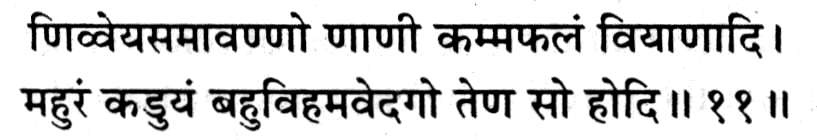

ṇivveyusamāvaṇṇo ṇāṇῑ kammaphalaṃ viyāṇadi.

mahuraṃ kaḍuyaṃ bahuvihamavedago teṇa so hodi..11

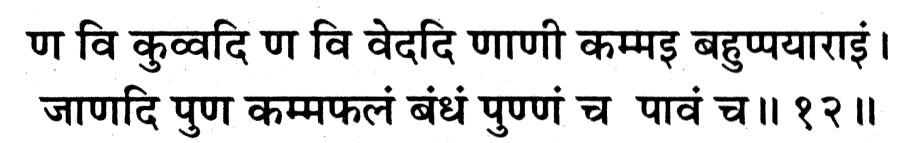

ṇa vi kuvvadi ṇa vi vedadi ṇāṇῑ kammai bahupayārāiṃ.

jāṇadi puṇa kammaphalaṃ baṃdhaṃ puṇṇaṃ ca pāvaṃ ca..12

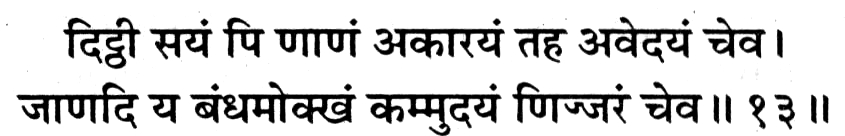

diṭṭhῑ sayaṃ pi ṇāṇaṃ akārayaṃ taha avedayaṃ ceva.

jāṇadi ya baṃdhamokkhaṃ kammudayaṃ ṇijjaraṃ ceva..13

(Ṇivveyasamāvaṇṇo ṇāṇῑ) The enlightened soul, equipped with the strength of apathy (for the sensuous pleasures of the worldly existence), (avedago hodi) does not become involved in the enjoyment of (bahuvihaṃ kammapphalaṃ) various types of fruition of karma—(mahuraṃ kaḍuyaṃ) sweet [and] bitter, (viyāṇādi) [though] he is very well aware of them.

(Nāṇi) The enlightened soul (bahuppayārāiṃ kammāi ṇa vi kuvvadi ṇa vi vedadi) neither does nor enjoys or suffers various types of karma; (puṇa) but [he] (puṇṇaṃ ca pāvaṃ ca baṃdhaṃ kammaphalaṃ jāṇadi) is fully aware of both the bondage and rise (fruition) of auspicious as well as inauspicious types of karma [i.e., he remains uninvolved in them].

[Just as] (Diṭṭhῑ sayaṃ pi akārayaṃ taha avedayaṃ ceva) the sense-organ of sight, being distinct from what it perceives, does neither brings a scene/sight into existence, nor does it enjoy it, (taha) in the same way, (ṇāṇaṃ) knowledge/consciousness, [being distinct from karma, does neither bring it into existence nor does it enjoy its fruit]; (baṃdha-mokhaṃ ya kammudayaṃ ṇijjaraṃ ceva jāṇadi) [he is] merely aware of the various stages such as bondage [bandha], fruition [udaya], partial dissociation [nirjarā] and total demolition [mokṣa] [of karma].

Annotations:

In these verses, the learned author uses the well-known fact of our experience that there is no causal relation between visual perception and the perceived object, to illustrate the function of knowledge/consciousness. The function of the sense-organ of sight is to perceive and be aware of whatever happens to come within its field of vision. But the object of perception, being distinct from the faculty of vision, is neither produced nor destroyed by it. In other words, function of the faculty is to perceive, observe, be aware of and not to create or demolish the perceived object. Hence the perceived object remains unaffected by the act of perception. Were the two causally related, then in the case of fire as an object of perception, the perceiver must burst into flame in order to produce fire perceived. But no such thing happens in reality. The function of knowledge/consciousness, says the author, is the same as the faculty of perception and the relation between it and the known object is also identical as in the case of the visual perception. That is, since there is no causal relation, knowledge cannot be regarded as producer of the objects known.

In the case of knowledge, the objects of perception/awareness are the karma. Just as an object of vision is quite distinct from the faculty of vision, so also is knowledge quite distinct from all stages and processes of karma. Thus, both—sense-organ of sight as well as knowledge—are aware, but neither producer nor enjoyer, i.e., each of them is akāraka—not a cause, and also avedaka—non-enjoyer of bondage (bandha), Rise (udaya), partial dissociation (nirjarā) and final liberation (mokṣa), which being objects of awareness, are known but not produced.

In the worldly life, a person has to enjoy or suffer various vicissitudes of life. Sometimes he enjoys the sweetness of good luck and at other times, he has to taste the bitterness of misfortune. Thus, one becomes elated with joy or is plunged in to misery depending upon his worldly state. However, an enlightened person who is well aware that pleasures and pains are the result of the fruition of auspicious or inauspicious karma respectively, remains unperturbed in both conditions. He has made himself immune to the vagaries and vicissitudes of life by insulating himself with vairāgya—apathy for worldly pleasure and suffering. While being aware of everything, nothing can make him lose his equanimity, and hence, is free from the effects of the fruition of karma—good or bad. Whenever the enlightened person passes through a favourable phase of life, he knows that it is the result of the rise and fruition of auspicious karma. At the same time, he also knows that to be elated with joy is to invite the fresh bondage of karma. Similarly, whenever he is subjected to conditions leading to grief and suffering, he knows that some inauspicious karma has come to fruition to inflict the undesirable conditions. Knowing that fruition of both auspicious and inauspicious is not only transitory but the cause of new bondage if one becomes involved in it. By remaining indifferent and aloof (being insulated with vairāgya) he avoids new bondage and gets rid of the old one.

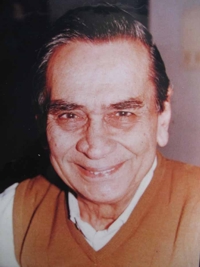

Jethalal S. Zaveri

Jethalal S. Zaveri

Prof. Muni Mahendra Kumar

Prof. Muni Mahendra Kumar