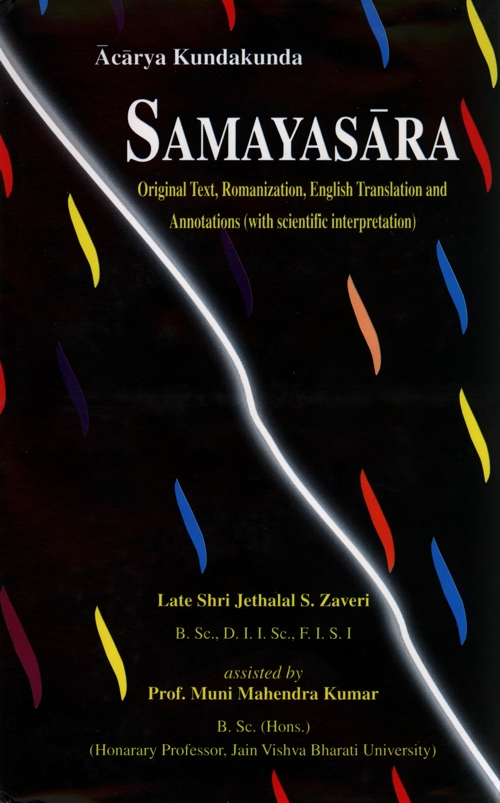

asuho suho va saddo ṇa taṃ bhaṇadi suṇasu maṃ ti so ceva.

ṇa ya edi viṇiggahiduṃ sodavisayamāgadaṃ saddaṃ..68

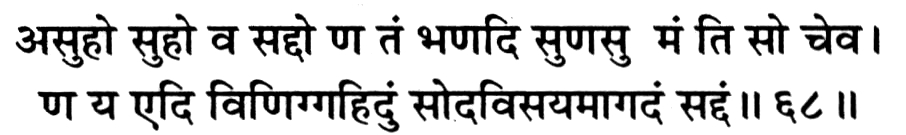

asuhaṃ suhaṃ va rūvaṃ ṇa taṃ bhaṇadi peccha maṃ ti so ceva.

ṇay a edi viṇiggahiduṃ cakkhuvisayamāgadaṃ rūvam..69

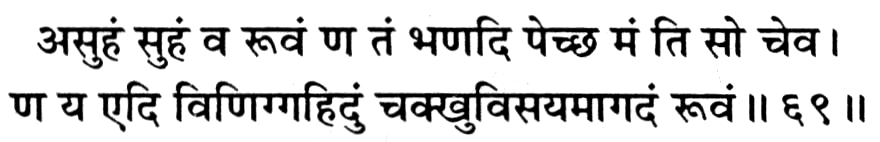

asuho suho va gaṃdho ṇa taṃ bhaṇadi jiggha maṃ ti so ceva.

ṇa ya edi viṇiggahiduṃ ghāṇavisayamāgadaṃ gaṃdhaṃ..70

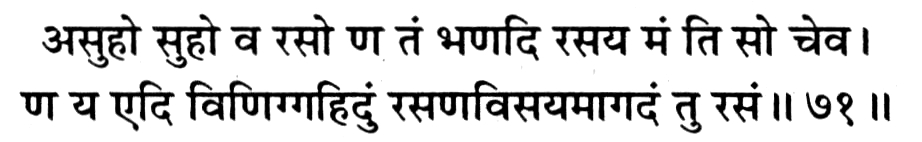

asuho suho va raso ṇa taṃ bhaṇadi rasaya maṃ ti so ceva.

ṇa ya edi viṇiggahiduṃ rasaṇavisayamāgadaṃ tu rasaṃ..71

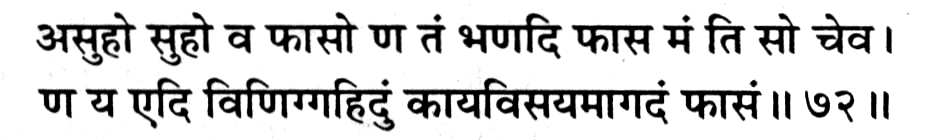

asuho suho va phāso ṇa taṃ bhaṇadi phāsa maṃ ti so ceva.

ṇa ya edi viṇiggahiduṃ kdyavisayamāgadaṃ phāsaṃ..72

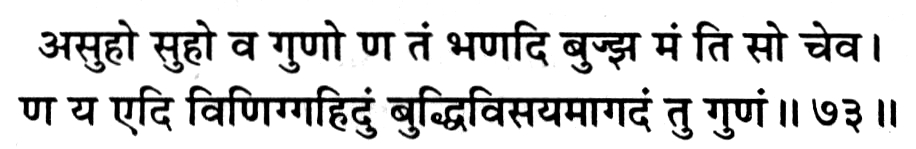

asuho suho va guṇo ṇa taṃ bhaṇadi bujjha maṃ ti so ceva.

