appaḍikkamaṇaṃ duvihaṃ apaccakhāṇaṃ taheva viṇṇeyaṃ.

edeṇuvadeseṇa du akārago vaṇṇido cedā..47

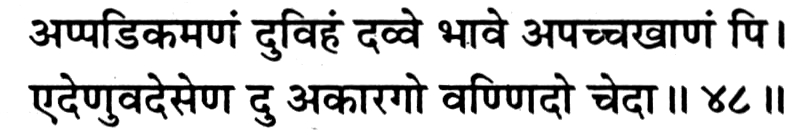

appaḍikkamaṇaṃ duvihaṃ davve bhāve apaccakkhāṇaṃ pi.

edeṇuvadeseṇa du akārago vaṇṇido cedā..48

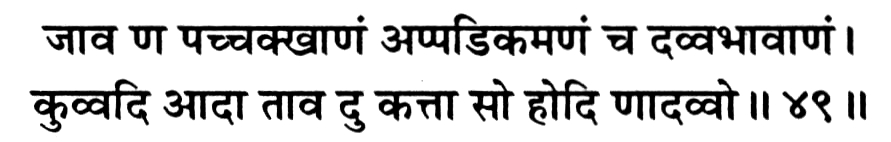

jāva ṇa paccakkhāṇaṃ appaḍikkamaṇaṃ ca davvabhāvāṇaṃ.

kuvvadi ādā tāva du kattā so hodi ṇādavvo..49

ādādkammādῑyā poggaladavvassa je ime dosā.

kiha te kuvvadi ṇāṇῑ paradavvaguṇā du je ṇiccaṃ..50

ādhākammaṃ uddesiyaṃ ca poggalamayaṃ imaṃ davvaṃ.

kiha taṃ mama hodi kadaṃ jaṃ ṇiccamacedaṇaṃ vuttaṃ..51

(Appaḍikamaṇaṃ duvihaṃ taheva appaccakkhāṇaṃ viṇṇeyaṃ) Know that apratikramaṇa and apratyākhyāna are of two types, (edeṇuvadeseṇa du cedā akārago vaṇṇido) this tenet leads to the passivity of the soul.

(Appaḍikamaṇaṃ duvihaṃ davvd bhave appaccakkhāṇaṃ pi) Apratikramaṇa and apratyākhyāna are of two types—physical and psychical (edeṇuvadeseṇa du cedā akārago vaṇṇido) this tenet leads to the passivity of the soul.

(Java ādā davvabhāvāṇaṃ paccakkhāṇaṃ ṇa kuvvadi) So long the soul does not practise both types [—physical as well as psychical—] of pratyākhyāna (abstinence) and so long as the soul does not perform both types [—physical and psychical—] of pratikramaṇa [confession and repentance of past deeds], (tāva du so kattā hodi ṇādavvo) it must be believed that the soul continues the bondage of karma.

(Ādhākammādῑyā je ime poggaladavvassa dosā) Ādhākarma and the like are the transgressions determined by material substance; (te ṇāṇῑ kiha kuvvadi je du ṇiccaṃ parādavvaguṇa) how can an enlightened sage perpetrate them when these are aliens?

(Imaṃ ādhākammaṃ ca uddesiyaṃ poggalamayaṃ davvaṃ) [The transgression such as] ādhākarma and auddeśika are alien material substances (jaṃ ṇiccaṃ acedaṇaṃ vuttaṃ taṃ) which are said to be eternally non-consciousness; (mama kada kiha hodi) how can they be done by me?

Annotations:

In the verses 8.47 to 8.49, the author deals with the topics of apratikramaṇa and apratyākhyāna. Pratikramaṇa means confession and repentance for past transgressions or wrong-doings. Apratikramaṇa, therefore, implies 'instead of confession and repantance, recalling to memory the past impure experiences with implicit approval'. Apratikramaṇa is of two types: physical and psychical. In the same way, pratyākhyāna means resolving for abstinence from a desire for future sensual enjoyment or any evil act. Apratyākhyāna, therefore, implies 'not to practise pratyākhyāna'. It means the absence of self-restraint, and hence, an uninhabitated longing for future sensual pleasures or evil act. It is also of two types: physical and psychical.

