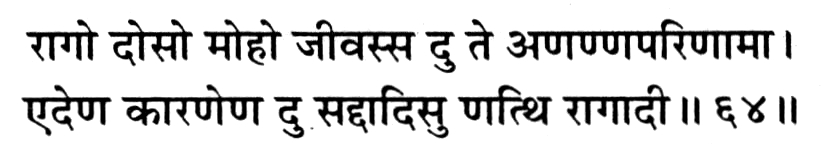

rāgo doso moho jῑvassa du te aṇaṇṇapariṇāmā.

edeṇa kāraṇeṇa du saddādisu ṇatthi rāgādi..64

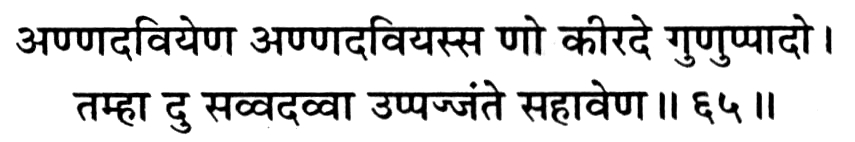

aṇṇadaviyeṇa aṇṇadaviyassa ṇo kῑrade guṇuppādo.

tamhā du savvadavvā uppajjaṃte sahāveṇa..65

(Rāgo doso moho te jῑvassa du aṇaṇṇapariṇāmā) The psychic states—attachment, aversion, and delusion—are the soul's own attributes [before enlightenment] (edeṇa kāraṇeṇa du rāgādῑ saddādisu ṇatthi) and that is why the sound etc. [which are the characteristics of the physical existence] do not possess attachment and the like.

(Aṇṇadaviyeṇa aṇṇadaviyassa guṇuppādo ṇo kῑrade) A substance can never produce qualities/attributes of another substance, [according to the metaphysical law]; (tamhā du savvadavvā sahāveṇa uppajjaṃte) that is why each substance produces its own qualities/attributes which are possessed by that substance only.

Annotations:

In these verses, the author initiates the discussion on some fundamental metaphysical laws relating to the qualities modes/states and their substratum the substance. This discussion is further continued in the succeeding verse up to 10.75.

According to the law of anekānta, a substance is a continuum through the infinite variations of its modes at every moment of its existence. The eternal continuity of the substance is as much a reality as the variations. Thus, there is unity as well as multiplicity in perfect harmony. Again, the admission of existence of a substance involves the existence of qualities and modes—jointly called attributes—possessed by it. For "to say that something exists inevitably raises the question what this something is. And that question must be answered by asserting something of it other than its existence." "It remains true that something exists, but of that something, something besides its existence must be true. Now that which is true of something is a quality of that something. And therefore whatever is existent must have some quality besides existence which is itself a quality."[1]

"If we deny the possession of quality, the existent/substance is an absolute blank and to say that only this exists is equivalent to saying that nothing exists."[2] And the admission of quality involves the admission of a relation between the quality and the substance to which the quality belongs. And again, the existence of other substances which is asserted by perception cannot be denied. "Unless it is the case either that solipsism is true, or that I myself have no reality, it must be the case that both I and something else exist."[3]

And this would prove that there is a plurality of substances. "All substances will be similar to one another for they are all substances, and they will be diverse from one another, since they are separate substances. And substances which are similar to each other or diverse from one another, stand to each other in the relations of similarity and diversity."[4]

And again if there were no relation between a quality and substance or between a substance and its modes, quality and modes would be unreal, as they cannot exist independently of and apart from a substance to which they belong. A mode which is not a mode of anything and a quality which is not a quality of anything, is neither a mode nor a quality. And a quality which is not a quality is nothing. But if modes and qualities are unreal, substance, too, cannot be real. Thus, the denial of concrete relations between a substance and a quality makes them unreal fictions. On the other hand, with concrete relations, a substance and its attributes are so closely bound together that destruction of one would lead to the destruction of the other. But when the relation is superficial and not intrinsic, the destruction of one need not follow the other's destruction. For example, in the case of an object placed on a table, destruction of one does not necessarily follow the destruction of the other.

According to another law of anekānta, there is a total absence of characteristic qualities of one substance in another. Thus, consciousness is the characteristic of the soul, and therefore, it can never be possessed by physical substance—matter. We have seen that consciousness is split into three factors—belief, knowledge and conduct—from the empirical aspect. Therefore, these are totally absent in the physical existent in any form—material objects, karma, and physical bodies of the living organisms. The attributes of the soul are superficially related to karmic matter and karma. Realization of the pure nature of the soul necessarily presupposes the destruction of the impure states of the consciousness—perverted faith, knowledge and conduct—and during its spiritual advancement the soul destroys the perverted knowledge etc., but the destruction of the soul's own modes has no effect on the physical substance, because the psychic attributes of the soul have nothing to do with the physical existence. The impure emotional states of attachment, aversion and perversion which emanated from delusion will disappear and the soul will attain its pure state with the destruction of delusion. Quoting this law, the author reminds us that, nowhere in the scriptures, there is any indication of destroying the karmic matter. The term demolition of karma for attaining final liberation does not mean destruction of karmic matter and if one believes that the soul has to destroy karmic matter to become enlightened he is very much mistaken. What is destroyed is perversion and delusion which are soul's own impure states, in order to produce right faith, right knowledge and right conduct. The nature of the physical existence is incapable of accommodating the impurity and the restoration of purity of consciousness.

Yet another important metaphysical law lays down that every substance is the material cause of its own modes and no other substance is capable of producing them and transferring them on to the substance to which they belong. The modes of a substance are identical with it because the substance itself is focused in the modes. They are not absolutely different from substance as in that case they would not belong to the substance; for example, clay is transformed into ajar and so the former is regarded as the cause of the latter. The jar is, no doubt, different from clay, but the jar could not be ajar unless it was the same substance as clay. The mode and the substance may, thus, be viewed as identical and also as different, as they are both in one. A mode and a substance are different because they are two and they are identical because one is not absolutely independent of the other. The absolutist way of looking at things leads to the affirmation of one and to the negation of the other. The error is the result of the habit of the absolutist philosophers to put the telescope on the blind eye and then to assert that the other aspect is not real. The law of anekānta voices the necessity of using both the eyes and of seeing the obverse and the reverse of the coin of reality.

The author, thus, emphasizes the fact that psychic states of attachment and aversion can never be produced by the physical existence—karmic matter etc.. Hence, if a person who sincerely desires for spiritual advancement, considers the physical objects, karmic matter, karma, and his physical body, to be the cause of his own impure state and thinks of destroying them, he merely exhibits his ignorance of the metaphysical laws and achieves nothing.

Jethalal S. Zaveri

Jethalal S. Zaveri

Prof. Muni Mahendra Kumar

Prof. Muni Mahendra Kumar