ṇa ya edi viṇiggahiduṃ buddhivisayamāgadaṃ tu guṇaṃ..73

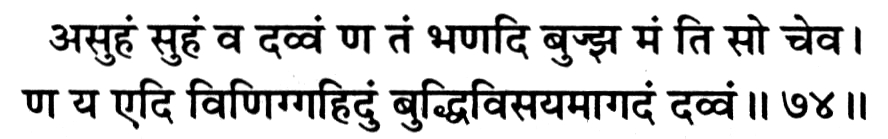

asuhaṃ suhaṃ va davvaṃ ṇa taṃ bhaṇadi bujjha maṃ ti so ceva.

ṇa ya edi viṇiggahiduṃ buddhivisayamāgadaṃ davvaṃ..74

evaṃ tu jāṇidūṇa ya uvasamaṃ ṇeva gacchade mūḍho.

ṇiggahamaṇā parassa ya sayaṃ ca buddhiṃ sivamapatto..75

(Asuho suho va saddo taṃ ti ṇa bhaṇadi maṃ suṇasu) Neither inauspicious (unpleasant) nor auspicious (pleasant) words invite you, by themselves, "hear us", (so ceva sodavisayamāgadaṃ saddaṃ viṇiggahiduṃ ṇa ya edi) and that soul also does not go [leaving its place] to apprehend the sound that has reached the organ of hearing [—even when the sound waves reach the organ of hearing, they cannot forcibly compel your faculty to perceive them].

(Asuhaṃ suhaṃ va rūvaṃ taṃ ti ṇa bhaṇadi maṃ peccha) Neither an unpleasant nor a pleasant sight, by itself, invites you "see me"; (so ceva cakkhuvisayamāgadaṃ rūvaṃ viṇiggahiduṃ ṇa ya edi) and that soul also does not go [leaving its place] to apprehend the sense-data of vision that has reached the organ of sight [—even when the sense-data of vision reaches the organ of sight, it cannot forcibly compel your faculty to perceive it].

(Asuho suho va gaṃdho taṃ ti ṇa bhaṇadi maṃ jiggha) Neither an unpleasant nor a pleasant odour, by itself, invites you "smell me"; (so ceva ghāṇāvisayamāgadaṃ gaṃdhaṃ viṇiggahiduṃ ṇa ya edi) that soul also does not go [leaving its place] to apprehend the sense-data of odour that has reached the organ of odour [—even when the sense-data of smell reaches the organ of smell, it cannot forcibly compel your faculty to perceive it].

(Asuho suho va raso taṃ ti ṇa bhaṇadi maṃ rasaya) Neither an unpleasant nor a pleasant taste, by itself, invites you "taste me"; (so ceva rasaṇavisayamāgadaṃ tu rasaṃ viṇiggahiduṃ ṇa ya edi) that soul also does not go [leaving its place] to apprehend the sense-data of touch that has reached the organ of touch [—even when the sense-data of taste reaches the organ of taste, it cannot forcibly compel your faculty to perceive it].

(Asuho suho va phāso taṃ ti ṇa bhaṇadi maṃ phāsa) Neither an unpleasant nor a pleasant touches, by itself, invites you "touch me"; (so ceva kāyavisayamāgadaṃ phāsaṃ viṇiggahiduṃ ṇa ya edi) that soul also does not go [leaving its place] to apprehend the sense-data of touch that has reached the organ of touch [—even when the sense-data of touch reaches the organ of touch, it cannot forcibly compel your faculty to perceive it].

(Asuho suho va guṇo taṃ ti ṇa bhaṇādi maṃ bujjha) Neither an unpleasant nor a pleasant quality (of a physical object), by itself, invites you "know [think of] me"; (so ceva buddhivisayamāgadaṃ tu guṇaṃ viṇiggahiduṃ ṇa ya edi) that soul also does not go [leaving its place] to apprehend the quality that has reached the instrument of thinking [even when the quality reaches the instrument of thinking, it cannot forcibly compel your faculty to perceive it.

(Asuhaṃ suhaṃ va davva taṃ ti ṇa bhaṇadi maṃ bujjha) Neither an unpleasant nor a pleasant substance (physical object), by itself, invites you "think of me" (so ceva buddhivisayamāgadaṃ davvaṃ viṇiggahidu ṇa ya edi) that soul also does not go [leaving its place] to apprehend the substance (physical object) that has reached the instrument of thinking [even when the idea of the object reaches the instrument of thinking, it cannot forcibly compel your faculty to perceive it].

(Evaṃ tu jāṇidūṇa ya mūḍho uvasamaṃ ṇeva gacchede) Thus, inspite of knowing [the nature of sound, colour, odour, taste, touch, a physical object and its qualities], the [unenlightened] deluded soul does not attain equanimity [mental happiness]; (ya parassa ṇiggahamaṇā) it craves for [does not abstain from] the external sensuous data (sayaṃ ca sivaṃ buddhiṃ apatto) because it has not yet attained the blissful faculty of [enlightenment].

Annotations:

Continuing the discussion of important doctrines, the author, in the above verses, deals with the process of perceptual knowledge of physical objects and their characteristic qualities. He shows that mental agitation results from the pleasant and unpleasant nature of these qualities only if the perceiver, the soul, chooses to involve itself and pays attention to them.

