similarities between the Jainas and the Jews - and calls the former "Jews of the Far East". (Weber 1958: 11) He also notices similarities in "honesty is the best policy" among the Parsis, Quakers and Jainas. Their honesty and wealth were both proverbial. He further adds "that the Jainas, at least the Svetambara Jainas nearly all became traders was due to purely ritualistic reasons... a case similar to the Jews. Only the trader could truly practise ahimsa. This special manner of trading, too, determined by ritual, with its particularly strong aversion against travelling and their way of making travel difficult restricted them to resident trade, again as with the Jews to banking and money-lending" (Ibid: 200).

Apart from the vows the Jaina layfolk were also encouraged to develop the following twenty-one qualities: serious demeanor, cleanliness, good temper, striving after popularity, fear of sinning, mercy, straightforwardness, wisdom, modesty, kindliness, moderation, gentleness, care of speech, socialibility, caution, studious-ness, reverence for old age and old customs, humility, gratitude, benevolence and attention to business (Cf. Nevaskar 1971: 159).

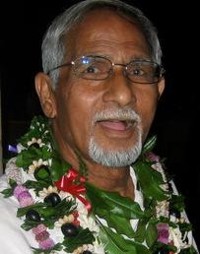

Jagdish Prasad Sharma

Jagdish Prasad Sharma