The dravya apratikramaṇa and dravya apratyākhyāna are the material karmic conditions responsible for the corresponding bhāva apratikramaṇa and bhāva apratyākhyāna—psychic states of emotion either approving the past impure experiences and longing for the future sensual pleasures or evil act, respectively. Both these types are related with karma, and not with the pure Self. Hence, the pure Self cannot be considered as the causal agent of both types of apratikramaṇa and apratyākhyāna.

Now, Ācārya Kundakunda says that this is the dictum of the scriptures. But when the pure Self forgets its own real nature and identifies itself with the grosser emotions of the empirical ego, he is not able to repent for the past experiences, nor refrain from the future ones. So long as he is thus spiritually incapacitated to wipe out the past and to reject the future, he feels himself responsible for all those impure emotions caused by karmic materials and thus he becomes the kartā or the causal agent of those experiences.

In the last two verses of the chapter, the author cites an example of the transgression like ādhākarma and auddeśika. These are the transgressions of the food etc. to be accepted by an ascetic. The ascetic should only accept food etc. free from these transgressions. Ādhākarma means—"A type of udgama doṣa (blemish of bhikṣā (accepting food etc. by going to houses for collecting them in conformity with the canonical instruction)) relating to origination or preparation of food etc.); after making a decision for cooking etc. oneself or making other cook etc. the food etc. (for entertaining monks), to get the food etc. (for entertaining monks) prepared."[1] Auddeśika means—"A type of udgama doṣa (blemish of bhikṣā (accepting food etc. by going to houses for collecting them in conformity with the canonical instruction)) relating to origination or preparation of food etc.); food etc., prepared for giving it as dāna (offering) to the nirgranthas (i.e., the Jain ascetics) by indulging in āraṃbha (violence) and samāraṃbha (assualt etc.)."[2]

Both the above transgressions should be avoided by the ascetic.

Now Ācārya Kundakunda cites these transgressions as an example of apratikramaṇa and apratyākhyāna. The ascetic, who knows that ādhākarma and auddeśika are both inanimate material substances and that his pure Self cannot be the perpetrator of the non-consciousness or non-self, would never accept such food infested with these transgressions. Only he can accept such food, who forgets the pure Self. The pure Self cannot be considered the kartā of such transgression.

The gist of the verses 8.47 to 8.51 is that the ascetic should always occupy himself in the concentration on pure Self, and thereby only he can remain free from apratikramaṇa, apratyākhyāna, ādhākarma and auddeśika. On the other hand, all these are committed by the ascetic who forgets the dictum of the scriptures.

It is very important that one should not misinterpret the dictum of the scriptures. When transcendentally the pure Self is not the kartā of apratikramaṇa etc., it should not be interpreted then that pratikramaṇa and pratyākhyāna are meaningless for the ascetic, or there is no harm in accepting food infested with the transgression like ādhāarma and auddeśika. The ascetic can maintain the unconcernedness and indifference of the pure Self only by the practice of pratikramaṇa and pratyākhyāna, disowning the past impure experiences and rejecting the future occurance of those impure psychic states. If, on the other hand, the Self, by abandoning the spiritual discipline imposed by pratikramaṇa and pratyākhyāna, identifies itself with the past impure emotions and readily commits himself to future similar indulgences, he becomes fully responsible for the defects thereof, and therefore gets bound by corresponding karmas. This case, is therefore analogous to the case where the person accepts the defective and impure food though he is not concerned with the preparation thereof.[3]

(Idi aṭṭhamo baṃdhādhiyāro samatto)

[Here ends the eighth chapter on Baṃdha (Bondage).]

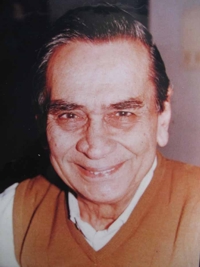

Jethalal S. Zaveri

Jethalal S. Zaveri

Prof. Muni Mahendra Kumar

Prof. Muni Mahendra Kumar