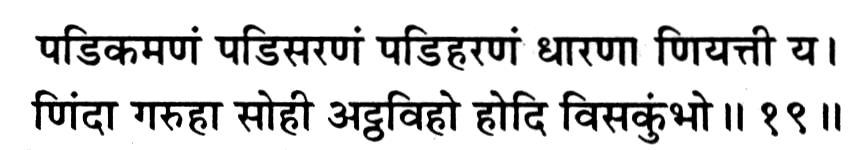

paḍikamaṇaṃ paḍisaraṇaṃ paḍiharaṇaṃ dhāraṇā ṇiyattῑ ya.

ṇiṃdā garuhā sohῑ aṭṭhaviho hodi visakuṃbho.. 19

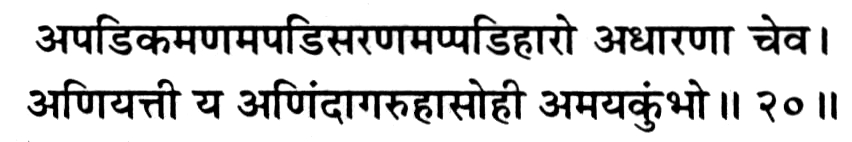

apaḍikamaṇamapaḍisaraṇamappaḍihāro adhāraṇā ceva.

aṇiyattῑ ya aṇiṃādgaruhāsohῑ amayakuṃbho.. 20

(Paḍikamaṇaṃ) Repentance for past transgression [pratikramaṇa], (paḍisaraṇaṃ) pursuit of the benevolent [pratisaraṇaṃ] (parihāra) abandoning the evil [parihāra] (dhāraṇā) deep concentration, (ṇiyatti) renunciation of material objects [nivṛtti], (nimdā) self-deprecation [nindā], (garuhā) act of confessing one's transgression before the guru [garhā], (sohῑ) expiation for purification [śuddhi]—(aṭṭhaviho visakuṃbho hodi) these are the eight pots of poison.

(Apaḍikamaṇa) Non-repentance for past transgressions, (apratikramaṇa), (apaḍisaraṇa) non-pursuit of the benevolent, (aparihāro) non-abandunce of the evil (aparihāra), (adhāraṇā) non-concentration, (aṇiyaṭṭi ya) non-renunciation of material objects [aṇivṛtti], (aṇiṃdā) non-self-deprecation [anindā], (ceva agaruhāsohῑ) non-confession before the guru [agarhā] and non-expiation for purification [aśuddhi]—these are the eight pots of nectar.

Annotations:

In the preceding verses, the author had emphasized that the soul is able to become totally free from guilt and fear, if it only adores/idolizes its own purest state. Now in the concluding verse of this chapter, he deals with eight kinds of moral discipline, which are traditionally and conventionally recognized as formula for freeing the soul from the guilt complex. Traditionally, they are prescribed to be practised by all devout aspirants for controlling one's emotions and passions and their regular practice is generally recognized as essential for spiritual advancement/progress. The learned author, however, apparently rejects the traditional belief and calls eight acts of discipline—'eight pots of poison' and the opposites of these acts are called—'pots of nectar'. Thus, on the face of it, the two verses are diametrically opposite to the teaching of scriptures as traditionally believed and practised and may be considered shockingly heretical by many.

It is, however, totally inconceivable that an erudite scholar of scriptures and a staunch devotee of omniscient (Jinendra Deva), like Ācārya Kundakunda, can ever negate a practice prescribed in the scriptures. We must, therefore, reject the apparent meaning of the verses and try to seek and find the proper meaning which is commensurate with the teaching of the scriptures. But, firstly let us briefly discuss these eight types of discipline which constitute, empirically, the formula for becoming free from guilt.

- Pratikramaṇa—literally means retracing one's steps, i.e. act of mental retraction and repentance for transgressions already committed, either deliberately or inadvertently. It is incumbent as a daily performance for all religious people, both ascetic and laity.

- Pratisaraṇa—is the act for further strengthening/reinforcing the purity of the soul by inculcation right faith and belief. It also includes relevant vows for the future.

- Parihāra—is the act of rejecting the evil by freeing the soul from perverted belief, attachment and the like, which corrupt the soul and keeps it bound to the wheel of the cycles of rebirths.

- Dhāraṇā—act of deliberate mental exercise whereby the wandering mind is steadied by the help of external props such as recitation of spells, worshiping of idols, canalization of thought etc..

- Nivṛtti—act of mental freedom from gross passions. The mind is ever hankering for sensuous pleasures and carnal desires. By this act it is controlled and trained to desist from wandering into the fields which nourish the worldly state.

- Nindā—act of self-deprecation for past errors. This is associated with the act of pratikramaṇa, i.e., retraction from transgressions. One must, first, recognize an error as a misdeed and then self-deprecate it.

- Garhā—act of confession to an elder, generally the Ācārya. This is complementary to no. 6 above. While niṇda is self-confession, garhā is confession in the presence of an elder.

- Śuddhi—act of purifying the soul by expiation. This is the final step in the series of daily routine. The guru after hearing the disciple's confession, directs him to undertake specific expiatory actions which purify the soul from the transgression.

It can be easily seen that all the above mentioned acts are religious acts and from empirical aspect, well established ones for purifying the soul and rendering it free from the guilt of transgressions—deliberate or accidental. Why, then, does the author emphasize on the self-adoration as the only means for removing the guilt complex and at the same time brand the traditional acts as pots of poison?

Throughout the book, the learned author has depicted the empirical aspect as inferior to the transcendental one, though he has justified its adoption at appropriate stages of spiritual progress. In the above verses, the author presents a very advanced stage of spiritual purity, where the necessity for empirical disciplines are already over. What is a pot of nectar for the developing stage where empirical acts are necessary for further advancement, could be regarded as a pot of poison as such acts might degrade rather than advance the purity of the soul. Moreover from the transcendental aspect all acts and the desire for being an actor/doer (rather than a seer) are obstacles in the path of final liberation. All the eight acts enumerated in these verses are valid up to a certain stage of spiritual purification, but since, they are dependent on external props, they must be renounced and abandoned as non-self in favour of self-meditation. It should be remembered, however, that while renouncement of empirical religious acts of discipline is prescribed at the highest level of self-purification, they are, positively essential and must be practised diligently during the earlier immature stages.

(Idi ṇavamo mokkhādhiyāro samatto)

[Here ends the ninth chapter on Mokṣa (SeIf-realization)/Total Liberation.]

Jethalal S. Zaveri

Jethalal S. Zaveri

Prof. Muni Mahendra Kumar

Prof. Muni Mahendra Kumar