The soul, the conscious substance is the central figure on the cosmic stage of worldly life, it is completely enveloped by an inanimate or consciousless, environment. Knowledge is inherent in the soul, that is, absence of knowledge is unnatural to it even as darkness is foreign to the sun. Knowledge can emerge with or with or without the help of the sense-organs. Of the five classes of knowledge, according to the Jain epistemology, the sensuous (matijñāna) and scriptural (śrutajñāna) need the assistance of sense-organs, which are, however, only external instruments, the different states of the soul itself being the internal or spiritual counterparts of them.

The sense-organs recognized in this system are the usual five while the mind, the instrument of conception, is called a quasi-sense. Sensory awareness (sensuous cognition) is the result of the contact between a sense-organ and sense-data—colour, odour, taste etc. possessed by physical existence, that is, only the physical objects can be apprehended by sense-organs. Sensation is the result of contact between the sense-organ and the sense-data. In the case of sight, the contact is indirect while in the case of other senses there is direct contact.

Scientifically, sensation is the result of the sequence:

Stimulus→Receptor→Connecting Pathway→Sensory area in the brain.

Our body is equipped with a versatile assortment of sensory outpost which constantly receives the stimuli proceeding from the physical objects, and reaches the appropriate sense-organ. The sense-organs and other sensory outposts send millions of separate sensation signals—coded messages—in the form of nerve impulses from sensory receptors in all parts of the body to the brain, through appropriate pathways, every second. These raw sensations—the unprocessed inputs of awareness—must be processed by various parts of the brain before becoming perception. By a remarkable process of automatization,[1] a vast majority of these sensations are automatically filtered out and prevented from reaching the higher brain i.e., from becoming perception or awareness. A few are permitted through to brain region above brainstem. Of these the significant ones are sorted out from the trivial and only the essential, unusual, and dangerous ones are forwarded to the conscious mind. While a person may be partially aware of many sounds, smells or movements around him, concentration is limited to one sensation at a time.

It can be seen from the above that there is remarkable unanimity between the scientific version of the process of perception and the Jain views regarding sensuous cognition. The significant factor emphasized in the above verses is that the mere presence of the sense, stimuli and their coming into contact with the respective sense-organs is not effective enough to produce the psychic reaction in the consciousness i.e., perceptual cognition. The fundamental reason why a particular sense-stimulus is successful of becoming perception and producing the corresponding psychic reaction of pleasure or pain is because of the selective attention of the individual which itself is the result of his own interest in the perceived object. Stated differently, it is this interest in the particular physical object towards which the selective attention of the perceiver is directed that is mainly responsible for that particular perception. Whatever interests him, whether it is sound or sight or any other sense-stimulus, will be perceived by him and others will pass away unnoticed.

Thus, the causal condition of the psychic fact of perception is the perceiver's own interest, i.e., the perceiver himself and not the perceived object. The perception brought about by the selective attention of the perceiver, is followed by the hedonic reaction of pleasure of pain in the consciousness of the perceiver. And again the intensity of the pleasure or pain accompanying the psychic fact of perception vary from individual to individual, depending upon the attitude of each, though the intensity of the sense-stimuli may be identical in each case. And this is the very point that the author wants to emphasize.

The sense-stimuli pertaining to sound, sight, smell, taste and touch, proceeding from the external environment, are entirely physical in nature and hence cannot be directly responsible for the psychic modification, both perceptual and hedonic, produced in the individual soul. Both these psychic modification are entirely determined by the psychological attitude of the soul. Thus, to hold the physical existence and it characteristic qualities to be responsible for the hedonic reaction of the soul is mere ignorance of the philosophical as well as scientific truths. Addressing an unenlightened person who is ignorant of the total inability of the sense-stimuli to produce perception and the hedonic reaction, the author exhorts him to refrain from being angry and unhappy.

The prescription for maintaining equanimity—mental peace and happiness is extremely simple, once the facts about the process of perception is known. One should simply stop taking interest in the physical world and ignore the sense-stimuli which manage to cross the threshold of consciousness and try to produce a psychic reaction. By itself, not even the strongest stimuli can compel the soul to produce a perceptual modification, let alone a hedonic one. All that is needed is to fully engage the machinery of perceptual cognition in self-perception and get absorbed in perceiving infinite glory of the pure self. Those who become angry on hearing the words of censure must learn and realize that words are nothing but a peculiar combination of the material molecules of bhāṣā vargaṇā, and they may succeed in reaching your sense-organ of hearing but they are absolutely powerless to produce either a perceptual or a hedonic modification, unless you yourself permit them to do so. Nothing in the vast environment of physical existence, abounding in sense-stimuli of various types is capable of disturbing you from self-perception, by themselves. And remember that the highest sensuous pleasure is utterly insignificant compared to the spiritual bliss resulting from self-perception.

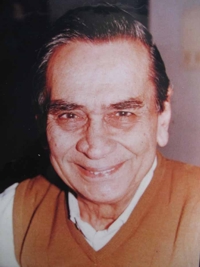

Jethalal S. Zaveri

Jethalal S. Zaveri

Prof. Muni Mahendra Kumar

Prof. Muni Mahendra Kumar